The story of the Kirkwoods – Australian golf’s greatest father-and-son duo.

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree in Australian sport. Our nation’s history is full of inspiring stories of sons emulating their fathers’ successes. Think of rugby league’s Josh and Brett Morris following in their premiership-winning father Steve’s footsteps; the Marsh family in cricket; Bill Roycroft and his sons riding at the Olympics; Lindsay and Andrew Gaze in basketball; Billy and Peter Cook in horse racing; Tony and Anthony Mundine in the ring; the Abletts in the AFL. Fred Cavill, known across Australia in the late 19th century as the ‘professor of swimming’, was the father of six exceptional swimmers and the grandfather of Dick Eve, an Olympic gold-medal winning diver.

Golf, you’d think, would offer more opportunities for sons to follow champion fathers than most sports. Sons of exceptional golfers should have access to good courses, free tuition, decent clubs (even if they are ‘hand-me-downs’), maybe even understanding mums who realise homework isn’t as important as another 30 minutes practising on the putting green.

But based on the history of professional golf, it doesn’t seem to work that way. Today in the US, there is Jay and Bill Haas, Craig and Kevin Stadler, and a few years ago there was Al and Brent Geiberger. For Australia, there is really only the Kirkwoods: Joe and Joe Jr. We do, of course, have Lindy and Mathew Goggin, but son following mum isn’t quite the same thing.

Ironically, given how history has panned out, the early British Opens were dominated by two father-and-son duos. ‘Old’ Tom Morris won four Opens between 1861 and 1867. ‘Young’ Tom Morris won four straight between 1868 and 1872 (no tournament in 1871). Willie Park Sr won the inaugural championship in 1860, and won further titles in 1863, 1866 and 1875. His son won in 1887 and 1889. No son of a Major champion has won a Major since.

The closest this has come to happening since was Jack Burke, second to Ted Ray in the 1920 US Open, and his son, Jack Burke Jr, the Masters and PGA champion in 1956.

The two Stadlers were in the field at the 2014 Masters, with Kevin finishing a tie for eighth and Craig missing the cut. Sixteen years earlier, the Geibergers played in the 1998 PGA Championship. In England, Percy Alliss had 10 top-10 finishes without a win in the British Open between 1922 and 1939. His son Peter also had several top 10 Open finishes before becoming the ‘voice of golf’ in Britain. Both men played in the Ryder Cup, as did Spain’s Antonio and Ignacio Garrido (in 1979 and 1997, respectively).

Old and Young Tom would have to be regarded as world golf’s greatest father-and-son combo. Old Tom helped design some of Scotland’s most famous courses, including Prestwick, Carnoustie and Muirfield. Young Tom hit the Open Championship’s first hole-in-one and was the first man to get his name inscribed on the Claret Jug, which was introduced to the Open in 1872. The father was conservative by nature, while his son was fearless and good enough to win the Open by 11 strokes in 1869 and 12 in 1870 (the Open record remains the 13-shot margin achieved by his father in 1862). Young Tom’s death at age 24, following the death of his wife and baby in childbirth, is one of golf’s most heartbreaking tragedies. Old Tom would spend the rest of his life retelling stories about the greatest golfer he ever saw…

His son.

