Time is robbing Australia’s greatest-ever amateur golfer of his memory. But friends, foes and unearthed recordings offer new insights into his genius.

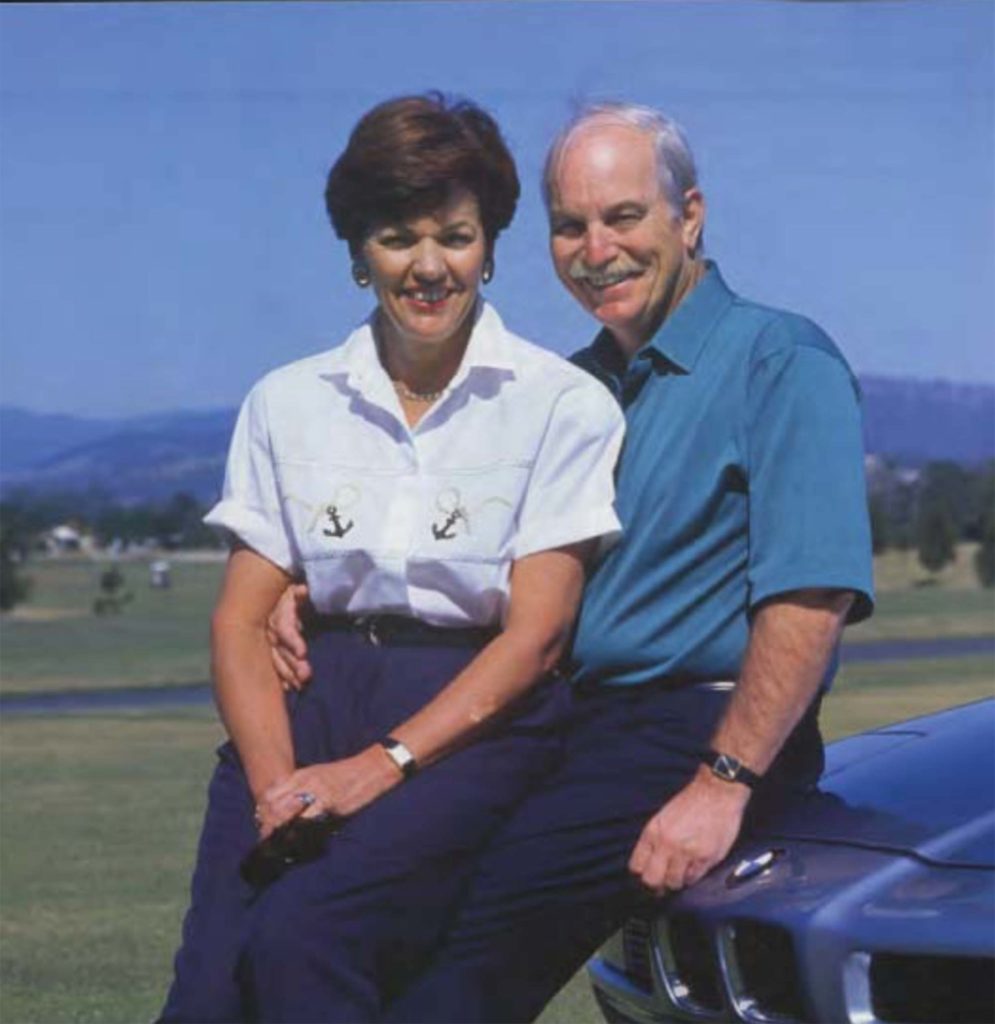

In the confines of the aged-care facility she now calls home, Wendy Gresham is going about her daily business when she’s distracted by movement in the living room corner. It’s her husband of 57 years, Tony, scrupulously working away on his golf swing, sans club. Like a spectator passing by a tournament driving range, Wendy stops momentarily for a peek. With his chosen club firmly gripped, Tony’s shoulders, arms and hips begin to turn slowly like clockwork as he takes everything back in unison. After a pause at the top, he accentuates the downswing motion a few times before executing the movement proper. His hands and clubhead are picture perfect at impact, synchronous at their meeting point, no need for retakes. He completes the action with a finishing pose that screams: he’s done this caper before, quite possibly for a living.

