How a fearless and insatiably curious second-year pro from Norway developed his swing using the internet.

In a year when golf (and the world) was knocked sideways by a pandemic, a guy who gained 20 kilograms in four months broke the US Open with 200 miles per hour of ball speed, the woman who won the AIG Open Championship couldn’t get into the next LPGA Major and arguably the greatest player of all time waited seven extra months to defend his Masters title on an empty, dormant Augusta National then later mangled a car and possibly the rest of his career in a road accident, can you really say any story is, well, surprising?

Still, Viktor Hovland would like to have a word. The second-year pro from Norway has been on a run. A member of the celebrated 2019 class that includes Oklahoma State University teammate Matthew Wolff and PGA Championship winner Collin Morikawa, Hovland validated his formidable college credentials – the 2018 US Amateur and NCAA team titles and low-amateur finishes at the 2019 Masters and US Open – with two PGA Tour wins in his first year as a professional. Both of them came in dramatic fashion. In February 2020 at the Puerto Rico Open, Hovland made a 30-footer for birdie on the last hole to beat Josh Teater. In December, he made a 12-footer in Mexico to best Aaron Wise.

‘He treated his swing like lego, tinkering, adding and subtracting’

Even the disarray imposed on the tour schedule could not push Hovland off path. He bought an anonymous McMansion halfway between the Oklahoma State campus and Karsten Creek, the team’s home course, and did pretty much what he has done since he was a 12-year-old swing nerd who had 18 hours of daily Norwegian winter darkness to fill. He watched movies, listened to music and devoured countless hours of online golf instruction and treated his swing like Lego, tinkering, adding and subtracting while using the directions as a reference, not a blueprint.

Hovland, 23, has to be the first elite tour player to teach himself the game from scratch in the dark in a second language from YouTube. He’s just one of a wave of new tour players who are using the most democratic of the modern instruction tools – social media – to redefine the relationship between athletes, coaches and the information they share.

It’s the new way to get good.

A chubby, short kid

One of the traditional ways tour players have gotten good is to play for a blue-chip program like Oklahoma State. OSU has produced a lot of them, from Bob Tway and Scott Verplank to Charles Howell III and Rickie Fowler – players who helped the program win 11 national titles in the USA.

Those titles require talent, and Cowboys coach Alan Bratton was in Scotland at the European Boys Team Championship in 2013 to fill the pool. His main target on the Norwegian team was Kristoffer Ventura, a 6-foot-3 specimen equipped with a tour-player starter set of skills who would end up playing four years at OSU.

But Bratton couldn’t stop watching a chubby, 5-foot-6 kid with an untucked shirt and Oakley blade sunglasses who came from the same high school in Oslo as Ventura. “Viktor was a little soft and had a different-looking swing, but that swing repeated, and I loved how he competed,” Bratton says. “He might have been only the fourth or fifth best player on that team, but I fell in love with him. I’ve been fortunate to be around a lot of great players, and I thought I saw some of the same traits in him. When I was recruiting Rickie Fowler, I had a plan to watch him and then watch other people, but I couldn’t stop watching Rickie. It’s rare to see him frustrated. He tries shots, and he’s fun to watch. Viktor is the same way.”

That Hovland was even swinging a golf club as a high schooler was an act of providence. His father, Harald, had spent a year as a visiting engineer on a project in St Louis and had bought some clubs during that stretch to kill time at a practice range that was on his way to work. When the year was up, he brought a junior set of clubs back to Norway for his son to try, and by age 11, Viktor was committed.

The Hovlands entrusted Viktor’s embryonic game to James McGowan, a transplanted Australian who has been teaching at Norway’s Drobak Golf Club for more than two decades. From the start, Hovland’s thirst for information and work ethic set him apart. “The first player from Norway to make it to the PGA Tour, Henrik Bjornstad, was a member here when Viktor was a junior. I coached Henrik, too, and he didn’t work as hard as Viktor did,” says McGowan, who taught Hovland from ages 11 to 17. “In the summer, it stays light until 10:30, and even then, Viktor’s parents spent a lot of time waiting in the carpark for him to finish.”

