To gain a sense of Peter Thomson the golf-course architect, one needs to do more than just play and appreciate his golf courses. You also need to hear what it was like to work alongside him.

It was English naval commander John Harris who guided Thomson initially before he struck a long and fruitful partnership with another Brit in Mike Wolveridge. Collectively, the firm (which Ross Perrett later joined and remains part of) has designed courses in China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Scotland, Singapore, Thailand, Turkey and Australia.

The geographic synergy is palpable. Thomson won titles in almost all of those countries and became revered as a figurehead in many. His success as a golfer unquestionably had a positive impact on his fledgling design business – as has been the case for the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Greg Norman and others in more recent times. A mantelpiece covered in trophies opens doors in the golf world, as Thomson and co. quickly discovered.

Wolveridge chuckles as he recalls the way his good friend was known as “Sir Thomson” in Japan. “At first, we were influenced by two things,” Wolveridge says of their union in 1965. “One was the fact the British Open champion had decided to go into this architectural business, and he was winning in Japan and we got just about every job in Japan. You got all the money you needed and we did 30 [course designs]. They just wanted the name.”

Australia would become a focal point during the design heyday of the 1980s to early 2000s. In rapid succession came an array of courses in places as varied as the Murray River, Alice Springs, Sydney, Hobart, the Gold Coast, Tropical North Queensland and, of course, Thomson’s beloved Victoria.

A familiar approach to design appeared even if the sites and locations varied. Thomson liked golfers to think, while providing options and avenues for a range of skill levels. Yet his expanding portfolio became eye-of-the-beholder stuff. One critic told Australian Golf Digest that Thomson “obsessed over making holes really difficult for elite players” on several of his better courses.

Pot bunkers appeared with ubiquity, as ‘Peter Thomson bunkers’ became a common refrain, sometimes uttered in praise and other times in derision. Fellow course architect Neil Crafter gives a nod to the significance of the pot bunker in Thomson’s arsenal, while acknowledging there were more arrows in his design quiver.

“Peter’s design style in his formative days was perhaps influenced more by American design, but by the early 1980s his British experiences as a champion golfer on links courses influenced him more and more, with pot bunkers becoming a significant signature of his work. Peter will be remembered as a pioneer architect who took the game of golf to the world, especially into Asia,” Crafter says, adding that his knowledge of Thomson was twofold.

“I was fortunate enough to caddie for Peter as a young amateur golfer. My father Brian was Peter’s TV commentary partner on the ABC golf telecasts for many years and he arranged with Peter for me to caddie for him here in Adelaide at Grange East in a West Lakes Classic. Peter would have been in his late 40s or early 50s at this time and, while still playing good golf, was not that competitive against the ‘young bucks’ any more. Peter made the cut and I recall on the Sunday, finishing our round about lunchtime and catching up with Dad behind the 18th green before he started the telecast. He asked PT how he went and he laconically replied: ‘Not that well, really. I don’t play so well in the mornings. I won all my championships in the afternoon.’

“Delivered with the dry wit that marked Peter Thomson. I will never forget it. He will be sadly missed by the Crafter family.”

Applied Principles

Thomson penned several revealing columns for US Golf Digest during the 1980s but his first, published in February 1987, was a telling opening foray. In it he explained his thoughts on writing and course design and how the two disciplines intertwined.

“When I first took to journalism, my kind but stern mentor laid down the principle that if my grandmother couldn’t understand what I was writing about, it was a lousy piece of composition,” he wrote. “I’ve come to carry this along into golf architecture. If my grandma can’t play it, it has to be a lousy course.”

Simplicity was something of a hallmark of Thomson’s approach to golf, to design and to life. “Or common sense,” adds Wolveridge, who worked alongside Thomson for 40 years.

“He was imminently sensible,” Wolveridge says, adding that the pair favoured the MacKenzie style of architecture more than anything. “He didn’t like penalising people [because] it mainly penalised the poor golfer and not the good golfer. Peter carried a common sense attitude to architecture all the way through. Common sense, not trying to be smart or stupid or spectacular. He’s probably the most sensible fellow on any subject.”

Not everything in their body of work was brilliant, but – much like Thomson the golfer – he was resolute in his architectural decisiveness. Mike Clayton, who in many ways is Thomson’s successor in mixing thoughtful design and considered writing, delivered twin viewpoints in the wake of Thomson’s passing on June 20. Clayton lauded how Thomson was driven not by profit but by what was best for the game, yet admitted they had professional differences.

