For many golfers, a constructive way of thinking about your limitations comes from a baseball movie.

The scene is from “Major League,” the 1989 comedy about an eclectic collection of baseball players who tended to have at least one deficiency that impeded their careers. One is Pedro Cerrano, a bald, enigmatic power hitter who walks into his first batting practice session during spring training and proceeds to hammer a series of fastballs far over the fence.

Observers behind the batting cage are astonished. What a find! Then the batting practice pitcher throws a curveball, and Cerrano swings and misses like he’s never hit a baseball before.

Most golfers who are intent on whittling their handicaps down feel like Cerrano. We intersperse displays of skill, even excellence, with moments of flailing incompetence. We believe if we could just figure out this one thing, we’d be set.

It is rarely that simple, of course. But when it comes to understanding what’s stalling your progress, a decent starting point is identifying your version of Cerrano’s curveball.

If you’ve followed our season-long project in which a collection of Golf Digest editors have shared their handicap progress, you know it includes room for assessing specific parts of our games. This month, it looks like this:

Those assessments, whether it’s Luke’s A grade for putting or Greg’s B- ball-striking, are all subjective. They are grades relative to where we were and where we believe we should be. But perhaps a better way of looking at it is by understanding the tendencies of other players, which you can do through our “How Do You Compare?” interactive.

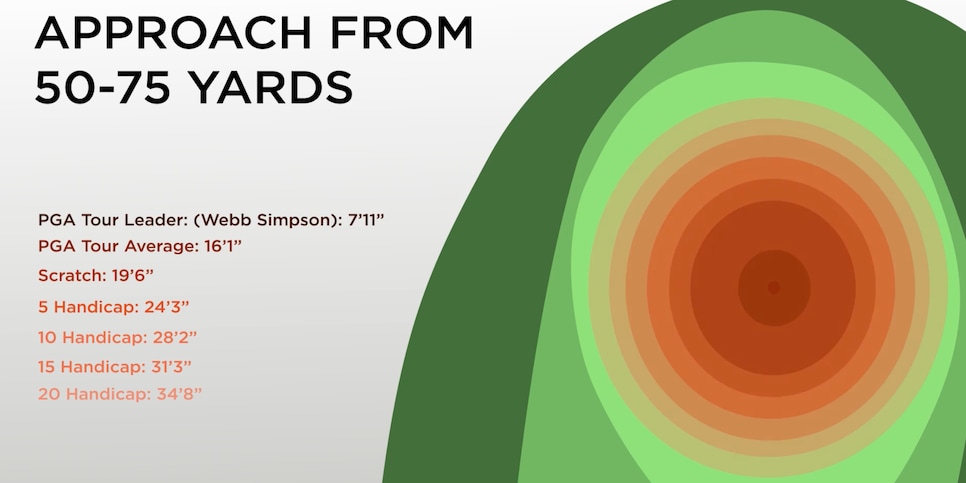

Using average golfer stats through Arccos, which has tracked millions of rounds against a broad spectrum of ability levels, you can see how you stack up against players of your handicap. But a more useful way of looking at it might be to examine the stats of players one level better and see if it crystallizes a new area of focus.

Greg, for example, noted he’s seen tangible improvements in his driving and his putting. But from a wedge distance of inside 100 yards, he’s still costing himself strokes.

“There’s little consistency there nor any rhyme or reason for when I connect and when I botch it,” he said. “It’s not that I can’t get it on the green. It’s just that when I don’t … I really don’t.”

According to How Do You Compare?, a 20-handicap averages a 34’8” proximity to their hole on approach shots from 50-75 yards. That sounds like it’d be a decent goal for Greg, and not an insignificant one. When course-management experts like Scott Fawcett outline their essential pillars for scoring, they often cite the importance of making sure your next shot after a wedge is a putt. In other words, you need to get these short-range shots on the green.

The only other option is to avoid that distance altogether. But that’s as realistic as a major league hitter never facing a curveball.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com