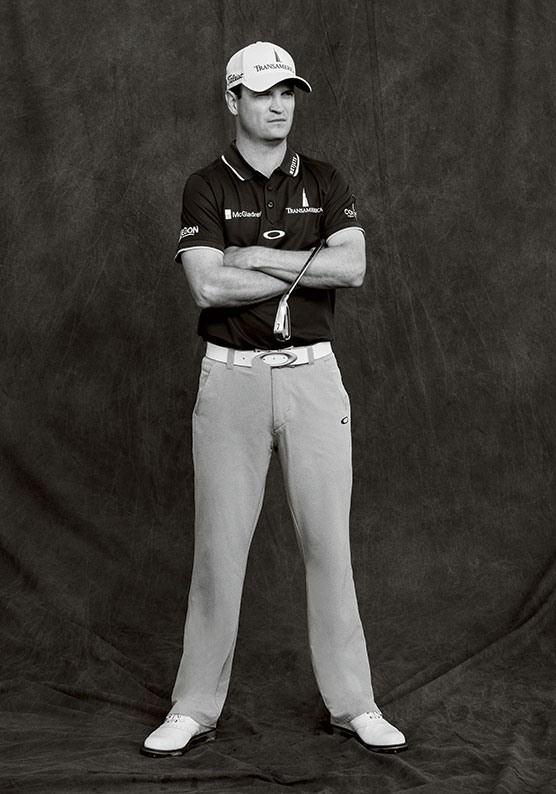

It might be hard for everyone still mourning Jordan Spieth’s lost Grand Slam to hear, but Zach Johnson isn’t boring. Without the shades he wears on the course to protect light-sensitive eyes, his boyish features emerge as tender and tough; half (actor) Joaquin Phoenix, half middleweight. And liberated from the intentional flatlining he effects in competition, he’s an engaged live wire who moves when he talks. The little guy known for little ball definitely gives off a surprising physical presence. Part of it might be the afterglow of winning a British Open on the Old Course last year, but he’s also getting bigger, physically.

Under a program designed by his chiropractor and trainer, Troy Van Biezen, who also works with Spieth and Rickie Fowler, Johnson, 39, is striving to gain 5 kilograms of muscle that would bring him to 80kg on a small-boned, 5-foot-11 frame. Most days, Johnson does 30-minute high-intensity workouts that blast the legs and glutes, and he gulps two protein shakes to go with three big meals. “The older I get, the more I like the gym,” he says.

Johnson’s younger sister, Maria J. Drees, by acclamation the best natural athlete in the family (a 400-metre sprinter) and who Zach acknowledges is still “ripped,” cheerfully concedes her big brother has made up ground. “You can see a muscle in his back now when he swings,” she says. “He’s getting bigger and looking better. Zach is catching up.”

It’s the story of his life, though public credit has been in short supply. The buzz kill that many felt at St Andrews was reminiscent of a similar reaction when Johnson won at Augusta in 2007. “I get it,” Johnson says. “People wanted Tiger to win then. People wanted Jordan to win this year.” Even in the four-hole playoff, the crowd favourite was Louis Oosthuizen, the South African with a breathtaking golf swing.

It doesn’t bother Johnson. He knows he’s colourless on the course. “I like to play what I call a-motional golf,” he says. “Emotion doesn’t grab me that much.” In small groups, he has a disarming and winning way of playing off his image. “How are my eight hairs looking?” he asks a video technician before an interview, patting his thin dome. His clean, self-aware performance reading David Letterman’s Top-10 List after the 2007 Masters win included deadpanning the line, “Even

I have never heard of me.”

Of course, modesty is mandatory for Iowans. Johnson’s father, Dave, a Cedar Rapids chiropractor, says knowingly, “Everyone in the state would be disappointed if Zach handled his success any differently.”

Surely, though, Johnson would like a little more recognition. “Not one bit,” says Kim, his wife of 12 years and mother of their three children (who admits she does wish he got more credit). “He doesn’t care. At all.” Adds Zach: “I don’t know anything different. I still feel most people don’t give me much of a chance. I don’t mind that.”