“It’s fair to say I didn’t ever really like the way he made his courses look because I think they were too mounded, and as a general rule built pot bunkers as a formula,” Clayton said recently. “He tried to suit a style to the piece of land rather than finding a style that suited the piece of land – if that’s a general criticism. But we thought exactly the same about how the game should be played.”

Which is exactly how Thomson would want golfers to think: using brains over brawn. In many ways the tactical beauty of links golf shines through him and few Peter Thomson courses required you to be Peter Thomson in order to play them.

“He liked to fool people,” Wolveridge concedes. “He loved to do a green and deliberately get out all the theodolites, and so on, to make sure that it broke against the way everyone would think it would. So we would do a couple of greens that would break the other way to stuff everybody up. He used to go and watch that and it would tickle him to death – he liked that more than anything. He’d stand there with his putter over his shoulder and get the giggles. I would too, to a degree.

“He liked the surprise and the fairness. He very much had an attitude that championship golf was about not just playing nicely, [that it should also test] your attitude to fairness and to failure. He didn’t worry about failure; he didn’t regard it as failure. He thought part of winning was to handle those things.”

Of their most famous design trait, the garrulous Wolveridge is more phlegmatic when speaking about the pots that often were deep enough and dark enough to develop film in.

“We thought that was the proper way to do a bunker,” he says. “If you get in a bunker, it’s a hazard. That was a positional golf hazard – if you’re in that, you weren’t supposed to go there. So you had no right of progress. And that’s what made you frightened off the tee. The golfers of today, quite frankly, they’re not frightened off the tee. They get into bunkers and they’ve got the skill to get it out, a perfect lie and they generally don’t have lips on them. So it’s been our collective view that if you get in a bunker, you’re not entitled to knock it on the green. It was a hazard.”

One thing Thomson hated was seeing bunkers positioned behind greens, Wolveridge says. “They are hazards to go over or around only.”

Over or around, and sometimes perhaps shrewdly past. Peter Thomson the course architect gave golfers a route to his targets where the path and its pitfalls were well defined. The rest he left up to you, a timeless element that won’t change now that he’s sadly no longer with us.

Ten of Thomson’s Leading Layouts

Moonah Links

Thomson authored the mighty, brutal Open course while partner Ross Perrett concurrently penned the adjacent Legends course. Both receive collaborative design credit for the two layouts, but their respective focuses were shared thusly. The Open course staged our national championship twice, in 2003 and 2005, and earned a reputation for being fiercely difficult from the back markers when the wind howls. Dotted by Thomson’s signature pot bunkers, golfers are constantly challenged by the pots, the undulating terrain and the conditions peppering the Bass Strait locale. Robert Allenby’s victorious Australian Open campaign in ’05 highlighted the capricious nature of the layout when he opened with an exceptional 63 yet three days later hung on thanks to a closing 77.

The Legends, which these days sits higher on our Top 100 Courses ranking (34th versus 41st) is a less taxing but infinitely enjoyable excursion through different terrain. Together they make a fine double act on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula.

