Months of hard work led to my first major. Here’s what you can learn.

Photographs by Jensen Larson

Editor’s note: Some Major champions seem destined for greatness; their triumphs are not a stunning development, rather an eventuality. Matt Fitzpatrick isn’t one of those guys – his words, not ours.

Winning the US Amateur at 18 and making a Ryder Cup team before 22 might make you think Fitzpatrick would be satisfied with his place among the game’s best. But before 2022 began, Fitz and his coach, Mike Walker, knew that despite those accomplishments – and a top-50 world ranking – his game didn’t stack up with the very best golfers.

“He played with Brooks Koepka and Justin Thomas at the 2020 Masters,” Walker says. “Matt hit a 7-wood into 11, while those boys flicked short irons. Matt didn’t have a chance. We needed to make some serious strides if he was to ever reach that level.”

Fitzpatrick’s analytical nature has fuelled his quest to get all he can out of his 5-foot-9 frame. “Some people are born with speed I had to build mine,” he says. With that in mind, Fitzpatrick consults a swing coach, a putting coach, a statistician, a trainer, a biomechanist and a performance coach. He logs every competitive shot and pores over spreadsheets like a financial analyst. “He’ll turn over every last stone to find that 1 percent,” Walker says. “And then he’ll go out and find another stone.”

The hard work paid off at The Country Club last June, when he won the US Open and joined Jack Nicklaus as the only men to win a US Amateur and the US Open on the same course. On these pages, Fitzpatrick shares some key lessons from his journey to become a Major champion. – Dan Rapaport

For power, get more out of your backswing

Earlier in my career, there were many weeks I’d show up to the golf course knowing I couldn’t contend because of my distance shortcomings. I wanted to get longer, of course, but I didn’t want to fundamentally change my swing and sacrifice accuracy. My coach and I decided to consult biomechanist Sasho MacKenzie, who helped us craft a plan to add speed gradually. I also worked with my trainer, Matt Roberts, to make sure my body could support the changes. It’s worked wonders – I’ve added about 8 miles per hour of clubhead speed during the past three years, and I’m averaging 15 yards more off the tee (303.8-yard average in 2022). I’m hitting it past guys who used to hit it past me. It’s a nice feeling.

Part of my speed comes from my fast takeaway – yes, the takeaway. You might have been told to take the club back slow, but as long as you’re in sequence, ripping the club back faster just gives you a head start on building power. Don’t be afraid to add a little speed to your backswing. My takeaway for my stock driver shot is much faster than what you usually see on tour.

If I really want to crank one – say it’s a wide-open par 5 or I really need to carry a bunker – I’ll use a trick

Dr MacKenzie taught me and lift my left heel high off the ground in the backswing [above right]. It allows me to make a bigger turn, loading up on my back foot, before I start down and explode through the ball.

Flatten your lead wrist for cleaner contact

At the end of 2021, we broke down my statistics and found one glaring weakness – my approach play. Look at the top players in strokes gained/approach the green on the PGA Tour, and it’s all the guys at the top of the world ranking. If I was going to compete with them, my iron play had to improve.

If you look at these two photos, you’ll notice my backswing has changed. (The new one is on the far right.) One of the big problems with my irons was bottom control. The low point was inconsistent, and I wasn’t clipping the ball off the turf cleanly enough.

Mike and I decided to take some wrist set out of my backswing for better consistency. My left wrist used to be a little extended or cupped [above left] at the top of the backswing, and we wanted to get it in a much more neutral (flat) position [above right]. When I started taking the club to the top with a flatter left wrist, I felt like I had Bryson DeChambeau’s swing – my arms felt straight and rigid. Now it feels normal, and my contact with irons has been much better.

Try keeping your lead wrist flat when you swing back. If you cup it, you’ll have to let it flatten in the downswing. That move might hurt your consistency.

