THE FIRST TIME I met Pete Dye, he was in the midst of doing something he relished more than almost anything else: watching professional golfers suffer. We were standing behind the green at the long par-3 17th hole at the Ocean Course at Kiawah Island a few days before the start of the 1991 Ryder Cup, otherwise known as “The War by The Shore”. (It was actually a two-front war: the Americans versus the Europeans, and everyone against Dye’s punitive new design.)

A foursome of American players was on the tee. No one hit the enormous putting surface measuring about 10,000 square feet. Two of the four players found the eight-acre pond that covered the distance from tee to the offset green. Pete wore a huge grin as he turned to face me. “That seems about right,” he said, a noticeable gleam of mischief in his eyes.

I thought of that day with a sense of melancholy after hanging up the phone from his wife, Alice, earlier this month. It was my habit to call my fellow Ohioan every year or so to catch up on his latest design work and get his take on current events in the game. In this instance, I also had a question for him about one of his more celebrated layouts, The Golf Club in New Albany, Ohio.

Pete couldn’t come to the phone, Alice said, because he was playing golf at The Little Club near their home in Delray Beach, Florida. Then she apologised that there would be no return phone call. “He’s not really able to use the phone much anymore,” she said quietly.

Her next few words were devastating.

Pete Dye, perhaps the game’s most transformative course designer, has been stricken with Alzheimer’s. It’s the cruellest of ironies that Dye is fit enough at age 92 to play golf most days but no longer can articulate the ideas that altered the rubric of golf course architecture.

Pete Dye, perhaps the game’s most transformative course designer, has been stricken with Alzheimer’s. It’s the cruellest of ironies that Dye is fit enough at age 92 to play golf most days but no longer can articulate the ideas that altered the rubric of golf course architecture.

“It’s such a tragedy that such a wonderful mind is being lost,” said Alice, who has been his faithful sidekick on a number of his works, including the renowned Stadium course at TPC Sawgrass, during their 68 years of marriage. She couldn’t muster any more words except to say, “you should talk to the boys”, meaning their two sons, Perry and P.B.

The golf architecture fraternity has known for a while that the Dye family has been suffering in silence as the disease has progressed. “Pete really hasn’t been Pete for some time,” said Dr Michael Hurdzan, another Ohioan who has enjoyed Dye’s friendship for years. “What a shame that is, to not only lose the person but also all those ideas. And let me tell you, they were revolutionary.”

“It’s the end of an era,” added Bill Coore, who worked for Dye for three years and is now enjoying a sensational run partnering with former Masters winner Ben Crenshaw. “Before Pete came along, golf architecture was Robert Trent Jones and that philosophy. That was the standard. Pete took the game and design in a different direction.”

The onset of the illness wasn’t noticeable until mid-2015, at The Golf Club, of all places – the layout that brought him his first accolades and where he initially introduced railroad ties to American golf architecture after he and Alice ventured abroad to study the courses in Scotland. His younger son P.B, who assisted Pete on the renovation of the greens, detected slight changes in his father’s ability to communicate. Since then his faculties have declined steadily. But one thing brings him around, igniting a visceral reaction that restores a bit of who he is, and that is the game. “There are moments of brightness, and it’s when he’s walking down a fairway,” Perry said. “And whether he mumbles something or draws something up or just is standing there and looking at a golf hole, it’s kind of the best he can be anymore. Something kicks in.”

“You put my dad on a golf course, and he goes into a different mode,” P.B. added. “He knows how to hit the golf ball and can shoot a pretty decent number from the forward tees. It’s almost like he sees things differently on the course. But once he leaves, he doesn’t know what golf course he played or what he shot. He might not remember who he played with. But on the golf course, he enters a world he knows.”

“You put my dad on a golf course, and he goes into a different mode,” P.B. added. “He knows how to hit the golf ball and can shoot a pretty decent number from the forward tees. It’s almost like he sees things differently on the course. But once he leaves, he doesn’t know what golf course he played or what he shot. He might not remember who he played with. But on the golf course, he enters a world he knows.”

Maybe that’s because it’s not only a world he has felt and touched since he was a boy, but it’s also one Pete Dye has conjured time and again from inside his head. Golf is second nature to him, as automatic and reflexive as breathing.

