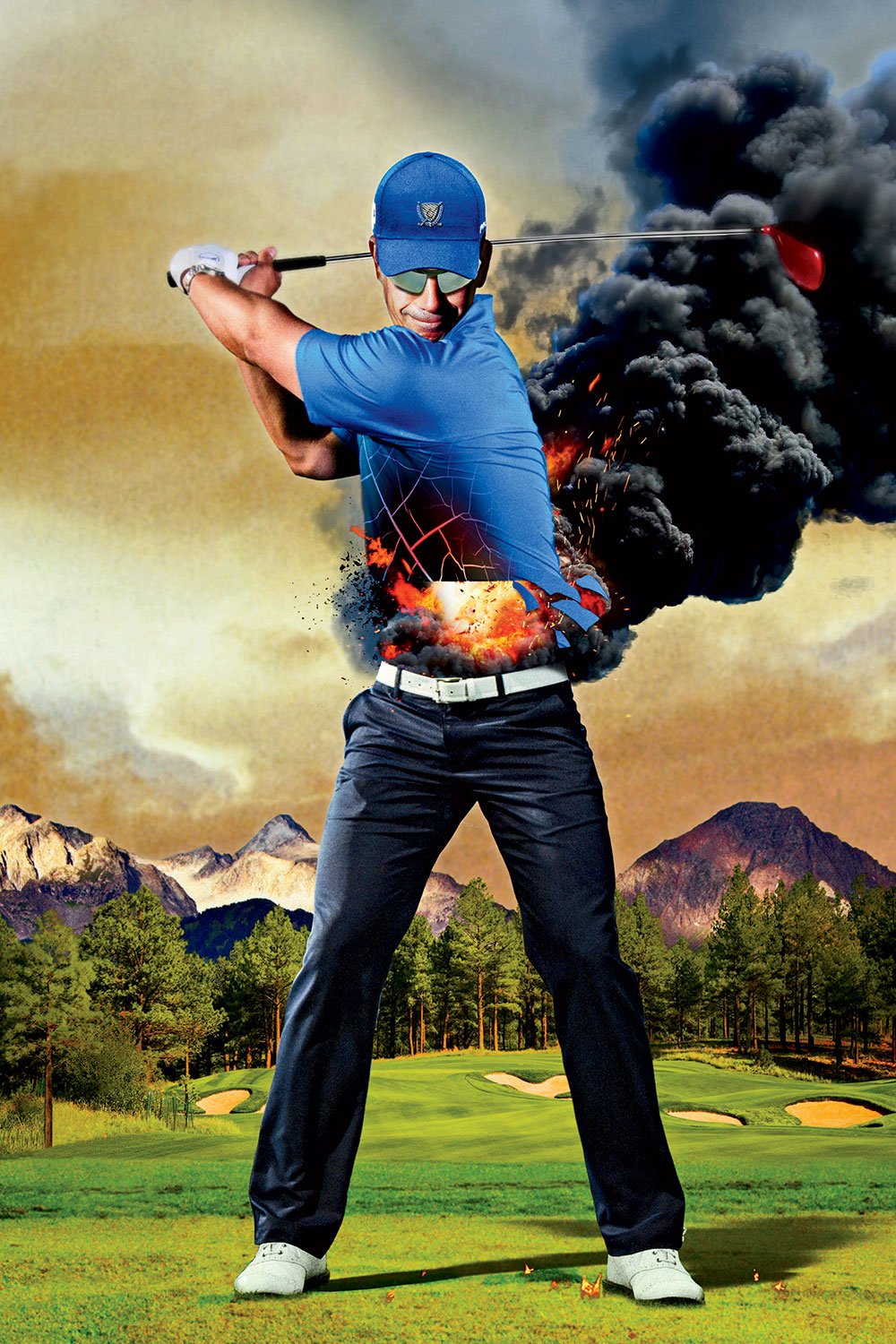

THE courses, clubheads and pay cheques are bigger, but the most obvious change to pro golf in the 21st century? The way the players look. Billowy clothes and dumpy physiques have been all but shamed off the world’s tours, with even the formerly portly profile of senior golf streamlined by the agelessly trim Bernhard Langer. Where was the image of a generic tour pro remade? The gym.

It used to be that genetic gifts were almost wholly responsible for why physically magnetic stars like Snead, Palmer and Norman stood out. But the current era is marked by a new army of clones who are clearly buffed under their stretchy shirts and skinny pants. All the lean muscle is accepted as indispensable for the power game now considered vital as the most efficient path to tour success. To get that way, at least some fitness training – but more commonly, a lot of it – has become mandatory.

It would be hard to argue that the results haven’t been a net positive for the game. On the modern pro tours, ball go VERY far, and the athletic and stylish image of the players is more marketable. Substantively it seems irrefutable that there are more golfers capable of winning tournaments than ever.