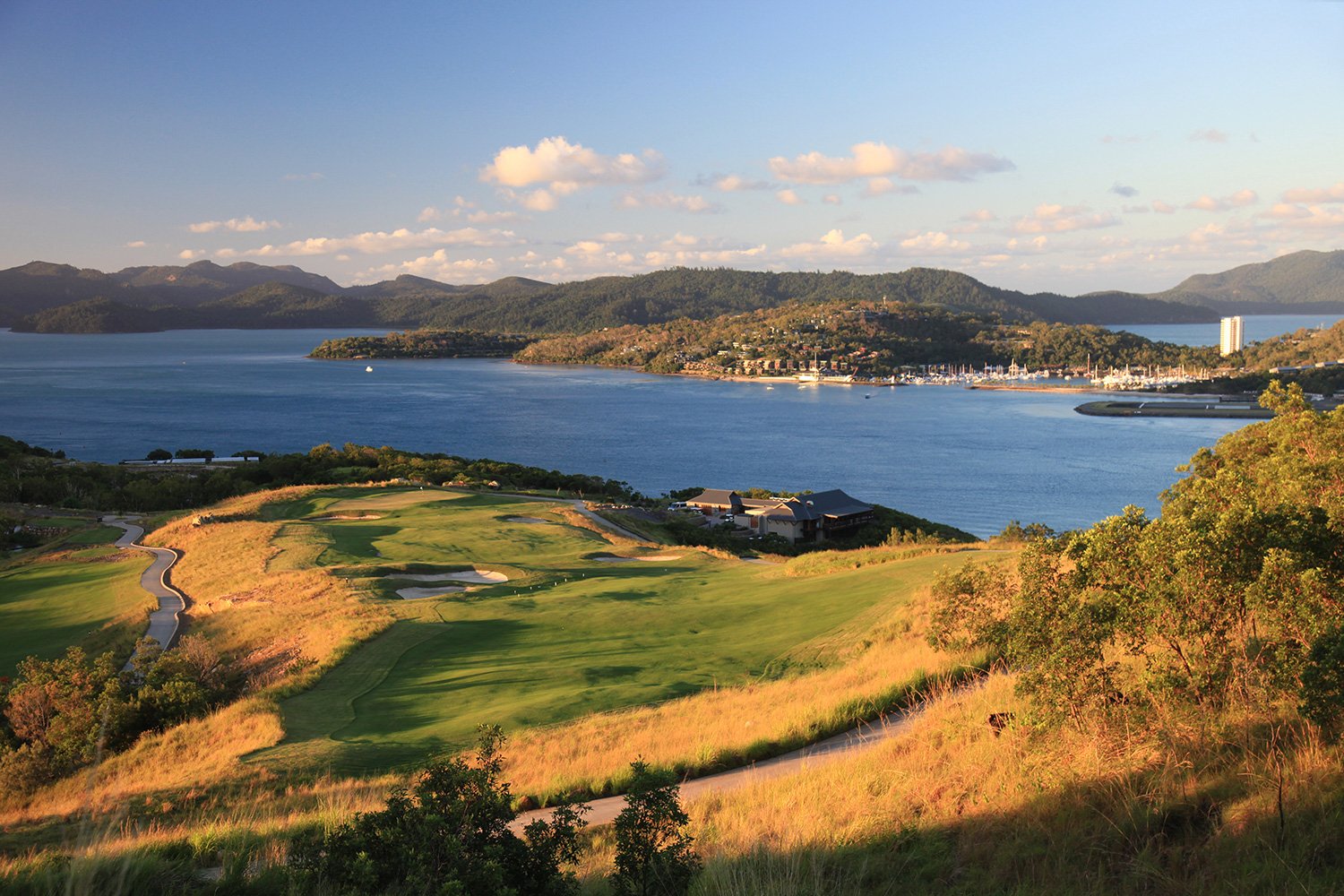

Hamilton Island Golf Club

As of 2018, this is the highest-ranked TP layout in Australia, according to Australian Golf Digest’s legion of course raters. (Some higher-ranked courses have received the ‘Thomson touch’ without being full-scale redesigns.) Now open for nine years, Hamilton Island was a demanding project for the Thomson Perrett firm. Mired in red tape for longer than anyone at TP would care to remember and with logistical and environmental concerns throughout, the end result was a stunning course with a backdrop as picturesque as they come.

Located on Dent Island, across a narrow passage from Hamilton Island, the dramatic course on its equally dramatic site fittingly builds to a crescendo while simultaneously presenting striking, challenging holes from the outset. It’s an unlikely TP course in an unlikely TP setting, yet the combination most definitely stands out even if the location is a world away from Britain, Asia, Melbourne or any other Thomson course.

www.hamiltonislandgolfclub.com.au

Tura Beach Country Club

Underrated can be an overused word in golf-course architecture circles, but it applies aptly here. Tura Beach, on the coast of southern New South Wales, was an early Thomson design on land that would bring out the best of his creativity. Tura Beach features considerable terrain changes, with sloping land the most prominent feature. This, combined with delightfully sandy soil, gave rise to one of the better country layouts in the state and in the nation.

Three main sections distinguish the course. There’s the lower, flatter, coastal holes early on the front nine; the hillier, sharply undulating region where most of the remaining holes reside; plus the pocket of holes farthest from the clubhouse played late in the back nine on their own slice of land across a road. It’s an engaging course in a magical location worth seeing for any Thomson aficionado.

www.turabeachcountryclub.com.au

Links Hope Island

This was the golf course that demonstrated the nous Thomson and his design partners Mike Wolveridge and Ross Perrett possessed. The first major collaboration involving all three men, it turned heads immediately when it opened in 1993. The world had the pleasure of seeing Hope Island four years later when it hosted an elite international field for the 1997 Johnnie Walker Classic, and ever since myriad golfers have enjoyed the course’s links-style topography in the sun and splendour of the Gold Coast.

Intermingling the tenacious Thomson pot bunkers with the more recognisable Queensland features of water hazards and tropical vegetation, Hope Island brought the best traits of the great British links to a setting in which such characteristics might feel unfamiliar. Yet it worked, delivering golfers an experience that remains just as enticing 25 years later.