Wendy grins. For her, it’s akin to a trainer watching their prize-fighter shadow box in preparation for his next bout. There her man stands strong, off in his own little world without distraction, focused solely on the pursuit of excellence.

“He thinks I’m not watching,” she chuckles.

But she is. Wendy’s always looking out for Tony… has done for decades, as his loving companion, unbreakable confidant and sometimes caddie.

Anthony Yale Gresham, sadly, has forgotten more about the game of golf than most of us will ever learn. But even against all odds he still remembers the important bits. It’s why said air swings around the house mean so much. They serve not merely as a reminder of how fickle life can be, but as evidence that, while vascular dementia may be stripping Australia’s greatest-ever amateur golfer of his cognitive abilities, the bastard-disease has an uphill battle stealing his heart. The man famous in golf circles for choosing to play for love, not money, still very much loves what he did all those years for free. And, like an Eisenhower Trophy match or a Pennant Hills Golf Club championship decider, good luck taking him down.

The name Tony Gresham has been a conspicuous absence on the tee sheets at his beloved Pennant Hills Golf Club in recent months. Connected members and those close to him have known the reasons why, not that it makes it any easier to accept. But as the uninformed continue to ask questions of their club’s undisputed G.O.A.T. (greatest of all time), Gresham’s mind slowly drifts further into a state of irreversible decline.

At the time of writing, the man affectionately known as ‘Gresh’ had triggered two emergency calls to his home in the space of a week. The first saw the local fire brigade arrive to extinguish some burnt toast. The second – an ambulance callout in the middle of the night after Gresham hit the panic button on his emergency alert device. More alarming, however, was the fact he had no recollection of either incident.

“Dad’s gone downhill a little bit over the past 12 months,” reveals Scott Gresham, of his father. “Once you start taking away those independencies – things like driving, for example – [dementia sufferers] can slide pretty quickly.”

Licence or no licence, it’s been anything but a smooth ride for the Greshams in recent years. Family matriarch Wendy started a wretched run for the family when she was diagnosed with a brain tumour 20 years ago. While she was winning the battle for 18 of those years, it returned with force in 2020.

“Mum was on her deathbed,” Scott recalls. “Dad had no choice but to become a carer for her and, fortunately, she’s stable now, albeit living with a malignant brain tumour. But she’s doing OK.”

Adding to the misfortune of it all was Tony’s own deteriorating condition after his official diagnosis in 2021, which inevitably rendered him unable to provide for Wendy. So, the family made the decision to move the pair into an aged-care facility in Sydney’s north, where they remain today, still happy and content with life as they were the night they fell for one another. Oh, What A Night it was, late one evening back in ’63. Wendy was at a party when her date for the evening ditched her for the lads. Enter eagle-eyed Tony, a Romeo who swooped in like a thief in the night when Wendy least expected it.

“He was like a crow [to a golf ball] on the golf course,” Scott jokes. “He scooped her up and the rest is history.”

Ever the opportunist, it would be the first of many victories to come Tony’s way.

Birth of a legend

Barely 12 months had passed after the Greshams found true love when a 1964 Sydney newspaper clipping read: “Gresham Best In Golf.” The article was in reference to Gresham’s victory in a state amateur qualifier after he shot a 36-hole total of three-under par around his home track of ‘Penno’. Upon reflection, it may be the greatest piece of clairvoyance to ever make it to print, for state-title qualifiers would fade into insignificance compared to what he would go on to achieve.

The Sixties was a time of increased economic affluence in Australia, and money was of no great concern for Gresham. Two days after he left school, he entered his father’s tobacco distributing company, sweeping floors and filling up the shelves with cartons of cigarettes. He would stay on with his old man until he retired and sold the company in 1972. Gresham then moved across to the cigarette company that bought out his dad for the ensuring two years before he joined Rothmans in 1974 in its sports department, on April Fool’s Day, no less.

