What we were working on the week they won. These tips will help you, too.

[Photographs by J.D. Cuban]

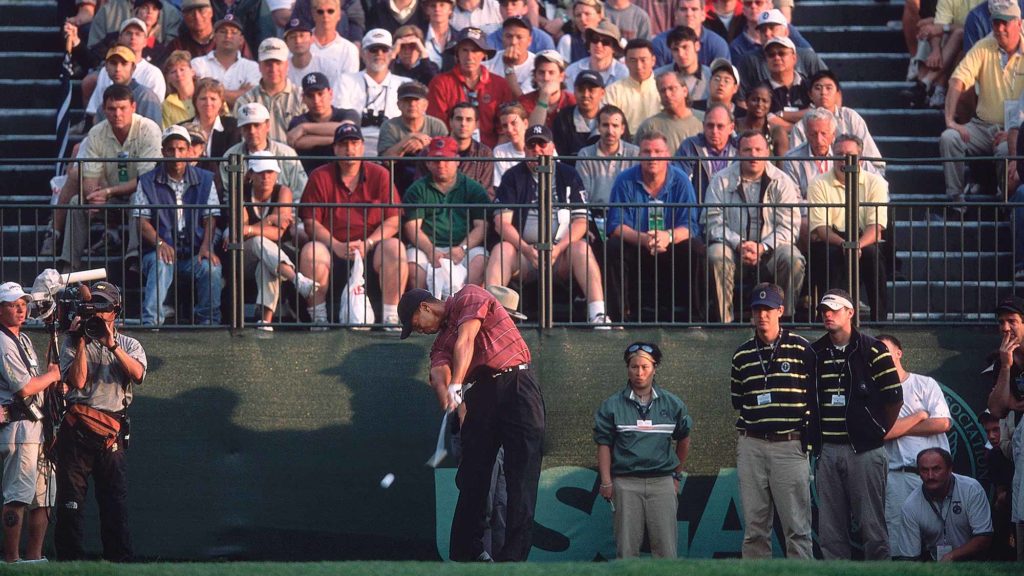

Working with Tiger Woods at the 2000 US Open at Pebble Beach wasn’t exactly a hard day at the office. I don’t think he made a swing all week that gave me pause. How many ways can you say, “Looks great. Love it.” We knew it was coming. The week before, Tiger played at Rio Secco in Las Vegas, where I have my school, and shot 64 with the wind blowing 30 miles and hour to set the course record. That win at Pebble, by 15 shots, was a snapshot of a player in complete control.

Of course, that’s Fantasyland. Even top players, Tiger included, sometimes need tweaks to get back on track. That can come in practice sessions leading up to an event or (dare I say) between rounds. When one of my players is struggling during a competitive stretch, I try to lead him back to where he’s had success. I look at it as maintenance, regaining a feel. It isn’t teaching. It’s coaching.

I always stress preparation for the Majors. Getting their swings and ball-striking in shape is a given. I’m talking about practising shots they’ll need on that course, or adjusting their set make-up. If we’re grinding over swing mechanics on site at a Major, that’s not going to end well. Same goes for you: when the stakes are high, trust what has worked.

I’ve learned that my key role with players is to be sure of what I’m asking them to do and to convince them that it’s right. I try to be straightforward and always positive. My job is to get them believing they can win. I’m going to tell you about some times when they did and what we worked on in the weeks, days or hours before it was time to play. – with Peter Morrice

Tiger Woods: Matching it up at impact

When a player is leading the US Open after each of the first three rounds, like Tiger was at Bethpage Black in 2002, you can usually assume he wants to just keep things rolling. Not Tiger. He never had much patience for hitting shots he didn’t like, and when he walked off the course on Saturday, he promptly skipped his media interviews and said to me, “We’ve got to fix something. I don’t care if we’re out here in the dark.”

The problem was his driving. He was getting the club stuck behind his body on the downswing and had to use his hands to catch it up by impact. If he was a little late, he’d block the ball to the right; a little early, and he’d hook it. The culprit was his hips. He could flash them through so fast that the club would sometimes fall behind. He needed to slow down his hip turn. The good news was, this was something we’d worked on before.

Keeping his right heel down longer into impact kept his hips in check, giving him time to get the club back in front of him, like I’m demonstrating [above]. We started with slow-motion swings, not letting that heel come up until the club went through the ball. Then he slowly added speed until he could do it full-bore.

Tiger felt better with the driver on Sunday and beat runner-up Phil Mickelson by three strokes. Swing tinkering before a final round can be tricky, but this was the greatest player of his time, maybe all-time, and he wasn’t going to have it any other way.

