Just three months short of his 90th birthday – “level fives” in his language – Peter Alliss passed away overnight. Born in Berlin on February 28, 1931 (he was, at the time, the biggest baby in Europe, weighing in at 14 pounds 12 ounces), the doyen of golf commentating died peacefully in his sleep at home in England.

Eight times a Ryder Cup player and the winner of more than 20 events around the world, Alliss ended his distinguished playing career in the early 1970s and quickly made himself an almost indispensable part of tournament coverage on television the world over. No one in that business knew the game better; few were as quick-witted or humorous talking about what the man himself never forgot was just a game. As well as commentating regularly for the BBC, he also worked for ESPN and ABC Sports along with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Alliss came from a distinguished golfing family. His father, Percy, played four times for Great Britain & Ireland in the Ryder Cup and was a consistent tournament winner in the two decades preceding World War II.

“I never really saw my father play,” said the younger Alliss. “But he was a lovely golfer, the Luke Donald of his day, or a Gene Littler. He had a perfectly balanced swing and was a superb driver of the ball. His putting was a bit shaky, but if you look at the greens back then they were worse than my lawn. I got a hand-written letter from Henry Cotton when I won the Assistants Championship in 1951 or ’52. Dear Peter, many congratulations on your first victory. Your father was the sweetest swinger I’ve ever seen. What a beautiful player. Sincerely, Henry Cotton.”

“I came home one day from school to find a few of my father’s friends sitting at the kitchen table having a cup of tea and a chat,” he said. “’Round that table were Reg Whitcombe [1938 Open champion], Ernest Whitcombe [1924 Open runner-up], Alf Padgham [1936 Open champion], Alf Perry [1935 Open champion], Dick Burton [1939 Open champion] and my father. It was summer time and I remember Ernest saying he had to go. He had to get back to the club – on the bus – because he had a couple of lessons that evening. Changed days indeed.”

The young Alliss also made the acquaintance of Bobby Jones, caddieing for the great amateur in what was surely Jones’ last round of golf in the United Kingdom. It was just after the World War II at Parkstone Golf Club outside Bournemouth on England’s south coast. Jones, wearing his colonel’s uniform and with his tie tucked into his shirt, played with Alliss senior and Reg Whitcombe.