Try left-hand low for a tidier short game

I first started chipping “cack-handed” (as we call it back in England) as a drill. It worked so well, I put it in play. Holding the club with my left hand lower than the right [above left] helped eliminate my tendency in chipping to drag the handle towards the target through impact, which leads to inconsistent contact. If you drag the handle cack-handed, you will shank, skull or fat it every time.

Another thing I like about using this grip is that you usually know what the ball is going to do. When I held the club the normal way, I’d sometimes get a ball that rode up the clubface and spun a lot or one that would tumble forward with virtually no spin. The variance was frustrating, and it cost me shots. Keeping track of my performance during practice while chipping normally and chipping cack-handed, the results were pretty obvious which way to go.

I realise it might take some convincing – and courage – for you to switch to this unusual grip, but I think you’ll be amazed how effective it is for improving contact. I actually like it so much that I’m working on

extending how far out from the hole I can use this grip. I’d like to eventually be able to hit cack-handed shots from as far out as 75 yards.

For great distance control, put a steady stroke on it

I’ve always been a good putter, especially starting the ball on the correct line. But putting is a lot more than that. Perhaps most crucially, you’ve got to control speed. Sometimes my stroke is fast going back, slows in transition, and then speeds up again through the ball. But you don’t want to accelerate through the ball. You want your speed to be steady. My putting coach, Phil Kenyon, and I have worked on a drill for rhythm that promotes consistent contact. That’s a prerequisite for speed control. I put a penny on the back of my putter [above left] and make a stroke. If the penny falls to the ground as I start my through-stroke [above centre], my speed will be steady into the ball.

Challenge yourself for meaningful practice

I’m not a guy who practises only on the course, but I’m also not a fan of mindless ball-beating on the range. I have worked with performance coach Steven Robinson for a few years to help me get the most out of my practice and identify areas for improvement. Steve does a great job of keeping things fun and gamified – I’d get bored otherwise.

Here’s one of my favourite games. Start by hitting a shot that carries as close to 70 yards as possible, but no less than that. Then hit one as close to 100 yards as possible, without going longer than that. You then repeat the process. Say your first shot went 74 yards and your second 96 yards, that means the landing area is now even tighter – 74 and 96. The goal is to hit as many shots as possible until meeting in the middle.

Whether it’s this drill or another one – say, alternating chipping short of a flag and past it – try to simulate real-round pressure. You’ll feel more comfortable when it’s time for the real thing.