Whatever it is, golf still brings a smile to the old man’s face, alights something in his mind, perhaps taking him all the way back to Urbana, Ohio, where his father, Paul (Pinky) Dye, built a nine-hole course himself on some family-owned farmland after a Scotsman with a more accomplished pedigree turned down his appeal for help. Donald Ross was in the midst of designing nearby Springfield Country Club and couldn’t spare the time. When America was drawn into World War II, Pete for a time served as the greenskeeper of his father’s pride and joy, Urbana Country Club. He had been digging answers out of the dirt since a young age and had become a fine player, but around this time he discovered in him the burning desire to carve new questions into it, too.

The results speak for themselves with masterpieces such as Harbour Town, Oak Tree National, Whistling Straits, Crooked Stick and, of course, TPC Sawgrass.

Sadly, we have seen his last inspired creation. All that remains is a residue of knowhow that enables him to still derive some enjoyment from the game.

“About 18 months ago we played golf together, and I knew he was starting to struggle,” said Tim Finchem, the former US PGA Tour commissioner. “But here’s the thing. Golf was still in there. I played with him at Gulfstream. He was one-over par on the back. He’d hit a tee shot and ask, ‘Where’d it go?’ It’s in the middle of the fairway, Pete. He’d hit another shot. ‘Where’d it go?’ Middle of the green, Pete. He made everything he looked at almost. It was incredible.”

Bobby Weed, who has worked with the Dyes for nearly 40 years, spends more time with Pete than anyone except immediate family. Weed sees the golf course as a sanctuary for his mentor, someone he considers his second father. It’s a sanctuary of discovery. Or a rediscovery, as it were, of himself.

“It’s all about just engaging him, about exercise and therapy, and golf is the best and easiest way to do that,” said Weed, who has a particular understanding of special-needs individuals; his daughter, Lanier, is autistic. “Recently we went to Old Marsh, and that was maybe the first time that he did not play, and normally he will play. But, still, he embraces the game, and it’s clear how much he still connects with golf. It’s a comfortable atmosphere for him to be on a golf course. We’ll go to his courses – Old Marsh, Dye Preserve. We’ll talk about a certain feature on the course, and he’s with me on that. I pepper him with questions and get him thinking. Some days, obviously, are better than others. Every day on the golf course is good for him. Some days he knows me. Some days I’m not sure. But that’s the challenge of Alzheimer’s.”

There is still a need today for the radical genius of Pete Dye. He has designed nearly 200 golf courses, and many require upkeep and renovation to prevent them from falling into obsolescence. His sons, successful course designers in their own right, have inherited the duty, and it is an agonising burden, because that’s when it hits home hardest that the most vital aspect of their father, his unique intellect, is extinct, even as the man himself soldiers on in relatively good health.

“My brother and I, we’re trying to keep abreast of 200-some golf courses. You feel responsible for the next generation of golf and what is happening with these courses,” Perry said. “We have strong feelings about his classical work that has been antiquated. We understand how he thinks, but we’re not him. He’s getting robbed here at the end. All of us are.”

“When we were in New Albany, and I was there 85 straight days, a very strong part of me was saying, ‘This is like a Monet. How much do we really want to touch it?’ It’s not an easy question to answer, and we’ll be facing those questions again and again,” P.B. added.