Yarrawonga Mulwala Golf Club Resort

When it comes to playing golf along the Murray River, the biggest problem is not deciding where to play, but choosing where not to play. One of the places rarely bypassed is the 45-hole complex at Yarrawonga Mulwala. Thomson designed the entire Murray course, including the lone hole along the mighty watercourse where the river is actually in play, and half the Lake course. But if you’re seeking an array of Peter Thomson pot bunkers, you’re out of luck. Instead, Thomson kept the bunkering subtler and chose to work within the stands of majestic river gums by crafting a layout that fits with the riverland landscape. The Lake course offers a point of difference. Flanked by fewer large trees and situated upon more varied terrain, this layout fits comfortably in its setting and – as the name indicates – uses water more prominently. Thomson and co. created 27 holes you could play every day.

Black Bull Golf Club

Officially the final course to carry the Thomson design touch (although Club Mandalay, on the outskirts of Melbourne, can arguably make the same claim), Black Bull is the youngest but best course on the Murray River where the five-time British Open winner worked prolifically as a course architect. Black Bull opened progressively before finally reaching completion in 2015 with the unveiling of the final few holes. Since then, it has become a must-play addition to the already healthy Murray golf scene.

Black Bull represented a return to the TP design traits with which Australian golfers have become so familiar. It bears a resemblance to the firm’s work at Hope Island, although in a vastly different setting. Set flush against the edge of Lake Mulwala on the Victorian side of the border, Black Bull is open, exposed and ripples across the land as it builds to an exciting – and exacting – finish.

Rich River Golf Club

Some golfers hunt; others like to be fed. At Rich River, they’re fed a steady diet of relentlessly solid golf holes. Another Murray layout blessed with two courses, Rich River felt Thomson’s input 20 years ago when he masterminded a significant redesign of the East course. While the West and East courses don’t offer as many differences as the twin courses at Yarrawonga Mulwala, they do complement each other well.

On the East, Thomson injected strategy into the layout while working with what the layout naturally afforded him. The sprawling bunkers are more pans than pots, however Thomson’s design DNA is felt throughout. Rich River provides golfers with ample room to move and that space is evident with not only the bunkers and generous landing areas but also the huge greens. Putts of 20 or more metres are not uncommon – which no doubt appealed to Thomson’s love of the British links.

The Thomson name will live on at Rich River with TP Golf now undertaking a course masterplan for both layouts.

Lakeside Golf Club Camden

Australia’s most populous city received the Thomson treatment in 1993 when the course then known as Camden Lakeside opened in Sydney’s south-west. More rural than urban at the time, Lakeside also paved the way for more golf in that corner of the city.

This course was Thomson, Wolveridge and Perrett really hitting their design straps. The mostly open layout is dotted with a sea of pot bunkers that dictate terms on most holes, while canted fairways and raised greens add to the richness of its character.

Some modern putting surfaces are harder to read than hieroglyphics. Conversely, the greens at Lakeside mightn’t be easy to reach but they’re not difficult to decipher once you’re aboard. The great man must have wanted to provide some reward, perhaps figuring golfers had worked hard enough by that point.

Mirage Country Club

One of two layouts in the tropics of north Queensland designed by Thomson’s firm, Mirage represented a vastly new climate and environment to delve into. Working in concert with former design associate (and Tropical North Queensland resident) Mike Wolveridge, the pair gave Port Douglas a premier resort course with fairways separated from each other by tropical vegetation and mangrove waterways.

The course has something of a ‘satanic’ routing, with the unusual mix of six par 3s, six par 4s and six par 5s, while two holes run alongside renowned Four Mile Beach.

Launched with great fanfare at the height of Christopher Skase’s infamous extravagance, Mirage sadly fell into disrepair for a time during the 1990s but these days is returning to its best. Ironically, exactly 30 years to the month since it opened – and sadly the week of Peter’s passing – Mirage’s new owners approved a complete renovation of all 18 greens to be supervised by Wolveridge.

Ballarat Golf Club

Thomson and Perrett exercised their design diversity when it came to Ballarat. Neither coastal nor tropical, the location still comfortably lent itself to their particular style when they came to the famous gold rush town on a redesign mission late last decade. Using land additional to that already containing the existing course (which dates back to 1895) as well as reworking the current holes, TP struck gold by authoring one of Australia’s finest regional golf courses.

The new-look Ballarat is largely open but doesn’t rely on Thomson’s trademark pot bunkers. Instead, the bigger features are allowed to dominate as the course meanders amid a series of watercourses and flanking treelines. The club has hosted the PGA of Australia’s National Futures Championship each spring since 2014 and competitors in the world’s richest trainee tournament have routinely praised the 6,283-metre layout.