Numbers That Outdo The Competition

If Johnson has a chip on his shoulder, it’s well concealed under the long-sleeve synthetic compression shirts he often wears. He knows he can let the breadth of his consistency over 12 US PGA Tour seasons speak for itself. Before this season, Johnson could take pride in having only one bad year (2008, in which he failed to qualify for the Ryder Cup while trying too hard to live up to his Masters victory) and missing the elite field in the season-ending Tour Championship only three times. But the claret jug has changed all that. Zach Johnson from Cedar Rapids has joined Sam Snead, Jack Nicklaus, Seve Ballesteros, Nick Faldo and Tiger Woods as the only players to win the Masters and the British Open at St Andrews. And having two Major wins makes Johnson eligible to be nominated for the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Still, the fact remains that Johnson has long been better than he has looked, and better than several more-celebrated peers. Since 2004, when as a rookie Johnson won his first US PGA Tour event, his 12 official victories are exceeded by only Woods, Phil Mickelson and Vijay Singh. And since Johnson’s 2007 victory at the Masters, only Woods (23) and Mickelson (12) have more than Johnson’s 11 tour titles (the same number as Rory McIlroy).

It’s a road forged by sport. Dave Johnson told his three children, “Winning isn’t everything. But wanting to win is.” The mantra took. From primary school on, his eldest son played every team sport, along with tennis and golf. In high school, Zach played soccer, golf and basketball. He remains adept at all of them, and on a ski trip a few years ago that included some tour players he earned the nickname Double Black Zach. “Table tennis, basketball – whatever – you have to play really good to beat him,” says his longtime swing coach and friend, Mike Bender. “Zach doesn’t beat himself.”

Bender, who used to race go-carts, took a group of players and instructors to a track in San Diego with regular race cars a few years ago. “It was loser pays for dinner,” he said. “Zach had never really driven, and in the first race, I actually lapped him. But then he watched and figured out some things, like never touching the brakes, and by the last race he posted the fastest lap time. That’s the kind of competitive mind he has.”

A 44kg Freshman

Like his father, an avid athlete, Johnson’s physical maturity began later than most of his peers, and he weighed only 44kg as a freshman at Regis High School. “I had good skills, but my lack of size and speed kept me a little behind the best kids in the other sports,” Johnson says. “Golf offered a more level field. I would have rather played other sports, but golf picked me.”

Once chosen, Johnson committed to the path as if it were pre-ordained. Says his mother, Julie, who holds a master’s in education from the University of Iowa: “Zach is an oldest child who is the product of two oldest children. I don’t think he had a choice but to excel at something. He really fits that profile.”

It helped that the “clutch gene” was also prevalent in the Johnson household. “Having to step up to the plate and perform in sports, our whole family loves that sort of stuff,” says his sister. “We love watching others have the chance, but we really love to get the chance ourselves. It came from our dad, who always made it all right if we failed. We just liked that challenge and that feeling of doing something under pressure, especially Zach.”

The appeal has only grown. “I can’t wrap my brain around not wanting to be in those situations – having to execute under command,” he says. “I enjoy duress-filled situations. I enjoy nervous-type situations. I enjoy crunch-time situations.”

Certainly his early pro career was one. Johnson was never the best golfer on his high school team. He received one Division I scholarship offer, to Drake, where in four years he never made first-team All-Missouri Valley. He never excelled on the amateur circuit and didn’t come close to making a Walker Cup team. So after graduating with a bachelor of business management and marketing in 1998, his decision to turn pro the next year naturally worried his mother, among others.

But Johnson got some backing from a local group of businessmen. When he began to work with the Orlando-based Bender in late 1999, Johnson found his footing.

In 2001, he won the last three Hooters Tour events to briefly become known as Back-to-Back-to-Back Zach. After winning twice on the (then named) Nationwide Tour in 2003, he earned his US PGA Tour card and quickly won the BellSouth Classic.

Veterans could tell the scrawny short hitter had the right stuff. At the 2006 Ryder Cup in Ireland, Johnson, partnered with Scott Verplank in a four-ball match against Henrik Stenson and Padraig Harrington. On a cold, wet, blustery day, as the rest of the US team struggled, Johnson made seven birdies in a 2-and-1 victory.

