Last Friday at The Greenbrier, on his final hole, Kevin Chappell had an 11-foot birdie putt to shoot the second 58 in PGA Tour history. The first came from Jim Furyk, at the 2016 Travelers Championship, and that round put him in extremely rare professional company – only Ryo Ishikawa, on the Japan Golf Tour, and Stephan Jaeger, on what was then the Web.com Tour, shot 58s on major professional tours. Head down to the minors, and you’ll find an Irishman named David Carey who shot a 57 this year on the Alps Tour. And in the amateur ranks, college golfer Alex Ross shot a 57 at the Dogwood Invitational in June.

As for the lowest ever, that honour goes to Australian PGA Tour player Rhein Gibson, who shot 55 in a private round in Oklahoma. (Homero Blancas shot the same score in a college tournament, but it was discounted by the Guinness Book of World Records for happening on a course that was too short.)

Back to Chappell. He actually didn’t make that final putt, and golf immortality slipped from his grasp. He still shot 59, which represents its own irrefutable place in history, but he missed his chance to stake a claim for the best round of all time on the PGA Tour. Or did he?

It’s time to ask the big, hard question: what’s the best way to determine the G.O.A.T. round? And who shot it?

The truth is, the concept of judging “the greatest round” is not as simple as a cumulative number. The most obvious complication of that approach is that not all golf courses are created equal. Shooting a 59 at Oakmont, for instance, would be relatively more impressive than doing it at Old White TPC, which is now the first PGA Tour course to have witnessed two 59s after Aussie Stuart Appleby did it there in 2010. And yet, there’s no fair way to sort for “course difficulty”, because it varies day to day due to weather and setup.

Another method for solving this riddle is to ignore the 18-hole total and simply look at score relative to par. By that metric, four golfers have shot 13-under on the PGA Tour: Al Geiberger, Chip Beck, David Duval and Adam Hadwin. Each shot 59, meaning they pulled off the feat at a par-72 course. Isn’t it fair to say that shooting 59 on a par 72 is better than shooting the same score on a par 70?

Unfortunately for those of us who like easy answers, the answer is “probably not”.

Stay with me here: most par-72 courses have four par 5s, and statistics show that, especially in the modern game, par 5s are the easiest holes to birdie, and the only holes that offer a non-fluky opportunity for eagle. So while “par” is higher, the course itself is technically “easier” because of those par 5s. A professional golfer on a par-72 course has more chances to make birdies and eagles, and thus improve his score relative to par, than the same golfer on a par 70. In plain English, that means the “extra” birdies or eagles made by the players who shot 13-under are offset by their good luck in playing a par 72. Considering that, it’s no coincidence that the only 13-unders have come on par-72 courses – it’s actually an easier feat. (Credit goes to the AP’s Doug Ferguson for patiently explaining this to me years ago.)

Remember Carey’s 57 on the Alps Tour? That was on a par 68, which reads as less impressive at first glance. But what it actually means is that he made 11 birdies on par 3 or par 4 holes. Compare that to David Duval’s famous 59 at the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic in 1999, where he made a par, two birdies and one eagle on the par 5s, meaning he played the par 3 and par 4 holes in nine-under for the day. Can you really say, based on those numbers, that one round was more impressive than the other?

Thus far, we’ve ignored other elements, such as situational pressure (Duval shot his 59 on a Sunday) or history (for whatever reason, it’s easier to shoot 59 today… there were just three 59s on the PGA Tour before 2000, but there have been eight in the past decade). But the one factor we can’t ignore, and that helps us view each 58 or 59 in its proper context, is the performance of the rest of the field. It has a way of cutting through the clutter; comparing each superlative round with the average play of the entire field accounts for course difficulty, weather and even score relative to par. It boils everything down to a simple, all-encompassing question: how much better were you, on a given day, than your peers?

