Life – and golf – hasn’t always been straightforward for Mark Hensby, Australia’s latest winner on the PGA Tour Champions.

For better or worse, the true measure of one’s character is largely gauged by the direction a person opts to take at those crossroads before everyone at one time or another in life. Largely gauged, though, not entirely.

Equally as compelling is the quality of the conviction and sincerity which serve as the inspiration for those chosen paths. For as long as Mark Hensby can remember, there have existed challenging, almost blinding intersections.

Born in Melbourne in 1971, Hensby and his two brothers, Darren and Jason, grew up with their parents about five hours north of Sydney in the country-music town of Tamworth. When he was just a young lad, the boys’ parents divorced. Hensby’s formative years were emotional and challenging, complete with a host of unpleasant extensions that, by and large, have come to define his direction in life, personally and professionally.

“My dad was both mentally and physically abusive,” Hensby says. “It was to an extreme that people wouldn’t understand. To go home every afternoon thinking something bad is probably going to happen is a hard way to live as a kid. I took it upon myself to make sure I wasn’t home very often.”

According to Hensby, what began as emotional abuse soon turned very physical. When they became teenagers, the severity only got worse.

“I just didn’t understand,” Hensby said. “And, to this day, I still don’t.”

More than he feared for himself, Hensby felt sorriest for his older brother, Darren, who caught the violence worse than his brothers.

Hensby’s life with his father was so volatile, in fact, that his daily routine included leaving the house before his father, who worked nights, got home. His usual escape from what is supposed to be one’s safe place started each morning at 4:45, just prior to his father’s 5am return home. At the other end of each long day, with one exception, Hensby would not return home for the night until his father had left for work.

“I did have to be home for dinner,” he said. “If I wasn’t, the repercussions were pretty bad. So, yeah. It was definitely not the picture-perfect childhood, that’s for sure.”

When the sanctity of his own home proved to be anything but a safe haven, Hensby sought diversions at every turn. As a pre-teen, he stumbled onto an unlikely activity that provided desperately needed respite.

“I was 12 years old when I first played golf,” Hensby recalls. “Me and a kid up the street I played rugby with one day said, ‘Let’s go play nine holes of golf.’ We both laughed, like, ‘Play what?’ But we did it. We went and played nine holes. And that’s where it all started.”

Hensby began playing every Sunday, then every day. With his school within close proximity of the course, Hensby even began playing before and after school. “I practised, practised and practised” Hensby says. “I became obsessed with golf.”

Within two years of having first touched a golf club, Hensby was carrying a handicap of 3. Impressive growth by anyone’s measure. The impetus behind that rapid improvement, though, remained a sad one: fear.

“Now that I look back in time, I see that, yes, it definitely was [an escape],” Hensby said of his childhood home with his father. “But, in saying that, I had become obsessed with golf, too. So I think it was a perfect storm. I didn’t want to be at home, and I was obsessed with golf.”

Back then, Hensby recalled the club’s members as being anything but enthusiastic about juniors taking over the course and its practice facilities. From those complaints came the mandate that Hensby would be permitted to play and practise just once a week, on Sunday mornings.

In addition to practising and playing all he could as he ushered in his teenage years, Hensby drew a pay cheque by washing dishes and mopping floors at a nearby restaurant.

“That was a funny one, because I didn’t do it every night, just Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights,” he recalls. “I then got a second job as a postman, delivering mail. Thursdays and Fridays were a little tough, because I worked until 2am at the restaurant then had to be up at 5am, just a few hours later, to go to the post office.”

An escape path

Over time, golf became the source of those things that should have been encouraged and developed at home: confidence, comfort, belonging. When the quality of his game began to draw the attention of many, Hensby’s hope for a scholarship to experience college kept his drive alive. College would have provided him the chance to further both his education and golf game. More than anything else, though, it would have provided him somewhere to possibly find the peace he was never afforded at home.