But to apply a Newtonian concept that is one of the foundations of the call for increased tour-pro fitness, for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. And what seems to be an emerging pattern – or perhaps just an aberration – has spurred some traditionalists to voice their latent scepticism about the new order.

But to apply a Newtonian concept that is one of the foundations of the call for increased tour-pro fitness, for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. And what seems to be an emerging pattern – or perhaps just an aberration – has spurred some traditionalists to voice their latent scepticism about the new order.

Why, the old-schoolers wonder, has it been that since 2000, the very players identified as the best and most physically developed have been so often injured? The names on that rhetorical marquee: David Duval, Tiger Woods and, most recently, Rory McIlroy and Jason Day.

The shorthand, which ignores some vital details, is this: all four were or are power players who made it to No.1, and all four transformed their bodies to a startling extent – especially their upper bodies – through intense training programs. In the case of Duval and Woods, the injuries were part of a precipitous decline, and in the case of the latter two 20-somethings, some recent downward slide has taken place. Bottom line, the more taxing workouts seemed to make all four more physically fragile.

It’s a simple narrative, and video posts of the impressively ripped current No.1 Dustin Johnson and US Open champion Brooks Koepka engaging in heavy-lifting sessions can look like harbingers.

Of course, all areas of Woods’ epic and perhaps tragic story remain a dominant and irresistible reference point in the game. Golf’s commentators know controversy will be sparked by any comparisons to Woods’ history of fitness obsession and injury. Early last year, a few months after McIlroy had been supplanted at No.1 by Jordan Spieth and Day, Golf Channel’s Brandel Chamblee went there when he cited Woods in respectfully expressing doubt about McIlroy’s direction.

“When I see the things he’s doing in the gym, I think of what happened to Tiger Woods,” Chamblee said. “And I think more than anything of what Tiger Woods did early in his career with his game was just an example of how good a human being can be; what he did towards the middle and end of his career is an example to be wary of. That’s just my opinion. And it does give me a little concern when I see the extensive weight lifting that Rory is doing in the gym.”

The year before, when McIlroy was No.1, Duval, who was transitioning to the television booth, referenced Woods and himself in seeming to issue a warning to McIlroy, telling reporters, “It looks to me the majority of the guys that get hurt, including myself, are guys that hit the gym hard and did stuff.”

McIlroy, who admits that second-guessing of his workout program is a “pet peeve”, responded to Chamblee and other critics by posting an in-your-face video of himself doing a set of three full squats with 120 kilograms, with the comment, “I’m a golfer, not a bodybuilder.”

McIlroy later explained that the motivation for the aggressive workouts that transformed him from underdeveloped adolescent to an Adonis was not about ego, but pragmatism. McIlroy’s unique combination of small frame, flexibility and an ability to generate incredible clubhead speed were all a recipe for further injuring a lower back that had begun giving him trouble as a junior. The antidote was a regimen designed by his British sport physiologist, Dr Steve McGregor, which strengthened the core and lower body and added upper-body muscle mass to help McIlroy’s swing become more stable, compact and powerful. “Rory absolutely did the right thing for him,” says venerated golf-fitness instructor Randy Myers.

Power VS Feel

But as we’ve learned in politics, wonky specifics don’t always penetrate the zeitgeist. There are various reasons weight training and golf remain a counterintuitive fit to many. The suspicion by sports cynics that the hardest weight-training workouts might be fuelled by performance-enhancing drugs invites criticism. Also, five-time NFL Super Bowl champion Tom Brady, uncut and relatively scrawny but better than ever as he hits 40, is strongly endorsing muscle pliability and suppleness over bulk.

Many general-interest sports fans continue to resist considering pro golfers real athletes. Even old tour pros can undermine such cred, as stalwarts from previous eras who never did a plank have a hard time buying into the power game when clichés like “the woods are full of long hitters” still resonate in their heads. Weights are particularly anathema. Gary Player was so far ahead of his time with his lifting regimen that he was still being derided in 1978, after he’d won his ninth Major. In the next decade, workout fanatic Greg Norman also got some funny looks.

After winning the British Open at Royal Birkdale in 1976, Johnny Miller bought a ranch and began doing heavy manual work to refurbish it. Over the next few months, Miller put on a dozen well-proportioned kilograms. When he rejoined the tour in 1977, he was suddenly a much worse golfer.

“It was like I was built like a tight end – broad shoulders, small waist, big legs,” Miller says. “I looked great, but I didn’t do any stretching, and I felt stiffer. When I went out and started practising again, my swing had lost a lot of flexibility. The worst thing was how far off I got with the distance control on my irons, which was the part of the game where I was better than anyone. I was hitting shots I had never hit before, flying it over greens, leaving wedge shots way short. Changing my body, putting on all that muscle, getting stronger but losing flexibility, it was one of the things that killed my game and probably caused a lot of my later injuries.