‘In the summer, it stays light in Norway until 10:30, and even then, Viktor’s parents spent a lot of time waiting in the carpark for him to finish’

The flipside of those endless summer nights is about six hours of daylight in the winter. That translated into hundreds of hours of web surfing and beating balls at the Fornebu Indoor Golf Centre – and Hovland interrogating McGowan about everything from the latest swing trends on tour to his TrackMan numbers. “I didn’t have one myself at the time,” McGowan says, “but Viktor had a TrackMan at school he could use, so he would work on the numbers to see if what we talked about worked.” The Stack-and-Tilt method was strong on the tour at that time, but Hovland bypassed it without a second glance, preferring to work on adding some Dustin Johnson lead-wrist flavour to his swing to produce more power. “He just kept improving, and there were no flat spots on the way,” McGowan says. “Viktor’s only weakness was putting from around 10 feet, which was the birdie length he mostly had. If he had made more of that length, he would have gone extremely low much more often.”

Hovland’s growth coincided with a massive proliferation of digital-golf coaching personalities across every platform from Instagram to Twitter to YouTube to Facebook. George Gankas parlayed his social-media reach – including quarter-of-a-million followers on Instagram – into real-world work with tour players like Wolff and a spot on Golf Digest’s 50 Best Teachers list. The UK-based teaching pair of Andy Proudman and Piers Ward have more than 700,000 subscribers for their “Me and My Golf” YouTube channel, and they offer everything from a $19 monthly content-streaming membership to pre-packaged $100 “Break 90” video series. They are just some of the brands in that game. Do a search for how to fix your slice, and YouTube will offer up more than 1.1 million videos.

Hovland was comfortable with that world from the start, and he learned quickly how not to drink from the information firehose. “I started young getting into the golf swing, so I feel I have a pretty good understanding of what’s going on and how it relates to what I’m doing when I hit a ball,” Hovland says. “There’s the valuable stuff, and the stuff you hear and throw out, and then there’s the grey area in between, where you don’t really know. You try it out and see how it goes and leave yourself some breadcrumbs so that you can get back to where you were.” In its best form, that meant taking lots of trips to the golf-information buffet – where grip-adjustment tips from tour legends are mixed with recorded lectures from sports scientists about the importance of understanding moment of inertia.

But by the time Hovland was in his second year at Oklahoma State, in 2017, his variables were varying, and he was having trouble digesting the remote coaching he was getting from Denny Lucas, a Florida-based coach he had found through Instagram. Hovland’s ball flight had flattened to where he was having trouble holding greens with longer clubs. Legendary OSU coach Mike Holder might have sent Bratton the player out to hit a few more buckets of practice balls during Bratton’s All-American senior year in 1995, but Bratton the coach had to take a 21st-century approach. “We felt like he wasn’t understanding something the coach was telling him remotely,” Bratton says. “So over the Thanksgiving break, he went to see the coach in Jupiter. That helped him get it, and when he came back, he had all this height. He built momentum from there and really hasn’t looked back. I just love the way he plays – confident, not afraid.”

Instant success on tour

That fear element – or the lack of it – is what makes players like Hovland, Wolff, Morikawa and Bryson DeChambeau so different. They came on tour ready to win because they had seen their peers do it. DeChambeau was runner-up in the Australian Masters as an amateur in 2015 and tied for fourth in Hilton Head in his 2016 professional debut. Wolff won the 2019 NCAA individual championship in May and on the PGA Tour in July. The next month, in starts four, five and six, Morikawa went T-2, T-4 and won. Hovland finished 12th as an amateur in the 2019 US Open and was a millionaire before he pegged it up for the first time

as a professional the next week, at the 2019 Travelers Championship, thanks

to an equipment deal with Ping.

“Look at what Wolff did over those few weeks in 2019,” Bratton says. “Turning pro didn’t make him any better or make him a different player. He was capable as an amateur. It’s a matter of telling a player the truth about the skill set you need to play at a given level, establishing an environment where they can do that, and then free them to understand for themselves that they can win.”

The step into professional golf only reinforced the same drive in Hovland that had transformed his body from chunky to chiselled and validated the personal experiments he conducts on his swing. “There are always things to improve, and I have always liked to work,” Hovland says. “But I think a strength for me is the ability to say, Yeah, something might be a valuable piece of information for somebody, but it’s not necessarily for me. I’m not vulnerable to going to somebody and just giving my brain to them. I want to learn things for myself.”

Hovland’s experience winning in Puerto Rico paid in more ways than just the $US540,000 cheque. He dumped two chips on the 11th hole on Sunday, leading to a triple-bogey and laying bare the realisation he shared with everybody in the interview after saving the day with his putter. “I suck at chipping,” he said, with his widest trademark smile. “That’s something I know I’m going to have to improve if I want to play my best at this level.”

