We look back at one of the most significant moments in golf – the 1960 British Open.

Today, Kel Nagle is regarded as the third Australian golfer to win a Major.

But at the height of their careers, Jim Ferrier, Peter Thomson and Nagle were not considered ‘Major winners’. For the idea of a ‘Major’ championship was not yet born.

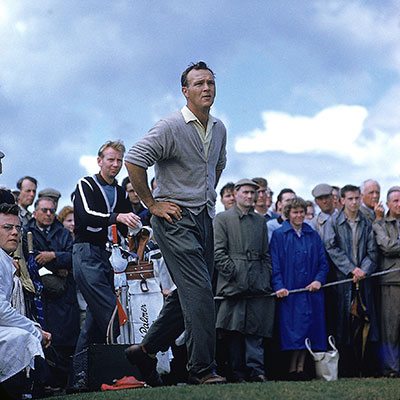

When Ferrier won the US PGA Championship in 1947, when Thomson claimed the British Open four times between 1954 and 1958 and when Nagle sank his final putt at the Centenary Open at St Andrews in 1960 – to beat Arnold Palmer, (then the undisputed champion of the golf world) the term wasn’t in golf’s lexicon. Not yet, anyway.

There was, however, a ‘Grand Slam’ of golf – the four events won by Bobby Jones in 1930. When Jones won the US Open and Amateur, as well as the British Open and Amateur, it was a phenomenal achievement. Professional golf had nothing to match it. Through the 1950s, it wasn’t even possible to get international agreement as to what were the four biggest pro tournaments in the world.

Palmer changed that when he made plans to enter the 1960 British Open. In April, he won his second Masters. During the US Open, he announced in an article in the Saturday Evening Post that he was going for a ‘slam’: The Masters, US and British Opens, and the US PGA Championship.

“The odds against it must be at least 1000-1,” Palmer wrote. “Yet I feel confident that, with a little luck, it can be done. I want to be the one to do it.”

Palmer promptly went out and shot a final-round 65 to win the US Open. Legend has it that Palmer and his long-time friend and ghost writer, Bob Drum of the Pittsburgh Press, invented the concept of the ‘Grand Slam’ of professional golf on the flight from the US to Ireland, where Palmer was going to play in the Canada Cup (now the World Cup) before heading to Scotland.

In fact, the press – inspired by that Evening Post story – had jumped on the idea even before they were on the plane. As one wire story written after the US Open reported, “Arnold Palmer is en route to Europe today in search of the greatest grand slam in golfing history.” Another suggested Palmer was chasing “the first Grand Slam in pro history.”

This was a concept whose time had come. From Palmer to Jordan Spieth, whenever a highly ranked golfer dominates the Masters, the question is asked: “Can he win the Slam?” Only problem is, it’s incredibly hard to achieve. Only Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods have completed this Slam over their careers.

Palmer and Drum also liked to describe the four tournaments that made up their slam as “Majors” and that caught on as well. When the World Series of Golf was introduced in the US in 1962, featuring just the winners of the Masters, US Open, British Open and the PGA, it was officially promoted as “a 36-hole television package designed to match the winners of the four Major golf championships.”

Palmer used the term as a reflex. In 1964, he told reporters: “I’m going to concentrate on winning the Major championships … I still want to win the four Major titles in one year and I hope I don’t lose that ambition for a while.”

Soon, everyone was talking that way. Today, every winner of these four big tournaments, starting with Willie Park Sr at the inaugural British Open in 1860 and including Kel Nagle 100 years later, is considered a Major champion.

PALMER PAVES THE WAY

Palmer’s influence goes further. Many scribes divide British Open history into two eras: pre and post-Palmer.

American interest in the Open declined after World War II. The tournament was diminished as a result. In 1958, when Thomson beat Dave Thomas in a playoff, there were no high-calibre Americans in the field. A year later, there were no Americans at all.

Trans-Atlantic travel was expensive and a grind. The prizemoney was less than that on offer at most US tournaments. As well, the Open had stringent qualifying rules – everyone had to survive a 36-hole qualifier just to make the final field.

Palmer, a genuine golf traditionalist, saw beyond this. Walter Hagen had told him: “Arnie, you ain’t nothin’ ’til you win the British Open.” Palmer duly entered the 1960 Open and quickly captured the hearts of UK fans. His presence doubled gate receipts. Other American golfers followed him. Jack Nicklaus made his Open debut in 1962; his first victory (of three) came four years later. Phil Rodgers lost a playoff to New Zealand’s Bob Charles in 1963. Tony Lema won in 1964. By the time Nicklaus beat countryman Doug Sanders in a playoff in 1970, the Open’s prestige was not just restored, it was enhanced.