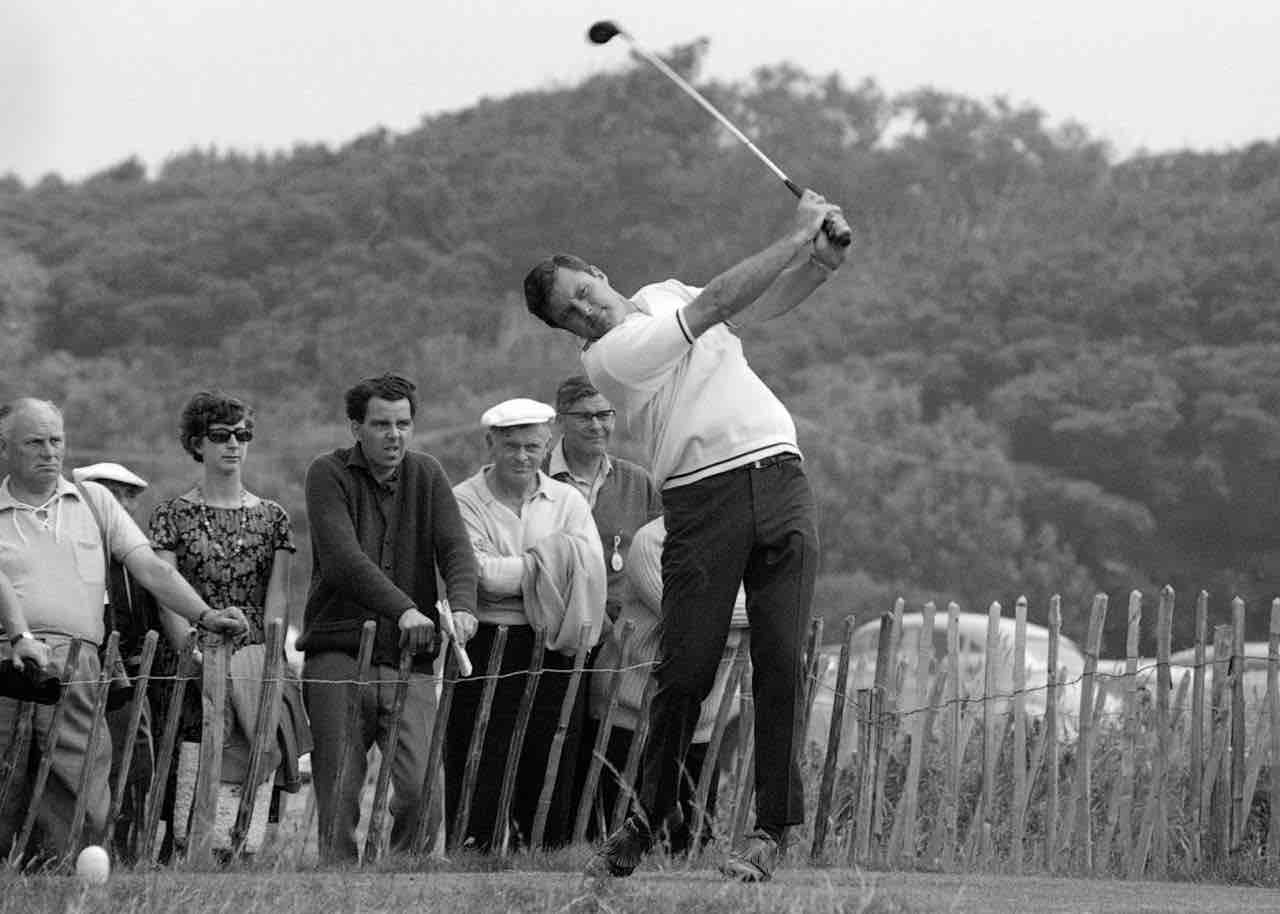

What often gets overlooked as he became more and more famous for his work with a microphone in hand was how good a player Peter Alliss was. Renowned for the smoothness and elegance of his full swing – and, later, terrible putting (the number plate on his car read ‘PUT3’) marked by a dreadful bout of the yips that, he claimed, began on the 11th green at Augusta National during a Masters – he twice played Arnold Palmer in Ryder Cup singles and finished unbeaten.

“I have a very good Ryder Cup record, mostly because of my fear of losing,” said Alliss, who went 10-15-5 on teams that went just 1-6-1. “I always had the attitude that ‘you weren’t going to beat me’. I believe you play the man, not the course. I played Arnold three times when he was at his peak and the only one I lost was a foursome. I beat him once and halved with him in singles. I also beat Billy Casper, Gay Brewer and Ken Venturi at various times, and halved with Tony Lema.”

There was more to Alliss than a formidable matchplay record, of course. In strokeplay he had his moments, although – as it was for his father – not winning an Open Championship was a lingering regret (he had five top-10 finishes in 25 appearances).

“Looking back, I was a good player,” he said modestly. “I was the best player in Europe in the 1960s, without ever winning The Open. I won my first tournament as far back as 1954, the Daks event at Little Aston, and my 21st and last in 1969. So I averaged more than one per year. There are only a handful of British players who have ever won more than I did. I’m certainly in the top 10. And my total prizemoney didn’t come to £30,000.

“I was a very good ball-striker in my time. And, despite my reputation, I could putt, too. You don’t win 20-odd times if you can’t putt. I would, over the course of a round, hole four or five putts of at least 20 feet. But I’d occasionally miss from no more than 15 inches. And I never knew why. I’ve seen film of myself in the mid-60s and I had hardly any backswing at all.”

Later, with all of the above behind him, Alliss’ shrewd observations on all aspects of the game were just part of his appeal as a commentator and author (he wrote 20 books on golf, from golf history to instruction to memoir). Unashamedly “un-PC”, he was unapologetically a product of his upbringing in the post-war years.

“I hate to see things going to waste,” he said. “I still go round switching lights off. I can’t bear to throw food away. I’m a relic of what influenced me when I was young. Courtesies and manners are very important to me. These days, people think you’re a dinosaur if you stand up when a lady enters the room, or if you write thank-you notes. I know it’s all progress, but it’s a different world from the one I grew up in.”

That view of modern life did occasionally get Alliss into trouble. He was, for example, not one who viewed golf in the 21st century as being necessarily superior to what had gone before.