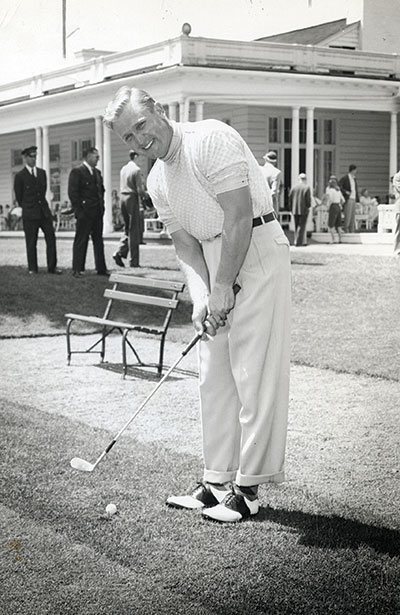

The story of the Kirkwoods is much happier. Born in Sydney in 1897, Joe Sr won the Australian Open in 1920 with a four-round total of 290, 12 strokes better than any previous total at the championship. The Australasian’s golf correspondent described the victory as “the finest exhibition of the game that has ever been witnessed in the Southern Hemisphere.” The following year, Kirkwood sailed to Britain, where he finished in a tie for sixth at the Open Championship at St Andrews, a final-round 79 ruining his prospects after he was just one shot off the lead after 54 holes. He finished six shots behind Jock Hutchison, the first US-based golfer to win the Open. Two years later, Kirkwood seemed certain to win at Troon, but instead produced the worst collapse by a contending Australian golfer in the history of the Majors, even worse than Greg Norman at the 1996 Masters.

On the final day, the local hope Arthur Havers had the clubhouse lead, but word spread that Kirkwood was playing brilliantly. As the young Australian stood on the short 14th tee he knew that if he played his final five holes in even fours he’d win by three. Instead, he went from bunker to bunker at 14, missed a short bogey putt at 15, duck-hooked his tee shot and then found the burn at 16, took three at the short 17th and then missed another short putt at 18 to finish in a tie for fourth.

Having played the back nine in 33 strokes in the third round, he played those cruel last five holes in 26 strokes. “He is essentially a card and pencil fiend who walks stealthily round the course offering threes and fours,” London’s Daily Telegraph gently observed. “But confronted by an opponent in the flesh he is sometimes less machine-like.”

Kirkwood himself might have agreed. In 1934, he explained to the legendary American sport writer Grantland Rice, “An Open championship is something different. The prize at stake … the rushing galleries … the mental and physical strain … I guess we are all human.”

The collapse at the 1923 Open left scars. Kirkwood would continue to build a reputation as, to quote the leading British golf writer Henry Leach, “a wizard with golf balls,” but his attention turned away from Major championships. He’d win 13 times in the US, most famously at the 1923 Illinois Open – when he holed his second shot from a fairway bunker at the par-4 last to beat Hutchison – but seemed more concerned with making a dollar, any best way he could.

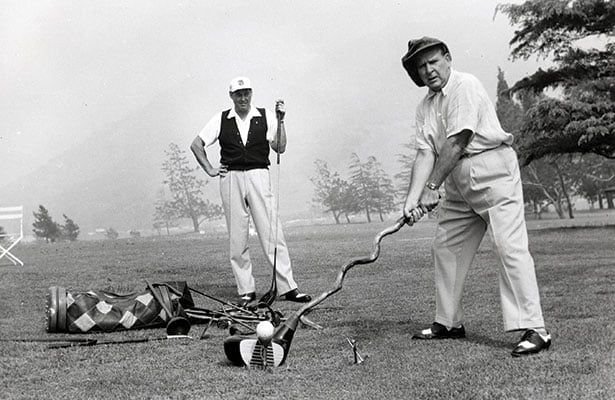

He was renowned as the master of the trick shot, a skill he developed as young pro at the Riversdale Club in Melbourne during the years of the Great War, when he found himself entertaining wounded soldiers at a nearby military hospital. P.C. Pulver, a leading golf writer and editor in the US, believed Kirkwood was “unrivalled in the variety of shots at his command.” Henry Leach rated him a “genius of the first order.” In 1921, Sporting Life magazine reported an exhibition in London: “One of his most remarkable feats was playing a niblick shot with so much back spin that he was able to catch the ball in his outstretched hand without departing from his original stance. Another interesting shot was his playing of an ordinary right-handed iron club in left-handed fashion, the result being that he played the ball with the extreme end of the back of the club, and in this case he got a goodly distance.

“Some amusement was caused by Kirkwood’s driving a ball from off the toe of the shoe of J.V. East, his business manager. One of his cleverest tricks was teeing a ball in the ordinary way, teeing a second on top of that, and in turn teeing a third, so as to make a column of three balls. He took his club in hand in the ordinary way, and, to the astonishment of the onlookers, drove the middle ball without touching either of the others, the uppermost one merely rolling peacefully on to the ground.”