In the US papers of July 1960, Palmer’s British Open challenge was the biggest story in golf, more important than Art Wall’s win in the richer Canadian Open that took place at the same time. The respected US golf writer Curt Sampson describes the 1960 Open as “the most important Open of the modern era.” His fellow golf historian, David Hamilton called it “the beginning of a golden era for the Open.”

“The only thing I regret about it,” Palmer told the Independent in 2011, “is that Kel Nagle beat me.”

FROM THE PRO SHOP TO THE PRO TOUR

Nagle was unheralded outside Australia when he arrived at St Andrews. He was 39 and competing in just his fourth Major. Back in 1936, he had landed a job as a trainee professional at Pymble Golf Club in Sydney, but six years of war meant he didn’t appear in an Australian Open until 1946, when he finished nine shots behind Ozzie Pickworth.

He won the Australian PGA Championship in 1949, the NSW Open in 1950 and three straight WA Opens (1950-1952. But Nagle

didn’t announce himself as a true top-liner until 1953, when he dominated the $15,000 McWilliams Wines tournament at The Australian Golf Club, winning by seven shots from Argentina’s Robert De Vicenzo.

“Yes, I would,” said the new champion, when asked if he’d like to play in America. “But the expenses are far too high.”

Nagle kept himself mostly in Australia and New Zealand. He had tried his luck overseas in 1951, when he tied for 19th at the British Open. A year on from his McWilliams victory, he and Thomson won the Canada Cup (now the World Cup) in Montreal. Twelve months later, using the round-the-world ticket Cup organisers had given him so he and Thomson could defend their title, Nagle ventured to St Andrews for a second unsuccessful shot at the Open.

It wasn’t until 1960 that he headed overseas again. A second Canada Cup win (again with Thomson, this time at Royal Melbourne), meant he could jet to the Masters, where he missed the cut, and to the rich Colonial Invitational in Texas, where he lost by a shot to Julius Boros. The bookies offered long odds about Nagle winning the Open, but they weren’t to know he was playing with new set of Spalding irons he’d picked up in America. He was contracted to PGF but on Thomson’s urging sought and gained permission to make the swap. Nagle had also purchased a new driver at the Colonial. Years later, renowned golf writer Phil Tresidder recalled Nagle reminiscing, “If you had told me to hit to the left or to the right, or down the middle, I could have done it with that driver.”

Thomson liked his friend’s chances. He implored Nagle to keep out of the infamous St Andrews bunkers and showed him where to aim his approach shots away from the flags. “It was like signposting the course for me,” Nagle told the Sydney Morning Herald in 2010.

What only those closest to Nagle knew was that he was battling an annoying ache in his right little finger. Throughout the week of the Open he’d apply ointment to the finger, bathe it in hot and cold water to try to loosen it up, and shake hands with his left hand.

AN OPEN UPSET FOR THE AGES

In assessing the 1960 Open’s place in history, a crucial factor emerges: it was a fantastic tournament. The crowds were substantial; the golf was often magnificent; and the tension was palpable. The first round, played on a Wednesday, belonged to De Vicenzo, who fired a 67 to lead by two from Nagle and another Argentinian, Fidel de Luca. Nagle and de Luca were both out in 38, back in 31, comebacks that impressed the Glasgow Herald’s Cyril Horne.

“St Andrains were dumbfounded that anyone should treat the inward half of their great pride so scurvily,” Horne reported. “Nagle went daft on the greens on the inward half, holing putts of 10 feet at the 10th, 12 feet at the 14th, 12 yards at the 15th, four yards at the 16th, and one of 30 yards from off the green at the Road Hole [the 17th].”

Nagle had set the tone for his tournament. He was, to use Horne’s description, “uncannily accurate” from two to six metres. On day two, he and De Vicenzo both shot 67s; on the third morning, Nagle’s 71 to De Vicenzo’s 75 gave the Australian a two-shot lead. But Palmer – who’d started 70-71 – was now lurking, four shots off the lead, and would have been even closer had he not three-putted the final two holes. Reporters wondered if he’d been distracted by the storm that swept over St Andrews as he completed his round. The final 18 holes were postponed until the Saturday, something that hadn’t happened since 1910, when James Braid won the ‘Jubilee’ Open.

