The 50-year-old hopes to redefine his career and image on the PGA Tour Champions.

Photographs by Jensen Larson

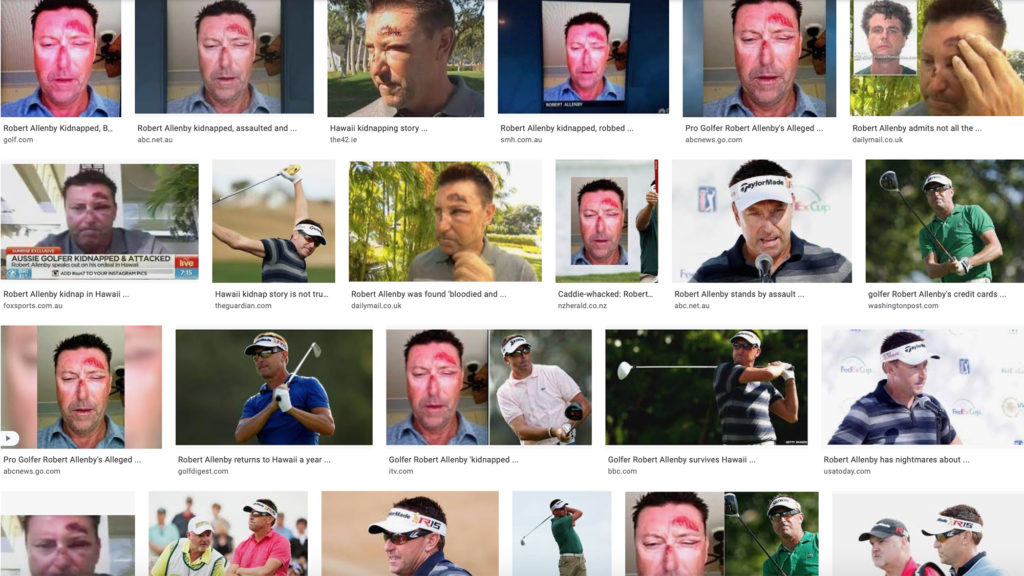

Robert Allenby knows what appears when you Google his name. His 21 victories worldwide don’t show up, nor does a PGA Tour résumé of four titles and $US27 million in career prizemoney. Instead, photographs from the Victorian’s incident in Hawaii in 2015 are the top result, accompanied by a kidnapping story even he admits “sounds like the movie ‘Taken’”.

More than seven years on, Allenby cannot escape the story that once made headlines. “Even now when I play golf, sometimes I hear people say, ‘Oh, that’s Robert Allenby. Did you see what happened to him in Hawaii?’”

The saga began on January 16, 2015, when Allenby missed the cut at the Sony Open. He went drinking at the Amuse wine bar in Waikiki with his then-caddie Mick Middlemo and good friend Anthony Puntoreiro, whose business was securing short-term sponsorships for golfers and tennis players. Allenby put his glass down to take a photo with a group of Australian fans, and that is when he believes his unattended drink was spiked with Rohypnol. What happened in the next two-and-a-half hours after Allenby left the bar is a mystery. The next day Allenby said that he had been drugged and kidnapped, thrown into the boot of a car, beaten, robbed and dumped back where he was taken from. His credit cards, wallet and phone were missing.

The void between what we know about Allenby’s story and what we don’t is why it is as intriguing now as it was then. We know Allenby’s credit cards were stolen by Patrick Owen Harbison, 32, who had five previous convictions, including one for drugs. Harbison used the cards to buy top-shelf liquor, clothes and even macadamia nuts – a shopping spree totaling $US20,000. He went to jail for five years for credit-card fraud. John McCarthy, the lead investigator of the Honolulu Police Department in 2015, had seen it many times. “They buy items they know they can get a good resale value for,” he says. “By the types of items Harbison bought, you could tell it was a homeless person.”

Initially, it was misreported that Allenby went to the strip club Femme Nu and spent $3,400. A Golf Channel article cited unidentified sources, and later it was removed from the website. “That definitely ruined the character of Robert Allenby,” Allenby says. “Mentally, that really hurt me a lot.” McCarthy confirmed with the club’s manager that Allenby was never there. “I think those reports were really unfair,” McCarthy says. “He got a bad deal.”

But what we might never know is why Allenby woke up in a park at about 1am on the Saturday with his face bloodied and injured, one block from the Amuse wine bar. He was found by a homeless woman. Allenby maintains his drink was ‘roofied’ inside the bar and that he was assaulted outside it.