Your tip: Swing one-handed for a better path

I don’t see many average golfers whose hips are turning too fast, like Tiger’s were. Most amateurs are too aggressive with the upper body as they start down. When the back shoulder lurches towards the ball too soon, it pushes the club with it, setting up an out-to-in swing path through impact. If you fight a slice, this is most likely something you do.

To calm down your shoulders, try making some right-hand-only practice swings with your left hand placed on your right shoulder [above]. When you change direction at the top, apply a little pressure on the shoulder to keep it from shifting outward.

When you try this drill, remember to swing slowly at first, like Tiger did, to get a feel for it. Then pick up speed once your shoulder is under control. You’ll learn to keep the club to the inside and hit straighter drives, maybe even draw it.

Phil Mickelson: Playing under the wind

For most of his career, Phil was exclusively a high-ball hitter. His long, flowing swing, with a lot of release through impact, naturally gets the ball up. But a year or two before he won the Open Championship at Muirfield in 2013, he started experimenting with flighting the ball down with short irons and wedges. He did it by holding off his release in an abbreviated follow-through, with his arms finishing out in front of him.

I always told Phil I thought he could win an Open Championship. For a player with so much touch and creativity, he was underperforming on links courses because of his high ball flight in the wind. By early 2013, he was comfortable flighting down his short approaches. We needed to put that same action into his swings with longer clubs.

Our practice sessions focused on getting more on top of the ball on the downswing – I call it “covering the ball”. Also, bowing his lead wrist through impact [above]. Phil’s feel for this was turning down his lead hand – the right hand for a lefty – with the logo on his glove pointing towards the target.

Phil won the Scottish Open the week before Muirfield, then birdied four of the last six holes at The Open to surge ahead and win by three.

Greg Norman: Swinging on the arc

Greg was the best driver I’ve ever seen with a wooden club. He could hit it 300 yards in the air and place it wherever he wanted in the fairway. But he did have one recurring swing fault: he’d release the club out too much, instead of letting it arc around his body in the follow-through. That could produce an untimely hook.

Early in the week of the 1993 Open Championship at Royal St George’s, I could see Greg’s release was getting too outward. He needed to finish more around to the left. The best way to feel a more rounded follow-through is to hit balls on a sideslope with the ball above your feet [below]. One afternoon, we looked around and found a sidehill lie near the equipment vans. After a few minutes, the crowds found us, and one of the tournament officials tried to move us, saying he could not provide security off the practice area. Greg said, “I have my own security – Butch and Tony (Tony Navarro was his caddie). I need to stay right here and practise for a while.”

In a short time, Greg had a good feel for releasing more around his body. His driving was phenomenal that week, and his 64 on Sunday to win is still the best round of golf I’ve ever witnessed.

Your tip: Grip it split-handed to cure a slice

Practising on a sideslope is great for slicers, who typically swing too up and down and need more of a baseball-swing feel.

Like Greg, you might struggle to find a practice spot, so here’s a substitute drill you can do anywhere. Grip the club with a small gap between your hands and make swings. You’ll instantly feel your left elbow fold in the follow-through and your right forearm rotate over it [above]. That will help you square the face and lose the slice.

Dustin Johnson: Falling in love with the fade

Dustin is clearly an elite athlete: 6-foot-4, super flexible with speed to burn. But what makes him a tremendous player is as much his attitude as any physical gifts. I’m talking about how he chooses to motivate himself – and when.

Remember the final green of the 2015 US Open at Chambers Bay? Dustin was on in two on the par 5, but then three-putted from 12 feet when a two-putt would have forced a playoff with Jordan Spieth. A lot of people asked me if DJ would be OK, would he get over it? The truth is, he was fine. He dismissed it quickly. To him, it was a fluke, and he let it go, choosing not to make it a motivator.

When Dustin was leading down the stretch at the US Open the next year at Oakmont, people were wondering if he could close out a Major. Let me promise you, he was focused on the task in front of him, not about what had happened the year before. In fact, it was driving, not putting, that decided the winner that week.

In the months before Oakmont, I was working with DJ on playing a fade off the tee. Our process was simple: aim the clubface where you want the ball to end up, then align your body to the left and swing where your body is aimed [above]. The ball would start left and slide back to the target. He’d hit it great in practice but would go back to his draw in competition.

Then, one day he called me after a casual round back home in Florida. He said he hit a fade off every tee that day and played great. He went on to say something like, “You know, I think that’s the shot for me. I’m going to go with it,” as if he just discovered a new idea. I laughed. That day he got his motivation.