For Bratton, Hovland’s openness and willingness to judge his game unemotionally make him a virtual unicorn in professional golf. “I love his honesty – and the confidence to be honest. To say, ‘I suck at chipping’? No tour player will make himself that vulnerable,” says Bratton, who caddied for Hovland at the 2018 US Amateur and 2019 Masters and US Open. “The first European Tour event Viktor played in, he did that double-pump, top-of-the-backswing thing he does in a real round. My phone blew up with people sending me clips of it, so I called him and said, ‘What are you doing? When did you start that?’ He said, ‘This morning.’ He did it as a drill, and it felt good, so he put it in.

It was the same thing at the US Open. He had pretty much the best driving week anybody has ever had. The next week, in Hartford, he was trying the double-pump thing on a couple of holes. The confidence to do that shows who he is.”

Hovland addressed his short-game shortcoming head-on. Before the COVID quarantine hit, Hovland worked early in tournament weeks with legendary coach Pete Cowen – who helped Brooks Koepka and Gary Woodland with their short games – on using the bounce on his

wedges more effectively. By sliding the club instead of digging it, Hovland could control the loft on his shots more precisely, and the club was less prone to dig the way it did in Puerto Rico.

The work – and the enforced downtime when the tour shut down last March – gave Hovland time he says was reminiscent of when he was 12 years old, when it was all about playing golf for fun and looking for answers online. The hunt led him to some of the online material created by Jeff Smith, a Las Vegas-based instructor who works with several young tour players, such as Aaron Wise and Patrick Rodgers, at TPC Summerlin. Smith and Hovland had mutual friends, so Hovland was comfortable reaching out to ask if Smith would be willing to look at some video of his swing.

“He was on a fact-finding mission,” Smith says. “What were the different views of his swing? What could he take away? Viktor has a high IQ related to golf, golf instruction and swing mechanics. He’s always thinking. He’s a highly intellectual individual. He doesn’t show

it off by downloading information onto you, but he can tell really quickly when something passes the sniff test or not.”

‘I called him and said, ‘what are you doing? when did you start that?’ he said, ‘this morning.’ he did it as a drill, and it felt good, so he put it in’

Smith described what he thought were the elements of Hovland’s swing that worked together to produce his elite ball-striking and told Hovland that he didn’t think he needed to make any big changes. “It was more about helping him understand his tendencies and why they showed up when they did and doing problem-solving,” Smith says. “When a certain shot pattern shows up on the course, how do you clear that up?”

In typical Hovland style, student and coach met up live for the first time in Boston before the first round of the FedEx Cup playoffs because, hey, there’s no time like the present. “Viktor’s generation of players, they want to know,” says Smith, whose Instagram account has become

a popular analytical storehouse for millennial swings on the PGA Tour. “You present them with the information, and they take it and decipher it and make the determination about what to do with it. The previous generation believed you dug it out of the dirt, and you knew it when you felt it. The problem is that you could spend the rest of your career trying to find what you had again.”

The two did not do much in terms of technical changes, but what they did do is work on doing the same things at a faster rate. “There was a lot for me to gain just by deciding to swing harder,” Hovland says. “So I spend a segment of practice time just swinging the club as hard as I can.”

Smith says the truth is that Hovland might not have much room to improve his elite ball-striking, so increased speed, by default, is where it’s at. “You give Viktor a 7, 8, 9-iron, and it’s right on the flag. Now the idea is get a 7-iron in your hand where you used to have a 5-iron. He’s been sending me videos where he’s swinging 120 miles per hour.”

Hovland’s driver speed last year, 113 miles per hour, put him 109th in that category, slower than players like Kevin Na and Lucas Glover. Ramping it up to 120 would put Hovland near the top 20, among players like Brooks Koepka and Dustin Johnson. Mix 15 more metres off the tee with Hovland’s top-10 ranking in strokes gained on approach shots, and it’s easy to speculate about the closeness of the race between Hovland and Wolff to be the next OSU graduate to win a Major.

At home in Oklahoma

Experiencing the close-knit Oklahoma State golf fraternity even for a day makes it easy to understand why Hovland wasn’t tempted to spend his money to relocate in Orlando, Jupiter, Dallas or one of the other popular tour-player hot spots in America. The team facility at Karsten Creek is built with the connective tissue of players going back to the earliest days of the program, in the form of memorabilia, donations and time – the stream of players returning for pro-am fundraisers and for no reason beyond shooting the breeze with players to pass on some institutional knowledge.