“I do believe that the most skillful golfers were those who played between 1900 and 1920,” he said, his tongue only slightly in his cheek. “Look at the scores they did. JH Taylor won the Open at Deal around that time with scores averaging 73.5 or whatever. Look at the clubs they used. The balls weren’t round and didn’t go anywhere. The bunkers were never raked. The course was only 300 yards shorter than it is today. And the wind blew and the rain was still wet. I reckon you could take the best 20 players of today, give them the old balls and clubs in a goodish wind and they wouldn’t do what JH and his mates did.”

And he wasn’t above speaking his mind on what he sees today. A part of his character that was known to irritate a few of today’s stars.

“I watch a lot of golf on television these days,” he said not long ago. “Mostly because I don’t want the players to think I don’t know what is going on. Which is rather conceited of me. And sometimes I don’t believe what I am seeing. In Dubai recently I saw a player hit a shot from behind a tree, from rough, over a pond from about 180 yards out. Sure enough, he didn’t even get halfway across the bloody water. That sort of situation happens time and again. No wonder guys like that are also-rans; they don’t have any golfing brains. They don’t know how to play.”

Despite his long relationship with the biennial contest, the Ryder Cup was not immune either. Nor was another of the game’s sacred cows, the Masters.

“The Ryder Cup has taken on a little bit of a false persona, a bit like Augusta and the Masters,” said. “Just as Augusta National is supposed to be the greatest place in the world – it isn’t – the Ryder Cup is supposed to be the greatest golf event in the world – it isn’t either. But, because of the excitement each has generated over the years – the “War on the Shore” and all that other bollocks – it has become something it was never meant to be. Take the whole team-qualifying thing. I think the captains should just pick 12 men each and forget the rankings. It is too hurtful for someone to play quite well, finish 11th and not get picked.”

That ability to verbalise what many others think but never say was perhaps Alliss’ biggest skill during his career as a commentator. Of course, he learned at the feet of the master, former Sunday Times columnist, Henry Longhurst, who was the first journalist to transition successfully into broadcasting.

“I refused to do anything different when commentating in America,” Alliss said. “I certainly refused to say, ‘back side’. I remember one commentator saying, ‘And here is Faldo at 14, with wind gusting from his rear.’ I thought no, I’m not saying that. For me, it was always a bunker rather than a sand trap. I always tried to do what Longhurst told me: ‘Imagine you are sitting talking to a friend with one program between you.’ If there is nothing to say, it is better to do just that. The one thing I rarely do is take my eyes off the screen. Many people do, which I liken to someone turning to look at you as he drives the car.”

He could do it live, too. Towards the end of his life, Alliss toured Great Britain doing a one-man show that involved nothing more than him talking to the audience and answering questions. It was a rousing success, playing to packed houses all over the country.

“Yes, I turned down an OBE,” he said. “‘Other Buggers Efforts’ I called it. I was asked if I would accept it for ‘services to golf’. Which I thought was odd. Why should I get an OBE for doing my job? Now, if it were for all the work I have done with the wheelchair charity I have been involved with, we have raised about £7 million over the years, I could have seen the point. Even then, I just contribute my name and some time. Other people do all the real work. But not for bloody golf! So I said, ‘No.’

“If I was offered a knighthood, I think I would accept. I’d have more fun with it than ‘Sir Nick Faldo’ seems to do. He has that on his golf bag for goodness sake. It would sound better if it was ‘Sir Nicholas Faldo’ but once a Nick, always a Nick.”

Still, within it all there was a healthy dose of perspective. Life wasn’t always kind to Alliss and his wife, Jackie.

“Our daughter, Victoria, died when she was 10 years old,” he said. “She was very severely handicapped, having no central nervous system. She looked like a doll and hardly made a sound. That changed me. I used to get upset by little things and wonder why someone didn’t say hello for example. But, having had Victoria, I realised that the person who walks past without speaking might have problems I don’t know about. So all those things I used to worry about were eliminated from my life.”

And through his nearly four score years and 10, through the good, the bad and everything else in-between, Alliss was never above a bit of self-deprecation.

“I have no other talents really,” he once said. “I’ve only read about 10 books in my life. My father used to play the guitar and I played the drums until I was about 17. I dreamed of having a little band.”

Maybe in the next life. RIP.