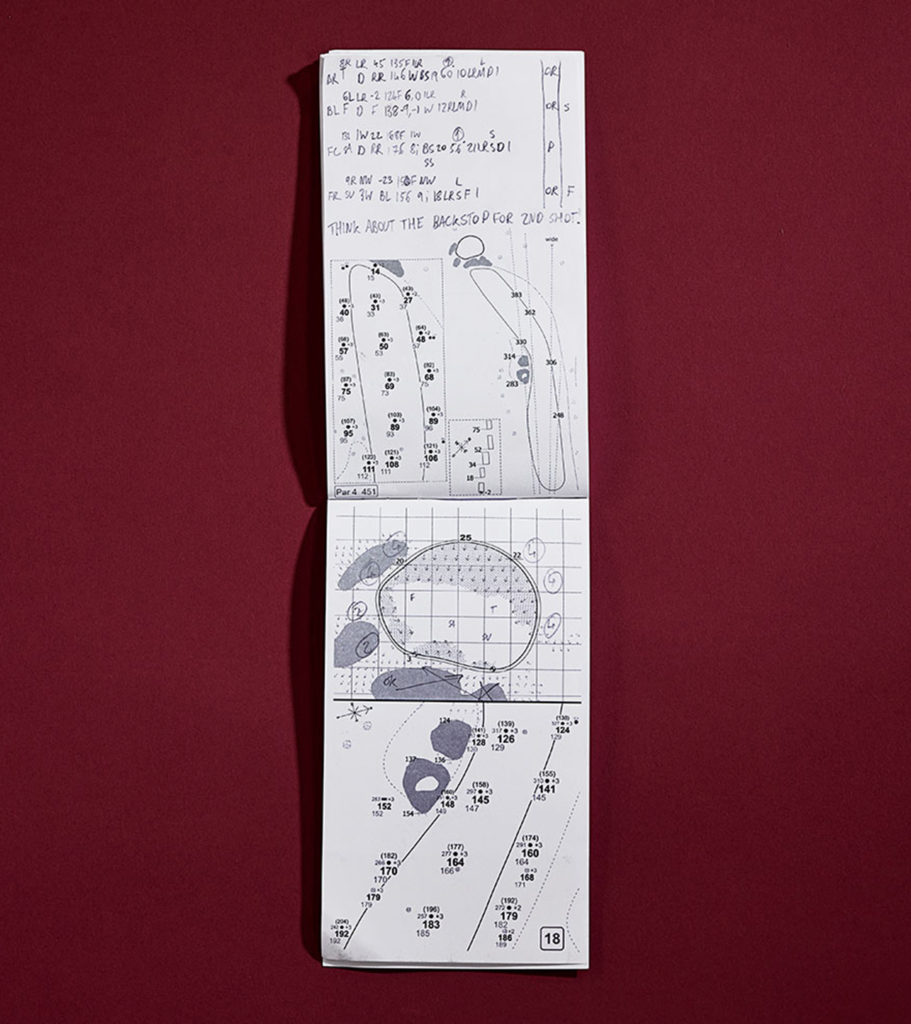

My yardage book: Granted, it’s a bit much. But all these symbols matter to me

I fancy myself a fast player, and I’ve publicly bemoaned slow play more than a few times, so I devised a code for my yardage books to quickly note the relevant info. I don’t want to slow down my group while deciding what to hit.

I record the outcome of every shot in these books and have the results entered into a stat program developed by tour pro Edoardo Molinari. I know that sounds a little over the top, but logging all those numbers and then reviewing them reveals an honest assessment of your game. For an average golfer like you, saying you hit your 7-iron 150 yards might be the default answer. But do you really? Or learning you miss to the right way more often than to the left might influence your aim. Stats don’t lie.

Back to the coding in my yardage books, this is the 18th hole from last year’s US Open. There are different entries for each of the rounds. On Sunday, I pulled my 3-wood into that left bunker and then hit the shot of my life to save par and cap off the best round of my career – a two-under 68 to win the US Open.

From Friday (124F, 6, 0, 138, -9, -1)

For this shot, it was 124 yards to the front of the green (124F) and 138 to the flat. The 6 means I was aiming to hit my approach six yards right of the flag, and the 0 means I was trying to hit it pin-high. The -9 means I hit it nine yards left of my target, and the -1 is one yard short. I’ll only keep this level of stats from the fairway – there’s too much variability from any other lie that’s out of my control.

From Sunday (FR, SU, 9R)

The FR means the pin was in the front right. SU is an abbreviation for Sunday. And 9R means the pin was nine paces off the right side of the green.

From Sunday (NW, 3W, -23, BL)

NW means there was no wind, as opposed to LR for left-to-right wind or DW for downwind. I hit 3-wood off the tee (3W)and missed it 23 yards left of my target (-23), and it finished in the bunker left (BL).

From Sunday (150F, 156, NW, 9i)

This was the bunker shot on 18. I had 150 yards to the front of the green, 156 to the flag, there was no wind, and I hit 9-iron. What you don’t see here is, if my ball finished one yard farther right in the bunker, I probably would have had to pitch out.

From Sunday (18 LR, S, F, 1)

I hit the shot to 18 feet, and the putt was left to right. I judge breaks by small, medium or large, and this one was small (S). The putt was flat (F) instead of downhill or uphill. The 1 means I missed it by a foot.

ALL rounds (OR, P, F, S)

I use this area for general info. The left column notes missed putts. OR means I overread it. On Saturday, my pace (P) was off. The right column is for greens in reg. I’ll write an F if I missed on the fat side of the green, and S if I’m on the short side of the hole.