A crowd favourite was to borrow a wristwatch from a spectator and then play a crisp iron shot without damaging the timepiece. When he did finally crack a watch face, it made the papers. The lucky fan had already been compensated with a much better watch than the one just broken. Kirkwood toured the US and the world, including trips to Asia, Africa and Australia with champions such as Walter Hagen and Gene Sarazen, combining trick-shot shows with exhibition rounds in front of big galleries. He still played tournament golf, winning a Canadian Open in 1933, finishing T4 at the 1927 British Open and reaching the semi-finals of the 1930 US PGA Championship. At age 49, he finished T8 at the 1946 British Open. “Why should I?” He replied one day when asked if he should be concentrating more on big tournaments. “The trick shots are more valuable to me than a championship would be.”

The stuff of legend

KIRKWOOD built a bank of amazing stories, like the one that happened in Mexia, Texas, when he set out on an exhibition round and then noticed everyone in the gallery was riding a horse. No one was walking. He waited until after the round was over before asking questions.

“What’s the idea with you fellows going around the course on horseback?”

“I’ll tell you, Joe,” said one hospitable local. “It’s all on account of our president dying after playing a round yesterday. He got bit by a rattlesnake. The whole place is thick with ’em. We’re just glad none of ’em bit you.”

As a teaching professional, he was in high demand, counting presidents and prime ministers, dukes and maharajahs among his admirers. He also passed on some of his genius to his son, Joe Kirkwood Jr, who was born in Melbourne just a few months before his father’s Australian Open triumph. In 1940, Joe Jr took up a position as an assistant golf professional at the Capital City Country Club in Atlanta, the start of a career in golf that would see him win three times on the US PGA Tour.

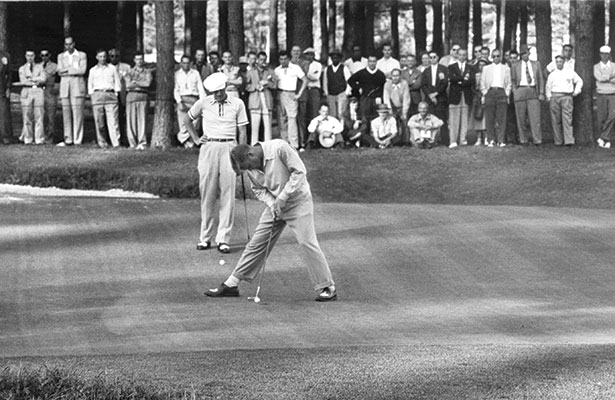

His most notable win came in 1951, at the rich Blue Ribbon Open in Milwaukee, when he stormed past Sam Snead, Jim Ferrier and Lloyd Mangrum with a final-round 64. Rice wrote that Joe Jr had one of the best swings he’d ever seen. At the 1948 US Open, both Kirkwoods made the cut, a feat matched 56 years later by Jay and Bill Haas.

Joe Jr achieved this while fighting a paternity suit (it was alleged he was the father of twins), and also establishing himself as a genuine TV and movie star. In 1945, he did a screen test for the role of Joe Palooka, the main character in a comic strip about an American heavyweight, got the part, and went on to star in a series of Joe Palooka films. In 1949, he enjoyed a stage tour with a young Marilyn Monroe. He was later a high-profile radio and TV celebrity. Today, you can find Joe Jr’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Both men died in the US: Joe in 1970; Joe Jr in 2006. The senior Kirkwood must be remembered as the man who put Australian golf on the world map, and as one of our very greatest: not far behind Peter Thomson and Greg Norman; up there with Jim Ferrier, Kel Nagle and Adam Scott. He remained a proud Australian – “I’m still an Aussie. Look, here’s my passport,” he shouted to reporters when he returned to Sydney in 1954 – and Joe Jr was very much his father’s son. The winner of the Australian PGA Championship is presented with the Joe Kirkwood Cup.

They might not have built records in Majors to match Young and Old Tom Morris, and for all their achievements you couldn’t rank the Kirkwoods as Australia’s No.1 sporting family.

But this Father’s Day let’s remember them as our best father-and-son team. Golf has not produced another pair quite like them. And likely never will.