Hovland’s comfort level in Oklahoma is obvious, and a house is one of the few things he has spent his tournament earnings on. If you didn’t know who he was, you would think he was still a student. When Hovland was enrolled, he rented a room from teammate Austin Eckroat’s parents, who had bought a place so that they could keep an eye on their son from nearby Edmond. Now Eckroat lives at Hovland’s place, and for most of the COVID shutdown, they lived golf’s version of “Groundhog Day”.

“Viktor was already the most boring person, so it wasn’t a big change: work out, eat, go to Karsten, come home and watch a war movie,” says Eckroat, who is playing his senior year for OSU and getting ready for a pro career. “It was weird to be playing all that golf without having something to prepare for. Viktor never stopped working. I’ve never seen anyone hit so many balls. You go out with him, and it doesn’t feel like anything he’s doing blows you away, but the ball always stays in front of him. He’s just relentless.”

Outside golf, Hovland used his time to experiment with different diets, intermittently fasting before settling on a routine that is a mix between professional athlete and recent college student: take-away from Panera Bread interspersed with two giant fruit smoothies and a never-ending bowl of popcorn. Despite his Scandinavian roots, Hovland doesn’t drink like a European. “Once in a blue moon, he’ll go out, and that’s one of the best nights, but after a drink or two he’s a total liability,” says Eckroat, inserting the needle. “But he can go out and be himself and nobody bothers him. He gets recognised, but in Stillwater, people mind their own business. It’s simple, stress free.”

Hovland says he feels a duty to Bratton and the team to pass on his experience and advice just like Howell, Fowler and Peter Uihlein have. For his part, Eckroat is the only college senior in the USA who has two of his best friends in the top 15 of the world ranking. The week of Hovland’s win in Mexico. Eckroat got a spot in the tournament because of his ranking in the PGA Tour University standings – a system designed to provide a path for top college players to transition seamlessly to the Korn Ferry Tour. While Hovland was on his way to winning, Eckroat tied for 12th. “They had a party on the beach after the tournament, and Viktor was just as happy for me as I was for him,” Eckroat says. “That’s the guy he is. You watch him work so hard, and he shows you that you can do it, and he [cheers] for you to get there with your own hard work.”

The joy Hovland gets from immersing himself in the process of improvement was one of the first things that drew Bratton to him. “The second time I saw him, he had a different grip, and he had changed his shot shape from a hard hook to a little cut,” Bratton says. “It was obvious he had put a huge amount of time into getting better. Guys like Viktor and Bryson try their thing while continuing to be themselves. They’re sculpting their games more than building them. You have to decide who you are and own that. At the elite level, that means being yourself every day.”

