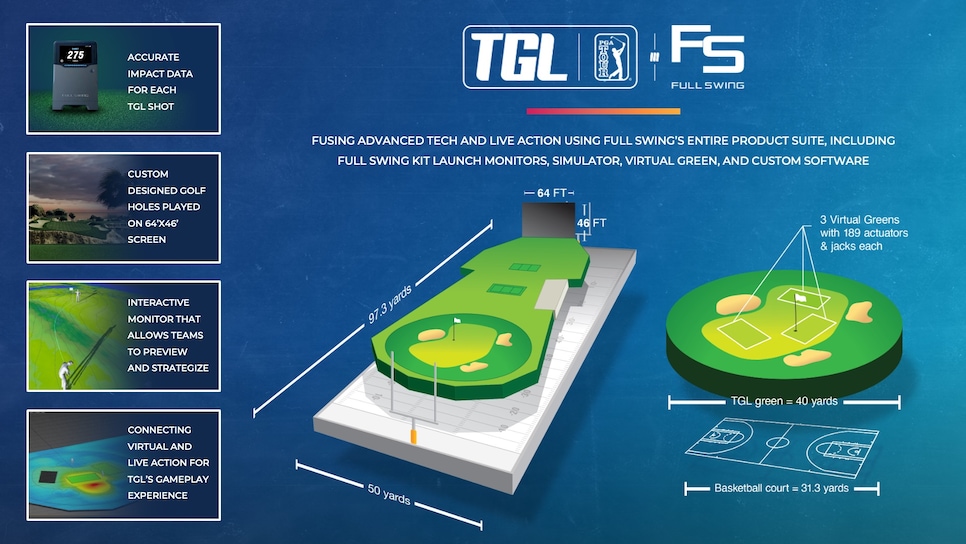

It’s billed as a tech-infused league, which is a fancy way of saying futuristic. The dilemma with TGL is it feels like something we’ve seen before.

For all the hype surrounding the mixed-reality circuit headlined by Tiger Woods and Rory McIlroy, there’s an undercurrent of worry that gains power with every drip from the league’s prolonged rollout: TGL, which has a number of influential entities involved and a sneaky amount of importance riding on it… might miss—and miss big. Might is the operative word. It is unfair to bury what has not lived, and TGL will ultimately be judged by its product rather than the promotion surrounding it. Yet two months away from its launch on January 9, what we know about TGL—and just as importantly, what we don’t know—seems to be following a blueprint the sport has already seen fall short.

TGL announces Tiger Woods as owner and player for tech league’s sixth team, Jupiter Links

Let’s start with the players in question, for that is arguably the foundation from which TGL is trying to build. It has Woods, who continues to be the fulcrum of the sport despite (we gesture wildly to the past three years). It has McIlroy, the biggest draw in the game, and popular stars in Rickie Fowler, Justin Thomas and Max Homa. But it’s missing three of the top four players in the world in Scottie Scheffler, Viktor Hovland and Jon Rahm (who pulled out of TGL last week), along with Jordan Spieth, who is arguably the most entertaining player in the sport.

To fill out this made-for-TV spectacle, roughly a third of TGL’s roster does not classify as household names, begging the question of why fans would tune in to watch players they normally would not pay to see. There’s also the not-insignificant notion that personality is a big sell with this format, with the need for its competitors to engage in sledging and banter to give this juice. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen with other exhibitions, most professional golfers tend to default to tepid and boring interviews. That includes Woods, who has too much to lose to be as colourful on camera as he is off.

Which transitions into the tone of TGL. It should be low stakes and loose and ridiculous. What it’s been is very much not that, judging by its marketing and publicisation. There was a cringe-inducing hype video for Team Atlanta (more on this in a second), along with a very staged clip of Collin Morikawa finding out he was part of the Los Angeles club. Boston Common Golf’s introduction was straightforward and professional and mirrored a press conference you would see from any other sports league. In a vacuum these pieces are not thorny, except there is no indication or winks that fun is at the forefront of what this is supposed to be. Again, this is simulator golf, which is not far removed from being a video game.

The format is a 15-hole fusion of foursomes and singles matches and feature two teams of three players. Meaning each player will hit just a dozen shots per match, and with only three players from each club, it certainly opens the door to the possibility that the marquee names aren’t always guaranteed to play.