“Our team that year didn’t have a whole lot of confidence,” says Verplank, “but Zach and I did. He’s a pretty good example of your mind being stronger than your body. That was the best Zach had ever played in his life to that point. He just believed he was going to do great things, with nobody else understanding why he would think that. “I guess we’re kindred spirits,” Verplank says. “When we see each other, we give this goofy little fist pump to the heart that we did in Ireland. But we look each other in the eye when we do it, and it’s like, Yeah, that’s who we are.”

But as much inner fire as Johnson exhibits on the course, he still likes other sports better. International football matches dominate his big screen at home in Georgia, especially those with his favourite player, FC Barcelona’s Lionel Messi. (“The ball on his foot, I swear there’s glue on it,” Johnson says.) As for golf, “I don’t know if I love the game – more like, I really like it,” he says. “But I love competing, and golf is my outlet to do so.”

Building Improvement

To be ultra-competitive, Johnson has mastered the art of steady improvement. “The key is always looking for the positives in every experience,” he says. “When you play bad, the positive is that you know what you need to work on.”

The framework of how to work on it was supplied by Bender, whose guidance provided the most important turning point in Johnson’s career, and who remains his coach. To create a motion that would better complement Johnson’s strong grip, Bender flattened Johnson’s swing plane and taught him to square the club more with body rotation, almost eliminating hand rotation.

His swing is notable for the way Johnson “holds off” the club turning over through the hitting area and the pronounced extension of the shaft toward the target line.

“Zach has the longest left arm through the ball I’ve ever seen,” says instructor Jim McLean. “Longer than Hogan’s.”

Adds prominent tour guru Peter Cowen: “He’s probably got more constants than anybody, and that’s what the game’s all about. The more constants you have, the more consistency you have.”

“A lot of tournament golf is controlling fear,” says Johnson’s caddie since 2004, Damon Green, who has won more than 70 mini-tour events as a player. “But Zach is just one of those guys who isn’t scared. You can’t say that about a lot of players. When he bogeyed 17 in the last round [at St Andrews] after he missed that 3-wood from the fairway so bad, I knew he wasn’t rattled. We got up on 18 tee, and I said, ‘Let’s just do what we do.’ And he did.”

As longtime tour caddie Steve Williams said last year, “Some players can’t be intimidated. Zach Johnson is at the top of that list. He knows his game, its strengths and limitations, and he trusts it. There isn’t a person or situation that is going to make him play beyond his capabilities or take risks he shouldn’t take. In fact, he’ll embrace who he is even more and relish the challenge of beating someone with a bigger game.”

Adds Green: “We were in the locker room before the last round, and Zach was looking at the scores, and he said, ‘Man, there’s a lot of guys who could win this.’ And I said, ‘No, there’s not, Zach. Most of those guys don’t have the stomach to win this. You do. At St Andrews, you got to have guts.’ ”

Since the initial changes, Bender and Johnson’s work has been mostly refinement. “We work on weaknesses,” Bender says, “but make sure his strengths stay strong.”

Those strengths are obvious. Johnson is one of the best at getting his driver in play, perennially in the top 10 on the US PGA Tour in driving accuracy. It’s imperative to his success, because his measured average clubhead speed of 173 km/h in 2015 is the second-slowest of any regular US PGA Tour player among the top-100 players in the world. (His average driving distance of 260m this year ranks 160th on tour.) To carry a ball 246m, Johnson says he has to make perfect contact.

Turning Short Into Long

But as long as he is playing from short grass, Johnson feels he can neutralise his inherent disadvantage. “If you put me in the fairway at my average distance into a par 4, 160–165m, and you put another player in the rough 110m from the green,” he says, “over time, I’m going to wear him out.”

Conversely, because he is so straight, Johnson is able to hit a driver more frequently than his longer-hitting peers, who often drop down to a 3-wood or hybrid off the tee on more narrow fairways. So there are many holes where Johnson has the longest tee shot in his group.

Second, Johnson is a virtuoso with the wedges. He has used them to achieve some iconic moments. The first

was winning the Masters without ever going for a par 5 in two, yet making birdies on 11 of those 16 holes over four rounds. The second was on the 72nd hole of the 2013 Northwestern Mutual World Challenge at Sherwood Country Club, where he defeated Woods, the tournament host. To get into a playoff, Johnson – after badly flaring an 8-iron approach into a water hazard – holed a perfectly struck 60-degree wedge from 52m that drew a memorably pained smile from Woods. “If I hit a bad shot, it’s like my focus goes up,” Johnson says. “It’s almost like a trigger.”