“I wasn’t quite sure when I first walked into the office whether I had a job,” joked Gresham in more jovial times. “But I did.”

He would later be seconded to the Rothman’s National Sport Foundation, which benefited junior sport until it was disbanded in 1994.

Holding down such secure employment, of course, meant investing time and money into his passion of golf was a luxury many others couldn’t afford. It was indeed a sign of the times, very different times to those that golfers – professional and amateur – find themselves in today.

Australian golf’s ‘Everywhere Man’ Mike Clayton recently penned of Gresham’s era: “It was a time when players saw that playing as an amateur was an unpaid but very serious ‘career’ in golf. In some ways, they had the best of it,” wrote Clayton for golf.org.au. “‘Gresh’ had a job and a normal life. Yet he played amateur golf with all the seriousness and dedication of the best pros in the country – and he could beat them, too.”

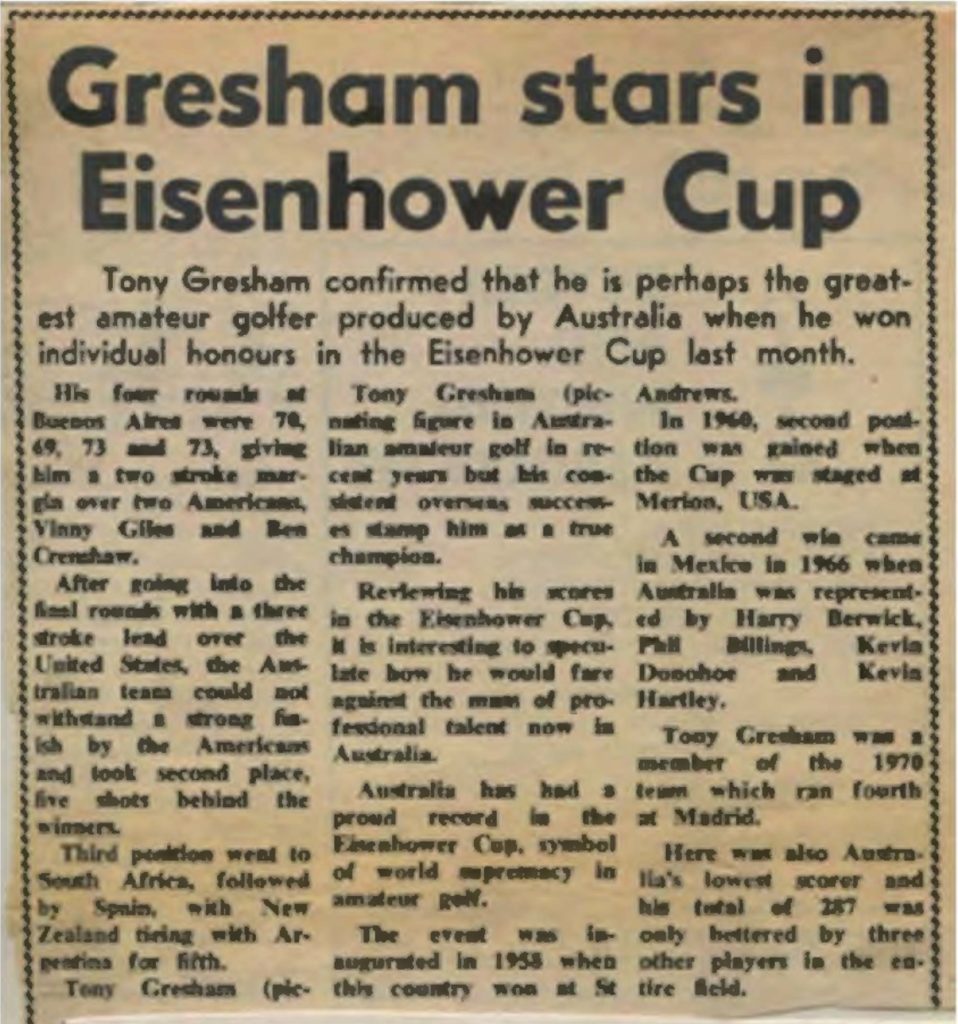

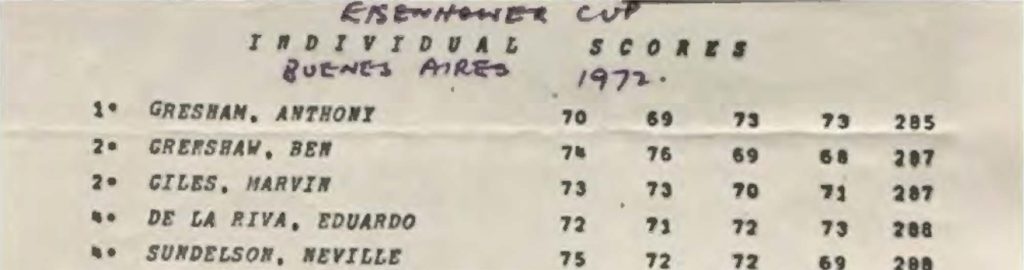

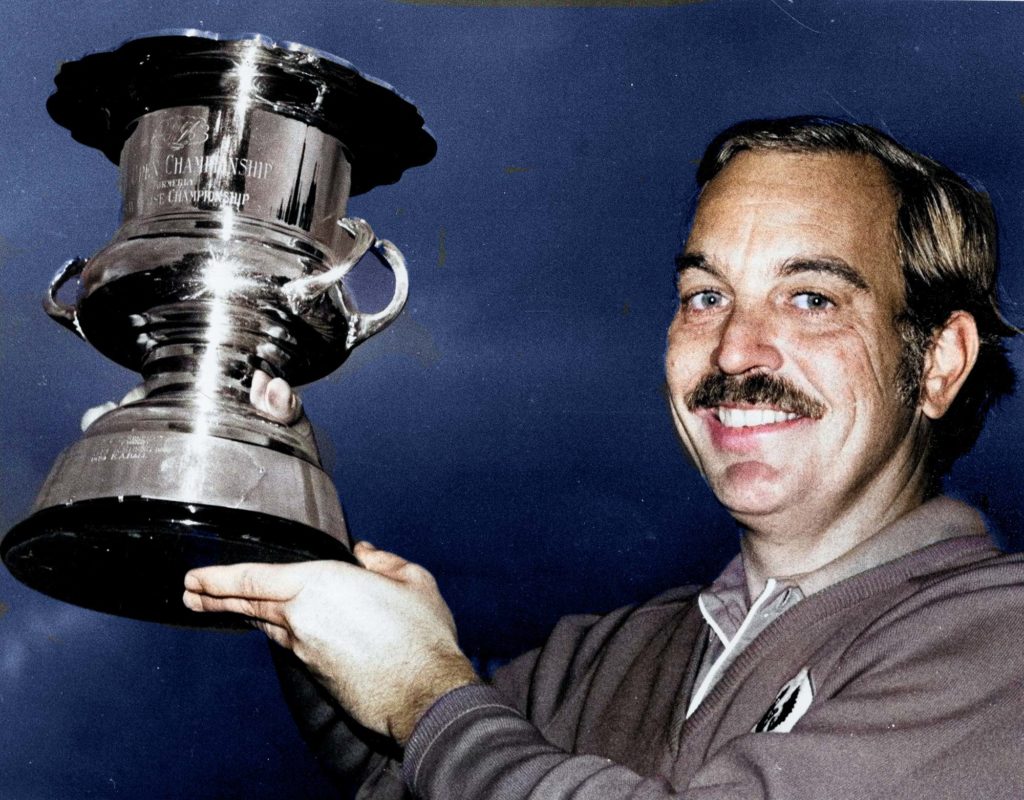

Indeed, he could. Australian Golf Digest published countless pieces on Gresham’s golf accolades over the years, particularly his exploits in the much-revered Eisenhower Trophy. Like how he established an insurmountable record for Australia in which he competed seven times (1968-1980). Or how he claimed individual honours in 1972 by holding off a young Ben Crenshaw, a future two-time Masters champion, to win the unofficial world title. There was also the head-shaking statistic of, during seven Eisenhower campaigns, Gresham’s score counting as one of Australia’s best three scores for every single round he played.