“When you grow up, let’s say you have Tiger Woods on one hand, whose dad always told him he was going to be great and… well… then there’s the kid who is always being told he’s wasting his time and will never amount to anything. You get told that a million times and it’s definitely going to be a harder road.”

Hensby said playing golf in college was always on his mind. His concern, though, was that not many people knew about him because of where he lived. It wasn’t a major city which, Hensby says can be a handicap in Australia. He never received a scholarship.

By way of an American friend of an Aussie friend, Hensby was offered a move to Chicago in 1994. If willing to relocate to the Windy City, he was told, the friend’s friend was offering free lodging and even practice-facility access at famed Cog Hill Golf & Country Club. Hensby wasted little time making his decision of which way to go at that life intersection.

“I saved up my money with various jobs I was doing at the time,” Hensby says. “I was still an amateur, so I came over and gave it a shot.”

It wasn’t always easy for Hensby, though. One of the more dramatic stories that gained media traction centred on a period of – for lack of a more fitting term – being between homes.

“That has been exaggerated over the years,” Hensby insists. “I didn’t do it for three months [as reported]. It was just that, at times, there was nowhere for me to stay. The people I’d come over to stay with left and I had nowhere to go.”

As often as he could, Hensby would sneak into the upstairs of the clubhouse, where some of the staff stayed, to possibly find an unclaimed bed. Most nights, though, he was out of luck and ended up sleeping in his car in the Cog Hill carpark.

“When it got to wintertime, it got quite cold, so I’d have to drive around to warm the car up for a little bit,” Hensby says. “The range manager found me one really cold morning. My feet were almost frozen, so people helped me along the way and found me somewhere to stay. That was very nice.”

After winning the 1994 Illinois State Amateur the year he relocated to America, Hensby blistered the 1996 Illinois Open field by eight shots. Qualifying for what is now called the Korn Ferry Tour in 1997 paved the way to three wins on that circuit. On the strength of his second-place finish on the 2000 Korn Ferry Tour moneylist, Hensby earned PGA Tour rookie status for the 2001 season. After being relegated to the Korn Ferry Tour in 2002 and 2003, Hensby earned a return to the PGA Tour in 2004 after claiming his third and final Korn Ferry Tour title in 2003.

By that point, Hensby had covered a lot of ground, personally, professionally and emotionally. With each passing day, his resolve grew tougher. He drew as much strength and focus from the things that didn’t work out as he did from those that did. Rising above the trials and tribulations of his childhood resulted in a resilient and patient player.

At the BMW Championship on the PGA Tour in July 2004, Hensby finished equal third, three strokes behind winner Stephen Ames. Interestingly, it was to Ames that Hensby finished second at the Trophy Hassan II in Morocco on the PGA Tour Champions this February.