“Moderation is the best guide,” Miller says. “Sometimes guys who work out hard start looking in the mirror and fall in love with what they see. I think a golfer has to have enough strength and flexibility, but not go crazy with it.”

Many traditionalists have a soft spot for all the doughy players who had funky low-speed swings but could perform under pressure and, by the way, never seemed to get hurt. The quality most prized was not power but feel, as evidenced by the two-finger handshake favoured by Billy Casper, Chi Chi Rodriguez, Raymond Floyd and Lee Trevino so that precious digits wouldn’t get unduly squeezed. As a general rule, tour pros avoided strenuous exercise, knowing that in golf, compensations forced on the body can affect a swing groove, making even little injuries effectively big injuries.

Nick Faldo, who won his sixth and final Major in 1996, is perhaps the last truly great precision and touch player. Though he always kept himself fit – as a young man through cycling and today, at 60, retaining a gym habit – he has stayed away from barbells.

“I realise there is science and more knowledge today,” Faldo says, “but to me, messing around with weights of 200, 300 pounds, it doesn’t make sense when you’re playing a game of feel with a club that weighs only ounces. And when players change their bodies dramatically, whether getting bigger or smaller, a lot of times it hasn’t turned out well. We golfers can be delicate beings.

“I know the young players have a new style where they snap their body upward to hit it stupid long,” Faldo says, “but I still have doubts that method holds up on Sundays when they’re nervous. It still comes down to being able to land an iron shot on the yardage number and getting approaches within a 15-foot circle. Especially in the Majors, it’s still about nerve and touch. You know, I doubt Shakespeare mucked out stalls right before picking up his quill. I’m prepared to be proven wrong, but it just seems there’s another chapter to be written in this argument.”

Trainers have their say

All right, golf’s weight-lifting sceptics have had their say. To the trainers who actually work with tour pros – frustrated that their methods are still so often questioned – there really isn’t much of a debate.

Dr Ara Suppiah, an expert in functional sports medicine and the 2016 US Ryder Cup team’s physician, unloads when given the floor. “What critics are saying is not science, just anecdotal observation from a very small sample size with many variables,” he says. “For every golfer who has been hurt or simply accused of being hurt in the gym, I can name many top players – Henrik Stenson, Adam Scott, Sergio Garcia, Jordan Spieth – who work out regularly but have never been injured. The critics of pro golfers have it backwards. They say the gym work causes golfers injury, but today’s players and their trainers know firsthand it’s the sport itself that causes injury, and that they train to keep from being injured.

“Athletes in other sports get hurt, yet we never say they shouldn’t be in the gym,” Suppiah says. “But we say it about golfers. You would never say Rafa Nadal’s arms are too big. But we constantly say these things about golfers.”

Suppiah’s argument is that pro golf has evolved into a more athletically demanding sport. Much like major-league baseball pitchers throwing 95 miles per hour or faster who seemingly get injured more often, or tennis players with more powerful racquets getting injured from swinging harder, golf’s now-common 120-mile-per-hour clubhead speeds put a significantly heavier load on the body. “The equipment advances have allowed the body to go so much faster,” Suppiah says. “Because the driver can be set up for a one-way miss, and because it’s lighter and more forgiving, swings can be a lot harder without that much lost accuracy. Those conditions cause speeds and distances we’ve never seen before, but it takes a greater physical toll.”

Suppiah is a defender of Day’s aggressive fitness program, which the Queenslander said he stepped up in 2014 to prevent injuries that had plagued his early career. But much like McIlroy, Day is small-boned, generates great speed, is highly flexible and has a troublesome lower back. The noticeable development of his upper body is intended to stabilise and shorten his turn away from the ball, which when it was longer caused a serious injury to his left thumb.

Athletes in other sports get hurt, yet we never

say they shouldn’t be in the gym.

But we say it about golfers

Suppiah says that golfers get wear and tear the same way most athletes do – from ground forces – and cites Newtonian law as the fundamental rational for training.

“Golfers are generating almost three times their body weight at impact in downward force,” he says. “The ground is going to impart that same amount of force in return, and the majority has to be absorbed by the human body. Being able to handle those ground forces involves weights and is an important part of athletic training.

“But that training is misunderstood,” Suppiah says. “When a golfer gets thicker in the arms or upper body, it’s not because he’s necessarily focused on that part. The workouts golfers do are mostly core, back and leg-dominant. But doing squats, the arms as well as the legs will get bigger because growth hormone and testosterone is being released. The goal of a proper program is balance. And the only time the arms or legs get too muscular is if there is an accompanying loss of functional range of motion. I don’t believe Jason or Rory suffered that at all because of their workouts.”