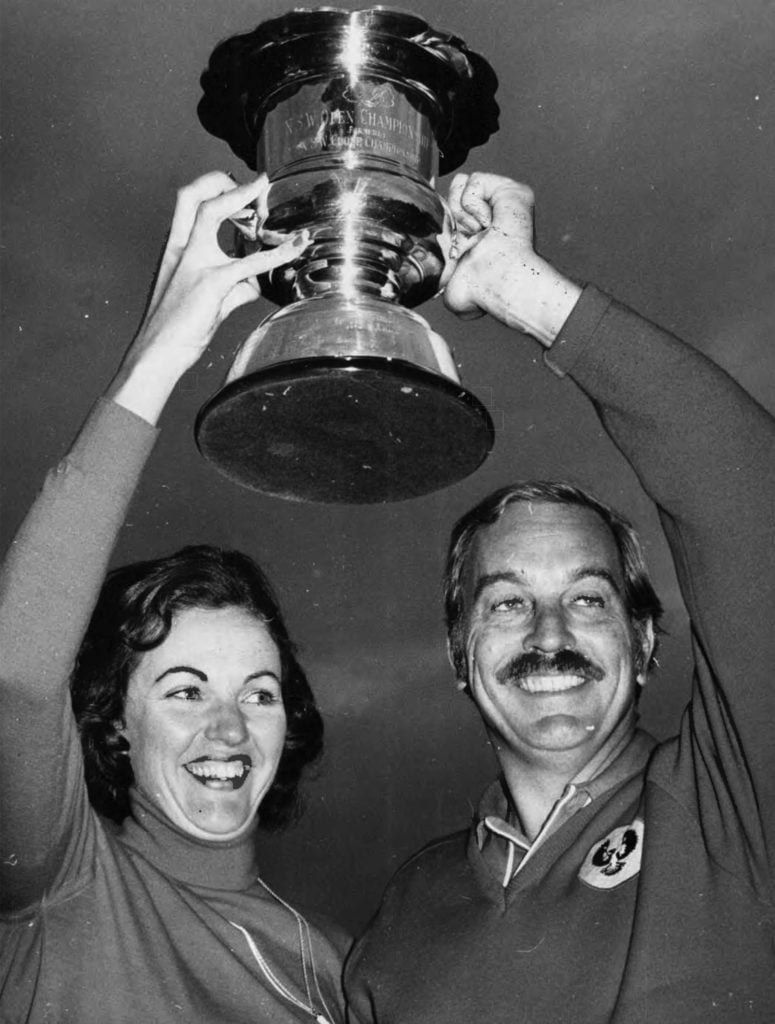

On home soil, Gresham’s dominance reigned supreme, too. He won the Australian Amateur title in 1977 and was runner-up on three occasions, claiming medallist honours four times. He captured the New South Wales Vardon Trophy in 13 of 15 years between 1968 and ’82. And who could forget the astonishing 25 club championships and eight senior club championships he won at Pennant Hills Golf Club among 50 individual victories and 28 mixed events with Wendy? Arguably his finest accomplishment of all, however, was beating the pros to win the 1975 NSW Open and 1978 South Australian Open.