Golf World magazine would later suggest that with the weather improved, most observers now believed an American victory was a formality. As if to prove the point, Palmer birdied the first two holes of his final round. But his surge stalled. All three leaders went out in 34.

De Vicenzo dropped a shot at 11, Palmer gained one at 13, but the mood didn’t really change until the 15th, when Nagle, to general astonishment, three putted. At the Road Hole, Palmer risked all by going for the pin and almost played the perfect shot … the ball teetered on the back of the putting surface, which would have left him a three-metre putt for a three, but then, slowly, cruelly, it slipped down and away towards the road beyond the green.

The next 15 minutes were full of drama. Palmer grabbed for his putter and produced a remarkable, impeccably judged shot that left him just half a metre for his four. From the 17th tee, Nagle watched the American sink his putt to a huge roar. He then played the hole conventionally, as Thomson had shown him, running his approach on to the front edge of the green. He putted up to about eight feet.

Palmer was charging home. He played a wonderful wedge into the 72nd hole, leaving himself three feet for a three. That would reduce the Australian’s lead to one.

Nagle was by nature a quick player. He was tempted to rush, to putt before Palmer. Instead, he waited … and saw Palmer in the distance make the putt that equalled Bobby Locke’s record low four-round score for an Open at St Andrews. Now came Nagle’s moment. Greatness was called for…

“If ever a brave shot was played by anyone in the history of the game of golf, it was by Nagle on the 71st green,” was the verdict of Golfing magazine.

“Here indeed was a test of nerves,” wrote Cyril Horne. “But he maintained his reputation.”

“It was the best putt I ever hit,’ Nagle told the Sydney Morning Herald’s Rod Humphries in 1976. “It had a right-to-left burrow. It never looked like missing.”

Over the four days, Nagle went 3-3-4-4 on the Road Hole, sinking long or awkward putts every time. Palmer’s scores were 5-5-5-4. He three-putted on all but the final day.

Nagle, needing a four, played the final hole perfectly … almost. His drive was typically smooth to the left of the fairway and he lobbed a 9-iron to within a metre of the hole. But then he missed the putt that would have left him on 277 – an Open record. His final putt, just a few inches, was made without a flourish. De Vicenzo, England’s Bernard Hunt and South Africa’s Harold Henning were tied for third on 282.

Nagle always made a point of highlighting Peter Thomson’s role in guiding him to victory. The then four-time champion (he would win again in 1965) had one more contribution. “When he finished, he had no way of making it through the crowd to this hotel, but he needed a jacket for the presentation,” Thomson wrote in 2005. “I’d finished some time earlier so I took off my jacket and gave it to him. In the picture taken of him, holding the trophy, he is wearing my jacket.”

After the presentation, the new champion was confronted by a large group of autograph seekers, most of them children. “Just wait until I put these inside, kids,” he said, glancing down at the trophies nestled on his forearm. “Then I’ll be right out.”

Which is exactly what happened. Despite his aching finger and with two policemen controlling the queue, the new champion worked for half an hour, until the last piece of paper was signed.

A LEGACY LIVES ON

Nagle didn’t single-handedly change the course of golfing history. It was Palmer who inspired the British Open’s revival. However, by beating Palmer at St Andrews and doing so in such a dignified, nerveless manner, Nagle gave the championship a sense of quality it might not have had if the great American won comfortably.

Pat Ward-Thomas, the Guardian’s long-time golf correspondent, argued Nagle’s performance was “as fine an example of golfing character as any I have known.”

Because of what happened at the Centenary Open, there was no suggestion Palmer’s triumphs at Birkdale (1961) and Troon (1962) were soft or easy.

Nagle didn’t win another Major. He did, though, compile a superb Open record through the 1960s: second place in 1962, fourth in 1963 and 1966, fifth in 1961 and 1965, ninth in 1969. He won the French and Swiss Opens in 1961, the Canadian Open in 1964, and lost an 18-hole playoff at the 1965 US Open to Gary Player. He continued to win in Australia until 1977, when he won the WA PGA Championship four months after his 56th birthday. In total, Nagle won more than 60 times in Australasia. He was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2007.

He died in January this year, aged 94. “We had some exciting times together, especially at my first Open Championship when he won and I finished second,” Palmer remembered.

As the Open returns to St Andrews this month, when we hear the terms ‘Major’ and ‘Grand Slam’, we should think of Palmer, Nagle and their thrilling encounter 55 years ago. And of what it meant to the history of the game they played so well.