The result is a format that can come off as contrived, and as the litany of past golf exhibitions have proved, there is little appetite for contrived matches. Then there are the teams. Well, what we think are the teams. So far, just three of the six have been given names beyond their cities, and only one (Boston) has announced its full line-up. Again, this league is supposed to be eight weeks away!

TGL made the teams regionally centric, which in theory is smart… except by using regionality to build fan bases, the league has disenfranchised fans in other markets from building equity with a club. And it’s not just those in the United States who live west of Atlanta and east of San Francisco and Los Angeles, as there’s no global flavour to it. Also curious: these teams will not be playing in any of their named cities, as all TGL matches will be contested in an indoor arena in Palm Beach, Florida, raising the question of why provinciality is used at all. The majority of players do not have relationships with their associated cities; three of Boston’s four players are international and Justin Thomas, who was born in Kentucky and went to university in Alabama and lives in Florida, is the captain of Atlanta. Confused? So are we.

Fuelling the confusion is the TGL PR strategy, announcing tidbits about the league every other day rather than letting the fans know exactly what they are getting into. Fair or not, the gradual release of information has led to the optics of disorganisation and that TGL is making this up as it goes. Add it up—the goofy team constructs, a handful of stars with non-household names, unimaginative formats, conflicting and over-serious tones, the piecemeal announcements… sound familiar?

There’s no need to relitigate the many missteps of LIV Golf over the past two years. However, one of the central reasons LIV has not gained traction with the golf populace is a failure to understand its audience, both in who that audience is and what that audience wants. LIV Golf insisted it was the hip alternative to the PGA Tour, that it could offer a fresh perspective on a product that had fallen into stasis. After all, the tour alone has 40-something tournaments a year, and the golf played each week looks mostly the same, with a self-importance that often seems unnecessary.

But instead of a re-imagination of what the professional game could be, LIV presented the same house with the same structural issues with a fresh coat of paint. Maybe a bigger problem: for all the things golf does well, cool is not one of them. And there’s nothing inherently cool about has-beens and never-wases dressed in clip art demanding to be treated like competitors instead of what they are, which is barnstormers. LIV Golf is a dad in a mid-life crisis, desperately trying to be something it’s not.

Which brings us to the biggest questions facing TGL: who exactly is this for?

Ostensibly it’s not for the fan who’s watching the tour week in, and week out. That’s fine, and probably good. In that same breath, what you’re presenting should likewise not turn off the base golf already owns, because that group will help spread the word. If TGL is an ambition to be something more than what the game offers, it could be falling into the same trap LIV fell into, which is not accepting golf is a niche sport. At times the game seems infatuated with growing its reach rather than appreciating and attending to the passion it already has. As for that untapped market, what about TGL will draw new potential fans in? The format is not radically different from the existing product of professional golf, and the players involved—while very good—simply do not own crossover appeal. As is, TGL seems like it’s caught in between two worlds without being a part of either.

The reason this is worrisome is TGL, in its most actualised version, could be additive to the sport. Disney is putting its weight behind the project, agreeing to air the competition on ESPN. That is a platform that can beget success to all invested in the game, from the professional level to the grassroots. One network source told Golf Digest that TGL has the chance to do for golf what the “Moneymaker Effect” did for poker. That comes across as hyperbolic, yet golf doesn’t get many chances to go mainstream and this could be one of those swings. It partially explains why powerbrokers such as Steve Cohen, David Blizter and the Fenway Group are a part of the financial backing, as well as celebrities such as Steph Curry and the Williams sisters: they think this thing could be big and want a part of the action. For golf, hopefully that’s true. However, a rebuke of TGL from general sports fans could deter future opportunities for golf-related endeavours, to say nothing of potential media deals coming down the pipeline.

Golf enjoyed a revival from the pandemic and renewed curiosity from Netflix’s “Full Swing” docuseries, yet TGL could be the vessel that proves if that interest has staying power. That is a sober assessment of a supposedly frivolous thing, which, it bears repeating, is golf played on a simulator. But despite its unserious construct TGL is treating itself seriously and it appears others have followed suit, and that could be a serious problem.