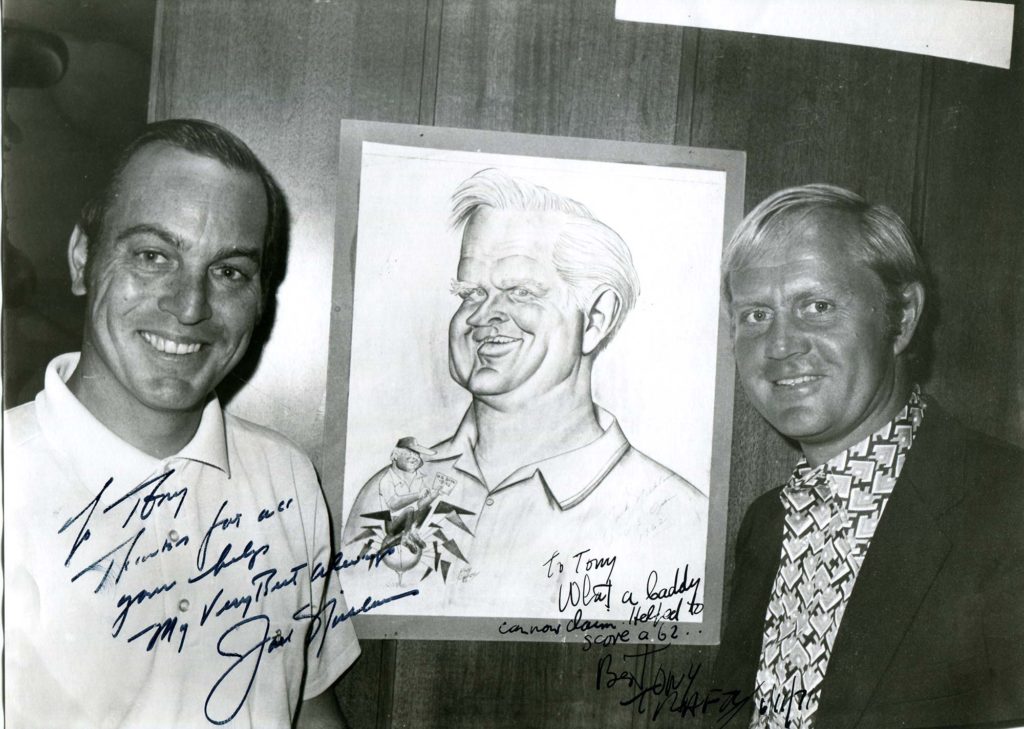

Gresh played with all the greats, including Jack Nicklaus, Greg Norman and Gary Player. He even caddied for Nicklaus during his 1971 NSW Open victory at Manly Golf Club – a moment revisited on Gresham’s 80th birthday when the Golden Bear sent a personal video message of congratulations, played to Tony during a club function celebrating his life in the game.

“You won a lot of tournaments and represented your country well,” said Nicklaus in the video link. “You’ve had a great career, great fun and were a great friend to me. But now, you’re as old as I am!”

It all begs a very obvious question: if the greatest player of all time rated you, why didn’t you turn pro?

‘Don’t cry, dear. It’s just your father’

Just how does one become Australia’s greatest-ever amateur golfer? Conventional wisdom suggests the very best amateurs nearly always transition to the professional ranks, in any sport. Why would golfers be any different, particularly given the endless amount of riches on offer?

As legendary Canadian ball-striker Moe Norman once said, “What do you do with 27 toasters?”

For Gresham, a man who was consistently beating the pros at their own game, let alone his amateur peers, not succumbing to the temptations of the lucrative play-for-pay ranks – nothing compared to today’s riches on offer, granted – was made somewhat easier after he returned home from the gruelling Eisenhower Trophy campaign of 1972. Just days after knocking off Crenshaw for individual honours, Gresham turned into the driveaway of his St Ives abode, expecting a warm reception from Wendy and their two kids – daughter Tori, 4, and son Scott, 2. He received anything but.

“When Dad walked through the front door, Tori just started screaming and was an uncontrollable mess,” recalls Scott, now 51. “She didn’t recognise him after he had been away. That was the moment Dad realised he didn’t want to play golf for a living because he knew being overseas on tour for nine months of the year was going to be even harder. He had absolutely no interest in not being there for his family.”