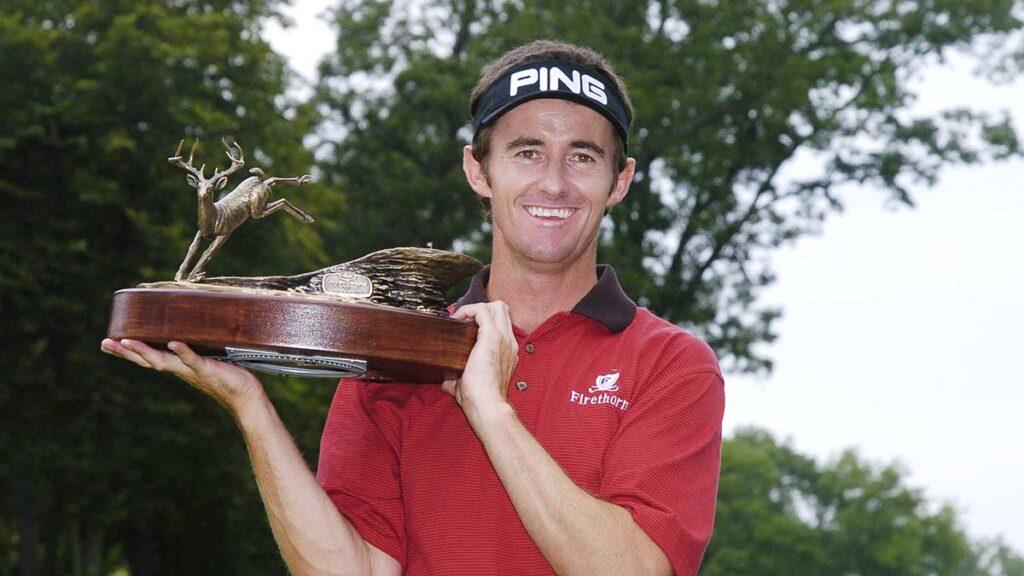

A week after that top-three finish in Chicago in 2004, Hensby took what he hoped to be good momentum to Silvis, Illinois, for the John Deere Classic. After making an ace on the third hole in round one at TPC Deere Run, Hensby overcame a four-stroke deficit beginning the final round with a five-under 66 to finish at 16-under 268 and tied with John Morgan after 72 holes.

On the second extra hole, the kid from rural New South Wales who had picked up the game as a means of self-preservation emerged victorious. In addition to being quite a handsome payday, validation for all his years of tireless, perhaps even stubborn, work had finally been reached.

“I think the John Deere Classic win did prove something,” Hensby says today. “I never played golf to prove anyone wrong or right. But there were a lot of naysayers. I proved to people that my hard work wasn’t a waste of time. It was nice to close their mouth.”

Highlighted by that victory in the Quad Cities area, a runner-up finish and two third-place showings, Hensby’s 2004 campaign landed him nearly $US3 million in earnings, more than double the amount he would make in any other season on any tour.

Things were looking up – way up. That banner 2004 season resulted in a position on the International squad for the 2005 Presidents Cup.

For his family

A year later, though, fate befell Hensby again. A car crash after picking up his son from school ended with Chase Hensby being air-lifted to hospital. Chase would make a full recovery, but his father’s return to form was more challenging than originally anticipated.

Although he was seemingly not too beaten up from the crash, Hensby found himself struggling upon his return to competition. The lingering and new pain were severe enough that he became unable to finish that 2006 season.

“I just remember how hard it was and how much work it took to get there,” Hensby recalls. “Then, for all of that to just disappear overnight was difficult. It was definitely difficult.”

Hensby and his wife, Kim, were married in 2009, after which time Caden, now 11, was born. Chase, Mark’s son from a previous relationship, was 11 when Mark and Kim married.

In 2017, when Caden was diagnosed as being on the spectrum of autism, Hensby’s commitment to his family and son never wavered. He began educating himself on the inner workings of his son and learning a lot about autism.

“He’s a great kid,” Hensby says. “He’s a love of my life. He’s intelligent and has come a long way from where he was five years ago with all the help. All kids are special, but I think kids on the spectrum of autism are so special.”

Mark and Kim opted to proceed with his educational experience at a traditional school. What the couple experienced, though, was frustration.

“It’s sad that they get treated differently because my boy is in a normal school,” Hensby says. “He has issues that other kids don’t, but we wanted him to be in that school. He’s having a really hard time now, so it’s been tough.”

Mark and Kim are keeping their best foot forward in a tireless effort to help provide Caden as normal a life as possible. That, Mark insists, is the goal.

In 94 PGA Tour starts between 2007 and 2022, Hensby collected just four top-10 finishes. After a T-7 at the Puerto Rico Open in his first of five tour starts last season, Hensby missed four cuts. The ensuing result was a tough conversation with Kim about his future – or lack thereof – in the game of golf. This past December, a then-50-year-old Hensby and his wife talked long and hard about how to best keep one another united in their effort to provide the necessary support for Caden.

“Everything was re-evaluated with my wife over Christmas,” he says. “With Caden on the spectrum, she has to deal with a lot more than most parents. That was part of the reason I was going to call it quits. I just couldn’t give them enough time.”