Check your lead wrist to slice-proof your swing

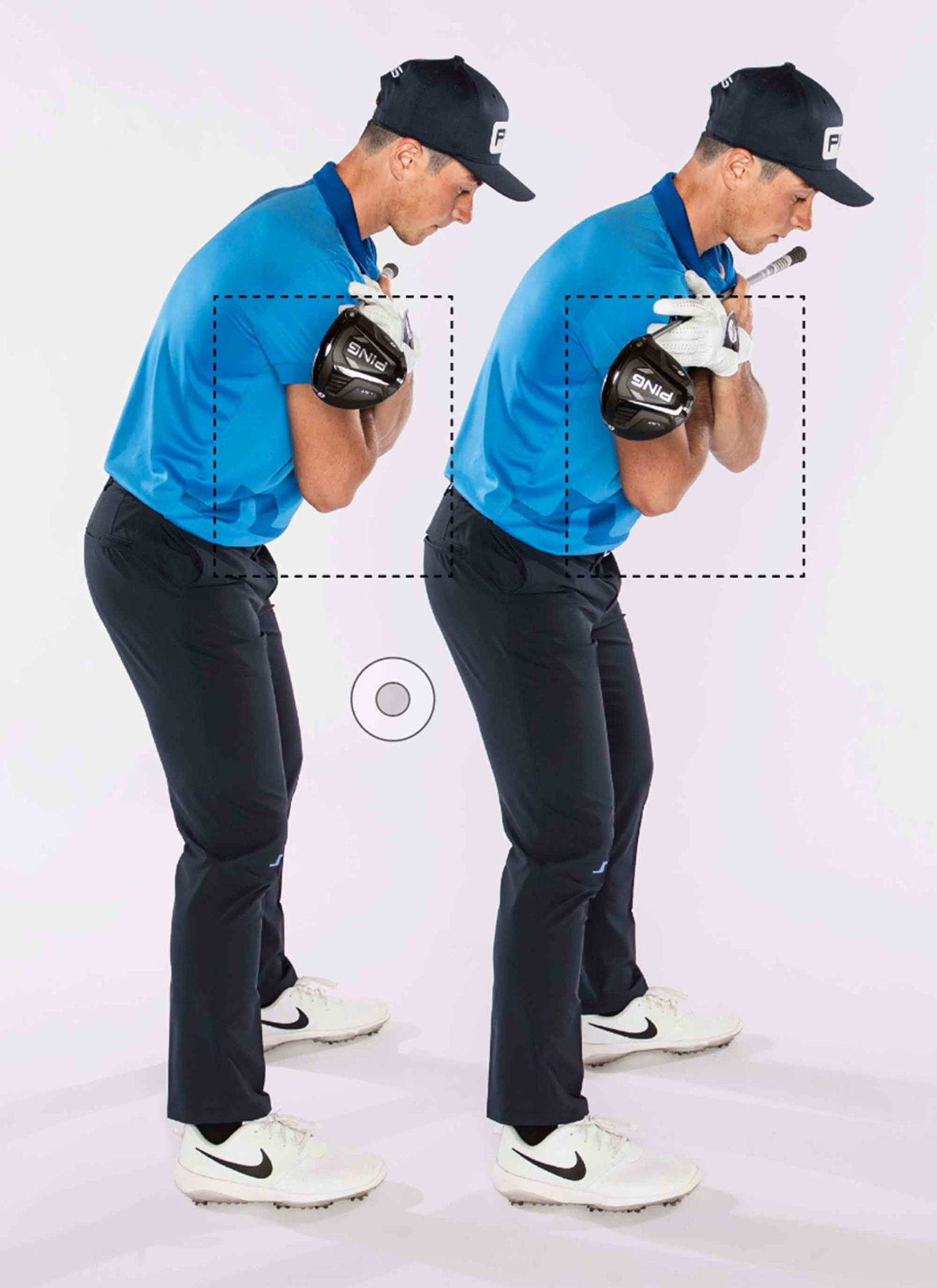

“Before I talk about the position of my left wrist, which helps me consistently square the face at impact, you might be curious about that pumping action I sometimes do at the top of the swing,” Hovland says. “To hit a power draw, I slow down the transition from backswing to downswing by pumping the club twice. It’s like a rehearsal, and it helps me create more clubhead speed. If you try it, you might find it also improves your timing, allowing you to complete a fuller backswing before starting the downswing. Another thing that can help you is getting to the top in a good position with your lead wrist. My lead wrist is in flexion [left], which means it’s slightly bowed (palm down). If your wrist is extended (palm up), the clubface will be open at the top. You’ll have to do something in the downswing quickly to close the face, or you’ll probably slice it. It’s a lot easier to avoid a slice if you fix your wrist position at the top of the swing.”

Speed everything up to generate more power

“My project has been increasing clubhead speed. To do that, I’m trying to make everything in my swing faster. It makes my hand path longer, my turn bigger, and I’m pushing harder off the ground [far right], which translates into a faster clubhead. That’s a big difference from what many amateurs do. They try to swing faster but don’t turn their hips or shoulders more. That restricts speed. It should feel like you’re letting the clubhead go [near right] instead of directing it through impact with your hands.”

Accuracy starts at address

“One of my tendencies is to aim too far right, and that’s when I get into trouble off the tee. My stock shot is a little fade. But when I’m lined up right of my target [near left], my instinct is to push my hand path out to make my swing go more left. But that changes my swing path and makes it harder to produce a quality fade. To avoid that, I make sure my shoulders and hips are in line with my target [far left]. Don’t ignore the importance of checking your alignment.”

Use a wedge the way it’s designed

“Hitting high, soft pitches used to be a challenge because of the flexion of my lead wrist [above]. Flexion is good in the full swing, but it makes it harder to get the ball way up – you hit down on it too much. To take advantage of a wedge’s loft when pitching, I now grip the club stronger with my left hand, meaning turning it away from the target, but weaker with my right hand. This combo puts my left wrist in extension [right] and lets the club glide, not dig, along the turf to create good loft.”

Create different chips from one swing

“I mostly play low chip shots, but on tour you need to elevate the ball, too. My basic chip setup is with the ball in the centre of my stance and my hands slightly ahead of it [middle photo, above]. To chip it higher or lower, I don’t change where my hands are or what I do during the swing – all I do is change my ball position. For a shot that flies lower and runs out, I play the ball just in front of my back foot [above, left]. For a higher shot, I play the ball off my instep and open the face [above, right]. Then I’m free to pick my landing spot and let feel take over.”

Photographs by Dom Furore