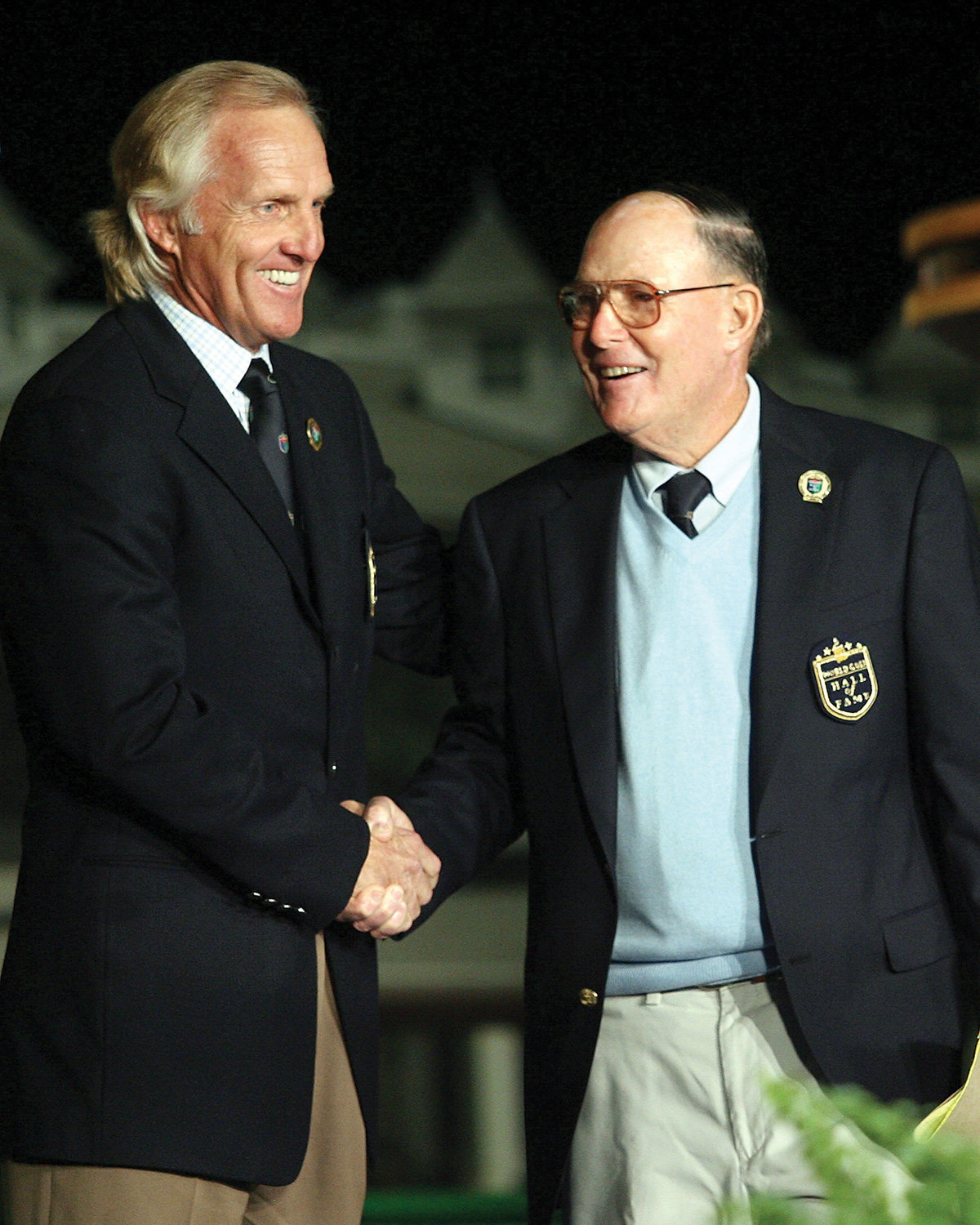

What is without question is Pete Dye’s inimitable place in golf. Dye is one of only four golf course architects enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame. His ideas, while rooted in traditional architecture, produced a new-age body of work that has challenged players in all new ways.

“First and foremost, Pete is such a unique individual who has added an awful lot to what makes the game of golf what it is; he’s one of the funniest guys you ever want to be around,” Finchem said. “He’s a beautiful man who is loved dearly throughout golf. I don’t think there’s any question he has been an impactful person in the game of golf for years and years and years. He’s been relentless when it’s come to architecture, as well as golf course conditioning and agronomics. He understands how all of it fits together. It’s so important to the history of the game that he has been a part of it.”

“My work will tell my story,” Donald Ross once wrote. Dye repeated that passage in his autobiography, Bury Me in a Pot Bunker, because that is how he preferred to be remembered. But Weed said there is more to his legacy than just golf courses.

“It’s not just what he and Alice have done with design, but what they’ve done behind the scenes for golf,” Weed said.

“Pete is going to have a number of legacies. His golf courses will stand the test of time. His other legacy is how many people he has influenced who themselves have contributed to the game or are part of the game, myself included.” – Bobby Weed

“My father will be respected most, I think, for loving the game of golf more than just about anyone ever has – in all forms,” Perry Dye added. “To play it, to build golf courses for it, and to promote it… that’s what he loved to do. He didn’t care much about anything else except promoting the game and bringing ideas to golf-course architecture that would help do that. I think that’s why the game, more than anything else, resonates in his mind most strongly. It’s just a part of him, and it will be right up to the end.”