What they agreed on last December was to keep professional golf in the picture, but when he’s home, Hensby is to be truly home and focused on his family.

“Kim has had to deal with a lot on her own, mentally and physically,” Hensby says. “But she sees what I’m about and why I still want to pursue this. I want to make his life easier. I want to make her life easier. So that talk around Christmas was tough, but it was good.”

Genuinely poised to walk away from the very game that served him a lifeline as a frightened young kid, Hensby knew he needed to do what his father had never done for his family: be there. Before the paint of that Christmas conversation had even dried, Hensby posted four-under 215 to finish second to Ames at the Trophy Hassan II in Morocco.

“It’s going to make it easier to keep my card for sure this year,” Hensby said of his PGA Tour Champions playing prospects and scheduling ability. “Anytime you have good finishes, it also breeds confidence. You can act confident, but until you have some success, it’s pretty much just in your head. Morocco helped with the year going forward and, hopefully, created some momentum.”

By his own maths, Hensby took home more money from his second-place finish there than he had, collectively, in the previous two years. Since turning 50 last June, Hensby has made 10 starts on the PGA Tour Champions. In addition to the runner-up finish in Morocco, other top-10s with Major appeal include a third at the 2022 US Senior Open Championship and a T-8 a month earlier at the Senior PGA Championship.

“Financially, you want to be able to supply the best resources for your kid, especially my little boy,” Hensby says. “People think you just make that sort of money in a week, but there’s so much more prep and lead-up work. There’s so much more that people don’t see. So, yes, this all definitely validates what Kim and I talked about and where we want to go for the next few years… for our boy.”

A long-awaited victory was not far away. In late April, Hensby outduelled Charlie Wi in extra holes to claim the Invited Celebrity Classic in Texas – his first victory of significance since the 2005 Scandinavian Masters on the then-European Tour. He became the seventh Australian to win on the PGA Tour Champions.

Making tough choices

Hensby has found himself at a lot of crossroads in his life. While the circumstances force him to choose a direction, Hensby’s mind makes the choices. But it’s his heart that guides him down every chosen road.

“The way my dad was to me is scarring, because I know how I am to my kids,” Hensby said. “I never heard, ‘I love you.’ There just wasn’t ever anything positive, even towards the end of his life. I never got any of that. It’s really hard for a kid. There are still times – actually a few times a week – when I think about it. It never leaves you. It’s with you for life.”

Hensby admitted that before having kids of his own, he never knew for sure exactly how he would fare as a father, especially after having endured the relentless pain and sadness brought on by his own father.

“It didn’t take long for my kids to realise I was going to be a great dad,” Hensby said, fighting back tears. “I never wanted to be like my dad. I made a 360-degree turn straight away. I hug Caden and tell him I love him every day.”

Even though Hensby had long since distanced himself from his father leading up to his death in 1999, he recalls confronting his dad with one final question: “Why did you treat us the way you did?”

“It was all I knew how to do,” was his father’s only response.

“At that, I said, ‘Well, all I know is not to treat my kids the way you treated us,’” Hensby replied. “In that way, he made me a better dad – for sure.”

For all the pain and suffering Hensby was subjected to in his own family home as a little boy, rather than follow in his father’s footprints, Hensby emerged from the ashes of his past and continues to rise above. He did so by way of the directions in which he has chosen to travel.

“I think what I’m most proud of now is what I am for my kids,” he says. “I know my kids will always be able to look at me and say with confidence, ‘He was a great dad.’”

Once again, Hensby chose a higher road. And, for that, he’s in a better place. More importantly to him, though, is that everyone in his life is, too.

“I’d like to be remembered as someone who was a hard worker,” Hensby says.

“I think a lot of people misunderstand me as a person, but they don’t see a lot of the things I’ve dealt with in my life. But, more than anything, I’d most like for my kids to know their dad loves them, that he would do anything for them and that he will be there for them forever

and ever.”