Myers, the director of fitness at Sea Island Resort in Georgia, where he coaches Davis Love III, Zach Johnson, Brian Harman and Billy Horschel, is the author of the just-released book Fit for Golf, Fit for Life. He rarely makes heavier weight training the focus of programs he gives his players. “There has never been a study that says that by doing these powerlifting moves, I’m going to improve my golf performance,” Myers says, “but there have been studies that say if I get in better shape and I remain supple, I’ll be able to extend the length of my career.”

Myers prioritises his player’s longevity – “taking full advantage of golf’s extended lifespan and money-making opportunities” – over performance. “I think it’s significant that Tom Brady has adapted a lot of golf principles in the way he trains,” he says. “Our golfers actually train a lot like quarterbacks. We want their muscles to be pliable. The swinging motion is very similar to the throwing motion. You need strong legs, a very strong core and suppleness in your shoulder joints and mid-back. The guys who have been able to stay out on tour longer aren’t the most muscular and, in most cases, not the strongest. But they’re the most supple, with a high range of motion, flexibility and symmetry.”

Myers believes that a player following his principles will actually improve his touch: “By improving posture and balance through core strength, it’ll be easier to keep the body still during chipping and putting.”

‘Golf Fitness is really still in its infancy’

At the same time, Myers says golf is behind other sports in fitness coaching because it lacks full acceptance by players, and there’s a relative lack of documentation about cause and effect. Myers remembers meeting Player, then in his 60s, in the 1990s and hearing the Hall of Famer confess that he wasn’t sure what part of the lifelong regimen he had so diligently followed had actually been advantageous for golf. Norman, an early adherent of intense exercise who tried to improve on Player’s example, now admits that if he had done things differently, he might have avoided some of the surgeries he faced late in his career and after his retirement from competition. “Golf fitness is really still in its infancy,” Myers says.

Joey Diovisalvi, who trains Johnson and Koepka, believes that although golf-fitness knowledge is accelerating because of the increased needs on tour, more mistakes are possible because players are pushing harder than ever to gain an edge. “Injures are more common than ever because players are more aggressive and they’re not afraid to do the things that they have to do to perform,” says Diovisalvi, known as Joey D. “It doesn’t mean they’re smart enough or diligent enough to do the proper prep work.” Diovisalvi poses the question, “Did Tiger do things that were potentially rogue?” referring to accounts of Woods’ Navy SEAL-style training and performing exercises like technical Olympic-style lifts with extra weight that went against the advice of his then-longtime trainer, Keith Kleven. “He could have.”

Diovisalvi sees a need for improvement in the field in preconditioning golfers for challenging workouts, and in understanding the proper recovery protocols to lessen injury. “When players come back from being hurt or fatigued, sometimes they’ve given themselves their own green light, and they return too soon,” says Diovisalvi, whose first clients when he began helping tour players were Jesper Parnevik and Vijay Singh. “I don’t know if we’ve done a great job in golf getting players to understand that proper recovery simply takes time. You start to realise that, left to their own judgment, recovery is not something they do well.”

The argument runs counter to the criticism that current players often get for skipping too many tournaments. The basis is the relative ironman schedules that were common, especially among journeymen, in previous eras. But Jack Nicklaus – and later Faldo and Woods – showed the effectiveness of a shorter schedule designed to peak for Majors.

More than ever, many of today’s players have the economic luxury of waiting until they’re mentally eager and physically primed before embarking on a string of tournaments. Given that those choices are now more complicated because the more extensive worldwide tournament schedule effectively lengthens the playing season, fitness trainers, Diovisalvi suggests, should strongly encourage a pace modelled on the way horse trainers hold out prize thoroughbreds to run only when they are fully rested, and preferably for the biggest races.

‘To say that PEDs don’t exist in golf, I don’t believe that’

Diovisalvi also sounds a warning that increased training by golfers brings with it the possible use of performance-enhancing drugs.

“We have to get a hold of that in golf,” he says. “I don’t believe it’s as common as in other sports, but I would never doubt that it’s going on. Some guys will take the risk because the financial temptation pushes them beyond their ability to think rationally.

“To say that PEDs don’t exist in golf, I don’t believe that. When they start blood testing [in this new 2017-’18 PGA Tour season], we’re going to see a whole different dynamic.”

As Faldo says, there’s another chapter to be written on the role of fitness in golf. It will likely be one in which trainers will have a more definitive handle on the proper protocols.

“We all relish those moments when a great athlete pushes the limits of what a human being can do, and it’s a thrill to be part of that,” Suppiah says. “But more and more, for every one of those moments, even in golf, the athlete will be on the edge of being injured or breaking down. Could be through a training regimen, or intense practice sessions, or on the edge of mental exhaustion. That’s what the greatest athletes do, and what the new demands of golf are making the greatest golfers do. The athletes will always want to go there. It just means that in golf, the trainers who can properly guide them will become even more valuable.”