“I told Puntoreiro I was going to the bathroom, and that was the last of it,” Allenby says. “Outside, I remember this guy, and he just went bang [punch] right between my eyes. Then they dragged me out. They took what they wanted off me and dumped me out in the gutter, and that’s where I lay for the next three hours.”

Allenby never filed assault charges.

McCarthy says the most logical explanation for Allenby’s injuries is that he hit his head on a rock. Why he hit his head remains a mystery, McCarthy says. “We know he fell or tripped and hit his head. We matched things up with what people told us and his injuries, plus the rock. He said he was assaulted, but we just don’t know for sure. He could have been assaulted. He could have been hit from behind while walking down Kapiolani Boulevard or pushed or shoved, and then they took his wallet. You can tell when someone is lying, and [Allenby] wasn’t lying. Let’s put it this way… it’s greater than 50-50 that he was assaulted, but we can’t prove that.”

Later that Saturday, Allenby, whose phone was missing, posted a selfie of his facial injuries on Facebook from his iPad to alert his family back in Florida. Some golf-media figures saw the photo, and the story exploded. Allenby spent the next few days repeating to various worldwide news outlets that he had been kidnapped. But the kidnapping narrative was quickly called into question when the homeless woman denied it. Before he could get home from Hawaii to The Club at Admirals Cove in southern Florida, the security guards called Allenby and said 15 television crews were waiting outside the gates.

Staff in the clubhouse at Admirals Cove now greet Allenby warmly as he walks into the swanky establishment. Members come up to say hello, shake hands and ask how he’s doing on the PGA Tour Champions. He seems popular.

Allenby is content here – the club has 45 holes of golf, a restaurant bar that can be accessed by yacht through the marina and a hotel solely for members’ guests. One could go long periods without leaving the property, as Allenby did in the years after Hawaii. “I would often go several weeks without leaving the estate,” he says. “I didn’t want to be in public and have to deal with people saying negative things about me. I lost confidence in my golf. I lost confidence in myself. I struggled as a human.”

He was overwhelmed. He had nightmares of being chased down a street and sought help from a psychologist. “No one likes to be put down or made fun of, and it got to the point where I just wasn’t coping with it at all,” Allenby says, “so I went and sought help. It was a very low time. I had so much fear and anxiety built up inside me. It ruined my confidence to go outside and to be in front of people because I [believed] they were always talking about it.”

He went on antidepressants for six years, but the medication didn’t agree with him. “My insides were constantly in pain. If I tried not to take them, the headaches felt like someone was hitting me with a hammer. I finally got off them a year ago. I had to just stay inside the house for weeks and go cold turkey. I can tell you it was one of the toughest things I’ve had to do, but my body feels way better for it.”

The incident took a toll on wife Kym, son Harry and daughter Lily. Lily’s 13th birthday was that January 17, the day it all went public. Allenby recalls Lily crying on the phone when he was eventually able to call her. “It was tough and had a huge impact on them, seeing all these pictures of their father all over the news. There was a lot of negativity that rolled into Kym’s life because my life is her life. So we really just tried to stick together and pull through it.”

Despite all this, Allenby admits little culpability. “I’m not embarrassed about it,” he says. “I didn’t say I was thrown out of the [boot] of a car. I said I was told I was thrown out of the [boot] of the car. A reporter said, ‘It sounds like the movie ‘Taken’, and I said, ‘Yes, it does.’ Agreeing with him and what the homeless lady said to me compounded the story.”

Middlemo regrets how he fielded a phone call from Golf Channel on the afternoon of January 17. He had left the Amuse bar an hour before Allenby and relayed what Allenby had instructed him to say about the kidnapping, robbery and assault. “If I had my time again, I’d hang up the phone and talk it over with Rob and ask if he really wanted to comment on this just yet,” says Middlemo, who is now a restaurant owner in Atlanta and still caddies part-time for tour pros. “I don’t think anyone realised how much this was going to blow up. I don’t think we planned it out as a team. I was new to caddieing for Robert.”

Their relationship didn’t last long. Later that year at the Canadian Open at Glen Abbey, the pair had an argument sparked by a club selection, and Middlemo walked off the course mid-round. A Canadian school teacher volunteered to caddie for Allenby for the remainder of the round. He shot 81 and withdrew. When reporters at Glen Abbey asked Middlemo about the events of Hawaii six months earlier, he suggested Allenby had simply fallen over and hit his head. “It was maybe an emotional reaction, and I regret some of the things I said, but not all of them,” Middlemo says.