You could make the case that he won at St Andrews with his wedges, which he used for approaches on the Old Course’s seven par 4s under 365m and other holes as well, birdieing the 18th in every round. “It settled me down to remember how many wedges I would have on that course,” he says. “That’s when I know I can do some work.” Indeed, the same principles of limited clubhead rotation in the hitting area and long extension through the ball are more suited to wielding a wedge than with any other club.

Johnson’s key shot inside 115m is a low draw, which facilitates better contact, ball flight and distance control. Bender also likes to point out that for a right-hander who draws his wedges, pin-high shots will generally end up slightly right of the pin, which on greens that slope back to front, will leave right-to-left breaking putts – the easiest putts to hole.

Although he’s known for making big putts like the 25-footer on the 72nd hole at St Andrews that got him into the playoff, Johnson says he’s overrated as a putter, contending, “I’m probably a better ball-striker.” He points out that when he won the Masters, he three-putted six times, and he has only occasionally finished a season among the statistical leaders. But he doesn’t disagree that he seems to be better the more it matters. “I’m not a bad putter,” he says. “Maybe in certain situations that are difficult, maybe I’m better.”

The main thing is that Johnson believes in his overall game, especially under pressure. He seizes chances. In nine of his 12 victories, he has come from behind in the last round to win. “My boring, mundane, diligent kind of golf works sometimes,” he says. “Actually, it works all the time. And sometimes on the greatest stages, it really does flourish.”

Major Margin Of Error

But capturing Major championships will always be a particularly difficult challenge for Johnson. His short driving distance, low ball flight and relatively low-spin iron play make it difficult to stop his approaches near the hole when greens are firmest and fastest. Despite having won two Majors, his record in Grand Slam events is otherwise poor. In 12 US Opens, Johnson’s best finish is T30, and he has missed five cuts. In 46 Majors overall, he has eight top-10s and 15 missed cuts. Says Dr Mo Pickens, the sport psychologist Johnson has worked with since 2006: “Can Zach compete at any Major? Yes, he can. Is his margin of error smaller than Dustin Johnson’s or Jason Day’s? Yes, it is. He has to be more on than they are. But he’s getting very good at being on. One of his greatest strengths is to not be overwhelmed by the moment and keep hitting shots and putts while setting the emotions to the side,” Pickens says. “Under pressure, he can get out of his body the same things that he can get when he’s not under pressure. That’s a hard skill to acquire. As far as the guys I’ve worked with, he can do it more consistently than anybody else. He might miss a shot, but it’s not because he flinched at impact.”

Why does Johnson flinch so seldom? In his mind, the biggest reason is a perspective born of his faith. Raised a Catholic, Johnson became a committed Christian before marrying Kim in 2003. “For me, my faith has given me a new level of peace,” he says.

“Because whatever is supposed to happen is going to happen, and I’m going to be OK regardless. What takes the pressure off is this: If I can glorify God, regardless of what I shoot, it’s a good day.”To some, that might make Zach Johnson seem boring. But as he proved at the Old Course, and as he has demonstrated since boyhood to anyone who paid attention, the way he keeps catching up is exciting.

THE BOOK ON ZACH

US PGA TOUR WINS, EARNINGS

12

two in 2007, 2009, 2012;

one in 2004, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2014, 2015

Career earnings

$37.4 million

BEST FINISHES BY MAJOR

Masters

won (2007)

T9 (2015)

US Open

T30 (2011)

British Open

won (2015)

T6 (2013)

T9 (2012)

PGA Championship

T3 (2010)

T8 (2013)

T10 (2009)

RYDER CUP

2006

1-2-1 overall

0-1-0 singles

0-1-1 foursomes

1-0-0 four-balls

2010

2-1-0 overall

1-0-0 singles

1-1-0 foursomes

0-0-0 four-balls

2012

3-1-0 overall

1-0-0 singles

2-0-0 foursomes

0-1-0 four-balls

2014

0-2-1 overall

0-0-1 singles

0-2-0 foursomes

0-0-0 four-balls

Totals

6-6-2 overall

2-1-1 singles

3-4-1 foursomes

1-1-0 four-balls