Gresham himself fielded numerous questions about the topic over the journey, all provoking a similar response from the straight-shooter. “It was very straightforward,” he told Australian Golf Digest in a 2008 interview. “I’ve got two answers for it. One, I had a family. And the other one, I didn’t think I was good enough. I might have won a lot of events, but it’s a different thing when you’re a pro. The old muscles tighten up a lot.”

While incredibly humble as it may have been, not many were buying his second excuse.

‘He’s the best I’ve seen’

Ask anyone who came up against him during the peak of his career and they’ll tell you Tony Gresham was in a league of his own.

“He was the best amateur golfer I ever played against,” says Randall Vines, 1972 Australian PGA champion. “If Tony had turned pro at a young age, I am certain he would have been very successful.”

PGA of Australia chairman and decorated pro Rodger Davis concurs.

“Tony was definitely our best amateur over a long period of time,” Davis says. “You always had good amateurs come and go, but Tony was there for what seemed like centuries. He kept representing Australia and winning. You’ve got to be a hell of a player to do that. I actually thought when he turned 50 that he may have gone over to the seniors tour in America but, no, Tony was quite happy to be at home and do what he’s been doing for decades.”

So, what exactly made Gresham so bloody good? Was it his ball-striking? Was his short game simply a class above? Did he have some uncanny ability to make more putts than his opponents? Was it an uncanny knack to pull off the winning shot when the moment called for it? It was a combination of all that and more.

“Of all the golfers I’ve played with or against, Tony would have to be the straightest iron player I’ve ever seen,” says good friend and long-time rival Gerry Power.

“He would talk to you between shots like it was just a casual round, but when he came within 10 metres of his ball, he just flipped a switch and changed. All of a sudden he was in his own little world and so incredibly focused, and sure enough, he would execute the shot that was required, every time. He had the ability to be the best pro golfer in Australia, in my mind. He was that good.”

Power recalls the time, after being eliminated himself earlier in the tournament, he caddied for Gresham during the later stages of the French Amateur Championship. After progressing to the second hole of a playoff, Gresham sprayed his tee-shot into the trees on the right, while his opponent found the middle of the fairway.

“I said to him, ‘Mate, just take your medicine here. Hit it to 100 [metres] out, you know how good you are from that range.’ Tony wasn’t having a bar of that. He said to me, ‘You see that soccer ball-sized gap in the tree? I think I can get it through that.’ I couldn’t believe he was even contemplating that in such a big tournament. If he misses this gap, it’s all over – he’ll never find his ball again. Low and behold, he pierces this gap and hits it to about 10 feet, holes the birdie putt to win the match. That’s what he was like.”

Such stories of Gresham’s sorcery are far too common for it to be all a fanciful fairytale. One of the most famous has become legend among the Pennant Hills Golf Club faithful – the time Gresham broke the heart of his club championship final opponent, Greg Wicks.

Wicks, a very good player in his own right and a noted big hitter, tells of driving the 15th hole not once but twice during their match. Keep in mind, this is an uphill par 4 measuring 285 metres with a green surrounded by bunkers. It isn’t exactly a big target from the back tees. Both should have been match-winning blows for Wicks.

The club’s general manager, Barnaby Sumner takes up the story: “On the first occasion, Tony managed to get up and down and square the hole, matching Greg’s two-putt birdie,” he says. “On the second occasion, Greg lost the hole, with Tony holing out from the fairway for an eagle. There is still a hint of frustration in Greg’s voice when he retells this story, but as he notes, ‘That’s just how good Tony Gresham was.’ Even when you thought you had him, he could turn the tables and take away your advantage.”

Davis knows all too well of Gresham’s penchant for pinching matches late in proceedings.

“It didn’t matter who played Gresh at Pennant Hills, you couldn’t beat him,” he recalls. “The best players in Australia tried and I don’t think any of them ever succeeded.