Dustin won the 2016 US Open by three strokes, leading the field in driving distance at 317 yards, nearly 10 yards longer than the next player, Justin Thomas. He can still move the ball any way he wants, but clearly the fade has become his go-to shot. (He also won the 2020 Masters hitting mostly fades.) When Dustin drives it well, he is the best player in the world.

Your tip: Use your setup to draw it, too

I taught Dustin to fade the ball the way Jack Nicklaus used to do it. I call it a “release fade”, because you’re not trying to hold the clubface open to make the ball fade – that move often leads to a slice. Instead, you set the face open at address, relative to where your body is aimed, and then make your normal swing. It’s like hitting a straight shot. The only difference is that your body is aimed more to the left of the target.

To hit a draw, which I know most of you would love to do, just reverse the positions. You still aim the clubface where you want the ball to finish, but now you align your body to the right [above]. Then, when you swing along your body lines, the ball starts to the right and curves to the left. Whichever shot you choose to play, remember that you don’t have to try to manipulate the face at impact. In effect, the setup creates the shot shape you want.

Gary Woodland: Adding more turn

A couple of weeks before the 2019 US Open at Pebble Beach, Gary came to see me because he was hitting a “double cross” with his driver. He plays a fade, so he was setting up open, but his shots were starting left and then hooking. The issue was his backswing. He wasn’t getting enough turn, so he was forcing the downswing with his hands and arms, which closed the clubface. Swinging left with a shut face is not a move you want to take to the US Open.

After a few swings, I could see Gary was locked up in his hips. He needed to turn his right hip out of the way going back, so I gave him a tip I learned from Greg Norman: right pocket back. Greg used to call it “RPB”. The feeling is to turn your front-right pocket behind you [above]. When Gary tried it, his lower-body turn instantly increased, which allowed him to stretch his overall turn. He didn’t feel the need to rush down, so the clubface started coming in a little open. His fade was back.

I saw Gary early in the week at Pebble and asked him how he was doing. He said the driver was working great, and he didn’t need me. That little tweak changed his ball flight by 30 or 40 yards. He looked confident on the tee all four rounds and won by three over Brooks Koepka.

Stewart Cink: Shallowing out

Stewart has one of the longest, widest swing arcs on the PGA Tour. He does a great job extending his arms on the backswing and making a full turn to the top, which equates to big distance. (Last year, at age 48, he averaged 307 yards off the tee to rank in the top 30 on tour.)

In the days preceding the 2009 Open Championship at Turnberry, Stewart was not turning his shoulders like normal. He was extending his arms, but because his turn was reduced, the backswing was too upright – and he was getting narrow on the downswing. As a result, he had to back up coming into the ball to shallow out his swing.

On the practice tee at Turnberry, we worked on getting him to turn his left shoulder behind the ball [above]. Stewart could easily do it; he just needed some reps. We did a lot of slow-motion swings to ingrain the shallower downswing. (With less flexible players, I have them think about turning the chest over the right knee to load behind the ball.)

Stewart famously outlasted Tom Watson that week. Tom had a chance to win a Major championship at 59 years old, which would have been an unimaginable feat, but Stewart beat him in a four-hole aggregate playoff to take home the claret jug.

Jimmy Walker: Extending through impact

Jimmy has always had an old-school swing with a lot of knee drive into the ball, which causes him to tilt away from the target through impact and make a more handsy release than you see in most top players today. It’s a powerful move, but he can get into trouble with too much backward tilt, requiring precise timing with his hands to square the clubface. In our practice sessions before the 2016 PGA Championship at Baltusrol, we saw that he needed to reduce the spine tilt and get his body more centred through the strike.

A good feel for Jimmy was to really extend his right arm out to the target through impact [above]. Doing that literally pulled him off his right side, preventing him from leaning back too much. The image was as if he were going to shake hands with the target, stretching out his right hand as the club swung through. Jimmy had to feel like his right arm and shoulder were staying higher through impact, not dropping down with his upper body backing up.

He got the gist of it very quickly and hit the ball beautifully at Baltusrol to claim a one-shot victory over Jason Day, who was the world No.1 at the time. Go, Jimmy!

Your tip: Work on your finish to stripe it

Extending through impact worked for Jimmy, but feeling anything when the club is speeding at 100-plus miles an hour can be a challenging task.

That said, getting the right side through is a great thought for any golfer, so here’s another take on it: swing to a finish where your right shoulder is closer to the target than anything else [above]. Sometimes trying to reach a destination can help you clean up your positions along the way.