Allenby has a mixed reputation among caddies, having hired and fired many. One former caddie tells the simple yet illustrative story of when he once suggested an 8-iron for an approach shot at a tournament. Allenby responded, “It f—ing better be an 8-iron.”

Allenby has had friction with players, too. After losing to American star Anthony Kim in singles at the 2009 Presidents Cup, Allenby said Kim had been out until the wee hours of the morning instead of preparing for their match. At the same event two years later, he got into a spat with fellow Australian Geoff Ogilvy about who was to blame for their match loss during Saturday foursomes at Royal Melbourne.

Justin Leonard is one year younger than Allenby, played in the 2009 Presidents Cup and made the cut that notorious weekend in Hawaii. He suspects that perhaps another player would have received more benefit of the doubt. As Leonard says, “I think because over the years and because of Robert’s personality, he probably, you know, maybe pushed a few people away, maybe stepped on a couple of toes, and so it was likely some of that affected how people viewed what happened.”

Stuart Appleby has known Allenby since their junior golf days in Australia. “Robert has matured and mellowed a lot, but there’s a youthfulness to him. He likes a drink and a party. In his 20s and 30s he had the capacity to live the high life and have a great time and still play great golf,” says Appleby, who was going to bed much earlier. “He had all the talent in the world but couldn’t recognise he needed to be the CEO of the company and take responsibility. If you don’t want to be the CEO and run this company, you’re going to try to dish it off to the next in line, which often was a caddie. But there are plenty of guys on any tour in the world who have big hearts and they’re generous, nice people that can simply be nightmares to work for.”

Evidence of Allenby’s soft side can be found in his charity work. He has helped raise more than $20 million for the Challenge Foundation, which supports children with cancer and their families in Australia, through an annual golf day and gala. Allenby’s close friend, 1991 Open Championship winner Ian Baker-Finch, struggles to reconcile how different Allenby can be outside the ropes. “I can’t explain it, mate; it’s just his competitive nature I think,” says Baker-Finch. “Rob has always been a sweetheart. I think when he entered the carpark of a golf tournament, he changed. At the end of the day, he is disappointed in himself that he never reached the heights he thought he would and that we all thought he would. We all thought he’d win Majors, for sure. He was a similar age to [Major winners like] Retief Goosen, Ernie Els, and Michael Campbell.”

Asked how he has grown since 2015, Allenby says that he has learned to keep a closer inner circle. But for the highs and lows of his career, Allenby recognises he is ultimately responsible. “I’ve had a lot of ups and downs, and 100 percent I’ve caused those ups and downs. I’ve been very boisterous. I’ve always said it as I’ve seen it.”

Allenby made more than a half-million dollars in prizemoney in 2014, but after the Hawaii incident, his career entered a freefall where he didn’t make more than two cuts in any season on the PGA Tour. One of the inspirations for Allenby to ween himself off medication was becoming eligible for the PGA Tour Champions when he turned 50 last July.

As much as he is trying to create a new chapter, on occasion a spectator will remind him of the previous one. “At the Senior British Open at Sunningdale last year,” Allenby says, “someone said, ‘Oh, that’s Allenby. He was an amazing golfer, but man that Hawaii thing just ruined him.’ When my caddie heard that, he said, ‘Are they still talking about that?’ What can I do? People are allowed to have their opinions.”

On the PGA Tour Champions, Allenby has not played good golf thus far while dealing with multiple injuries. He massages his back while explaining his ailment. “I had a nickname during my days in Europe in the 1990s. Friends on tour would call me ‘Guinness”, because I didn’t travel well,” he says.

Still, Allenby is hopeful he can turn his Champions tour form around and win a senior Major championship, given that he was not able to win one on the regular tour. Allenby won four events on the PGA Tour – including the prestigious Western Open – as well as the Pennsylvania Classic in what was the PGA Tour’s first event back after September 11. In 2005, he won all three of Australia’s biggest summer golf tournaments – the Australian Open, Masters and PGA – the only golfer to ever achieve that feat in the same year. But Allenby’s record at the Majors was unsatisfying – his best results were a tie for seventh at the US Open and again at the Open Championship. He had a couple of non-threatening top-10s at the PGA Championship and never registered a high finish at Augusta National.

“I’d like to say a senior Major would be as satisfying as a regular Major, but I don’t know,” he says. “The real Majors are the real Majors. There are only four. I’d have to go win a senior Major and let you know what it feels like.”

Allenby, though, is just happy to be playing golf again after a roller-coaster seven years. “The chance to go out there and compete again is pretty cool,” he says. “There aren’t many jobs that offer you a second chance.”