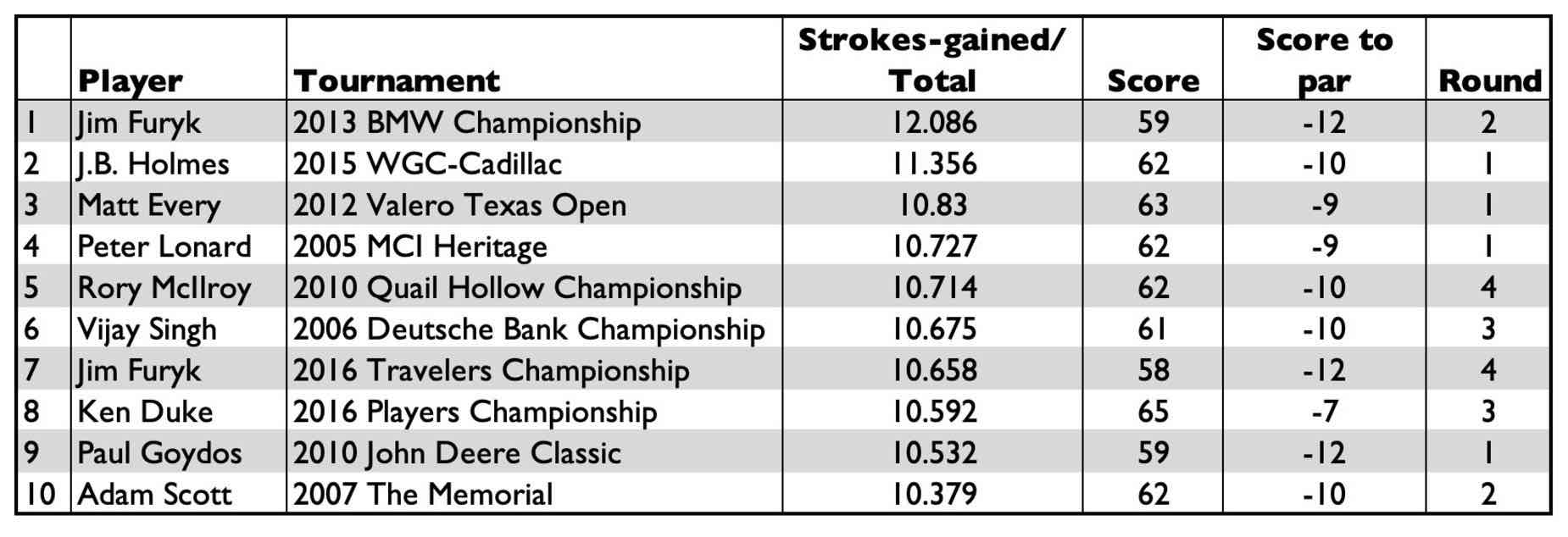

Luckily, we have a stat for that, and that stat is ‘strokes gained’. With thanks to Tom Alter, Luis Rivera and the ShotLink crew at the PGA Tour, we now know the top-10 individual rounds, by strokes gained, since these stats were first kept in 2004:

As you see, score alone doesn’t define the best round. Ken Duke, who ranks eighth on the list, shot “only” a 65 on Saturday at the 2016 Players Championship. But TPC Sawgrass was so difficult that day (players compared the greens to Shinnecock Hills, with an average field score of 75.6, that Duke’s performance ranks among the greatest rounds of the past 15 years. And then there’s Rory McIlroy, who closed with a 62 to beat the course average by 10 strokes to win the 2010 Quail Hollow Championship for the fifth-best round since strokes gained was recorded.

Meanwhile, Chappell’s 59 doesn’t crack the top 10 or even the top 25; it ranked 26th according to the tour. (For what it’s worth, he would likely have put up the No.3 SG round if he’d made his 58.)

The best of the best goes to Jim Furyk, and it’s not for his famous 58 – that ranks seventh. It’s for his lone career 59, a feat he managed at the 2013 BMW Championship. The average score that day at Conway Farms outside Chicago was 71.1, and Furyk’s SG number was 12.086, the best day by that metric since 2004.