“Every time I played against him, he just never gave up. Because he had such a great short game, the amount of times in pennants or state matches when you got out to a lead and he had a poor start, you just knew he was going to get you if you didn’t keep going. It’s why many of us were dumbfounded as to why he never turned pro. But the pro tour isn’t for everyone. It’s knocked over a lot of people. But it’s a shame we never saw Gresh give it a go because, in my opinion, he would have made it, no question.”

A plus-2 handicap in his prime, such a figure barely raises an eyebrow in today’s talent-laden amateur ranks. But comparing abilities of the best amateurs of 2022 to Gresham is absolutely futile, according to Davis.

“It’s a lot easier to turn pro now,” he says. “When we had to turn pro, we had to go through the pro-shop system, which was a total pain in the arse. Today, you just say you’re pro and that’s it. You go to Q-school and away you go.

“Gresh being a plus-2 marker back then was the equivalent of being a plus-8 marker today. To even get a plus-handicap back then was virtually impossible because 85 percent of your scores had to be recorded away from your home course.”

Davis is spot on. So hard, in fact, was it to become a plus-marker in the ’70s that, at one point, Gresham was the only golfer in Australia to boast one. “In NSW, there were 12 of us all off scratch handicaps over a four-year period and none of us could get anywhere near Gresh. We went on to turn pro.”

A master escape artist, so good was Gresham’s ability to get himself out of sticky situations, some liked to joke he must have been cheating.

“There were times where he’d get out of an impossible lie in a bunker and he’d hit it to a few feet of the pin and you’d swear he must have thrown it out,” laughs Power. “He was that good!”

Bruce Jones, Pennant Hills Golf Club’s digital historian, has logged countless hours compiling Gresham’s long list of achievements for safe keeping. He says they’re records that are unlikely to ever be surpassed.

“When I joined Pennant Hills 30 years ago and met Tony, I began to appreciate his legendary status within the club,” Jones says. “It was during my assembling of his lifetime achievements that I was blown away by his astonishing golf record and appreciated I was actually assembling the story of ‘Australia’s Greatest Ever Amateur Golfer’.”

One last round?

It’s ironic that one of Gresham’s first experiences in the game came about by fixing grips at Avondale Golf Club under the tutelage of Les Chapman.

If Scott Gresham gets his way, it may also be the site of his father’s final round of golf. Among his to-do list in the coming days, weeks and months is to get his dad out on the golf course (where Scott is a member) to see if he still has the ‘game’.

“I’ve been talking about it for a while, but I really want to take Dad out for a hit with the grandkids, just to see if he’s still got the ability to do what he’s done all his life,” Scott says. “He walks around the house doing those air swings, so he clearly still has the fire within. I’m pretty sure he hasn’t lost the ability or memory of how to swing. He’s probably just lost the ability to keep score [laughs].”

Laughing about the cards they have been dealt has been a great coping mechanism for the Greshams. While on one hand it’s heartbreaking for them to see such a brilliant mind slipping away, taking all that creativity and imagination with it, it’s also brought them closer together to make the most of time.

“Dementia does provide a few laughs when the patient is lucid,” Scott admits, “but those moments are becoming increasingly few and far between with Dad. You just learn to laugh and cry.”

As the search for a cure continues, Please remember the real me when I cannot remember you has become a rallying cry for those dealing with dementia. For Scott, a forgotten piece of his father’s legacy hides away from the golf course and doesn’t involve trophies.

“Dad has always taken such great pride in his grandchildren’s exploits on the sporting field, whether it be golf or whatever sport they play,” he says.

“Nearly 50 years ago he made the selfless decision to not turn pro, when he would almost certainly have made a career out of it. Instead, he made the choice to remain at home and take great joy at being a dedicated husband and wonderful dad, father-in-law and grandfather who is greatly loved.

“Golf, for him, was a lifelong hobby that brought him tremendous joy.”

That, above all else, will be Tony Gresham’s greatest lesson of all.