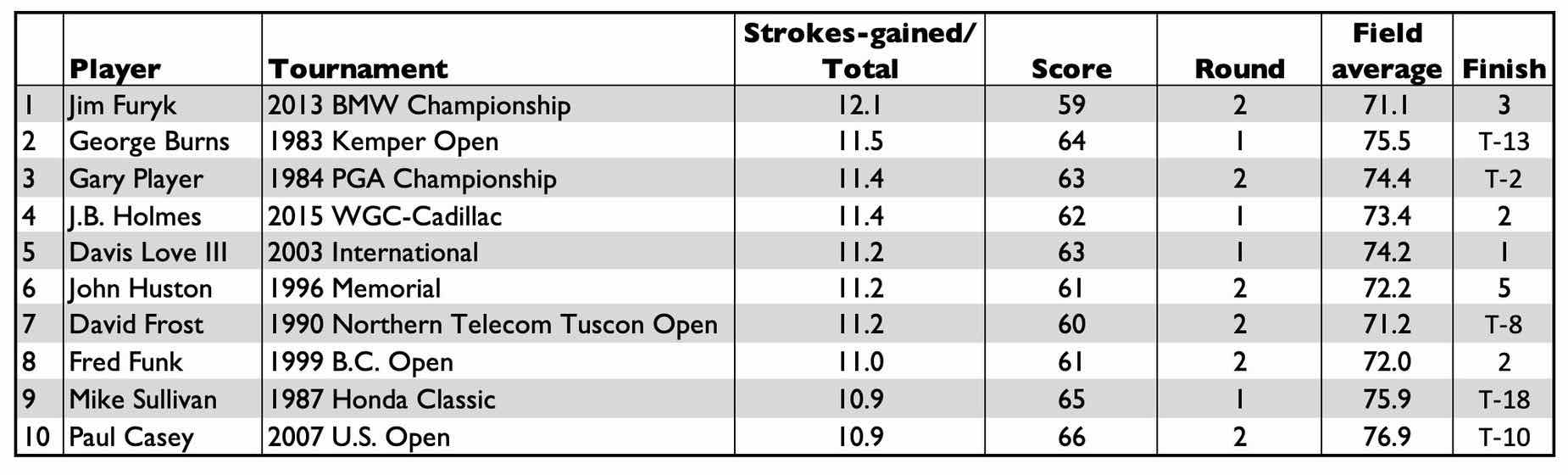

But what about before 2004? For that question, we turn to Mark Broadie, who I have previously described, and will again, as “Columbia Business School professor and golf statistics guru/pioneer/virtuoso”. He was able to send me the top 10 SG individual rounds since 1983:

Two interesting facts: first, every player on that list shot his historic round in the first or second round. (Could that be because more players post higher scores on those days, allowing for a higher SG number before the worst are winnowed by the cut?) Second, Jim Furyk’s 2013 BMW round is still the best, at least of the past 37 years.

And now for one last nitpick: is strokes gained really the perfect metric? Could it be skewed by certain players having really bad rounds on a day when someone else excelled? When Furyk shot his 59 at the BMW, for instance, there were only 70 players in the field, and a few of them, including Rory and Patrick Reed, shot 76 or worse. With a full field, would that SG number have been quite as high?

Maybe! But maybe not. My point is, although strokes gained is a terrific tool for answering this question, there’s still room for interpretation. So let me finish this column with my opinion: Rory McIlroy’s Sunday 62 at the 2010 Quail Hollow Championship represents the highest SG total in a final round at least since 2004, and it gave him the comeback victory over the likes of Phil Mickelson, Rickie Fowler and Jim Furyk. Even better, it was Rory’s first win on the PGA Tour. When you consider the stats and the circumstances, and acknowledging the limitations of our pre-1983 knowledge, that was the greatest single round in PGA Tour history.

Surely, this will be the most controversial award Rory wins this year.