One night, in 1922, Chester Hogan, a rural Texas blacksmith, was arguing with his wife. Then he went into another room, pulled a .38 revolver from his bag, and shot himself. According to some accounts, his 9-year-old son, Ben, was in the room with him.

What did Ben Hogan witness – did he see the suicide? What was the impact of the trauma? Of growing up without a father? Of knowing that the man who made him, whom he idolised, came to the irrevocable decision that life was not worth living?

Child victims of a parent’s suicide often are susceptible to depression, social maladjustment and post-traumatic stress disorder. More pressing for the Hogans was the fact that they were plunged into poverty. Young Ben went to work. To help the family make ends meet, he sold newspapers. Then one day, at age 11, he hiked seven miles to Glen Garden Country Club after he’d heard you could make money carrying golfers’ bags.

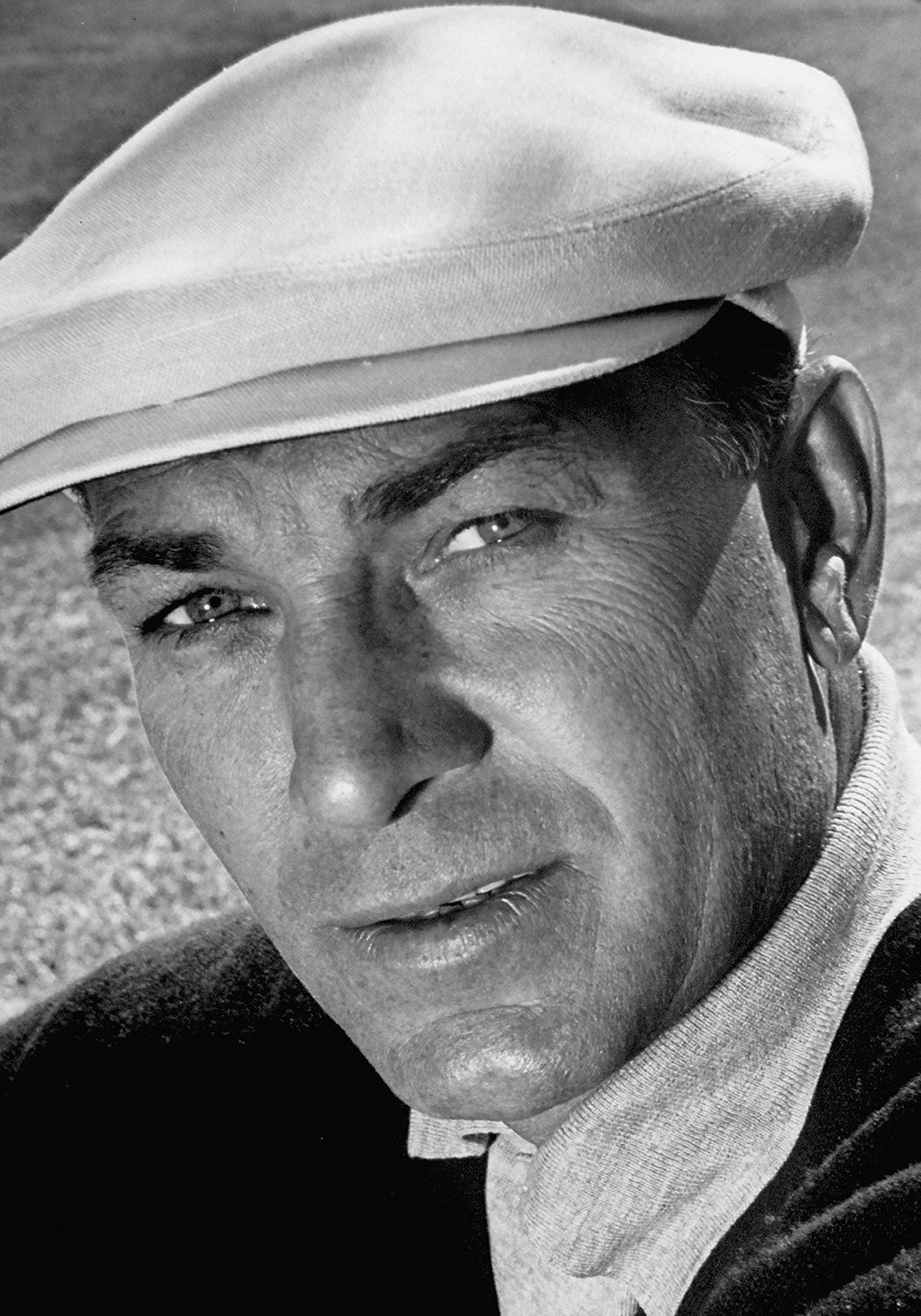

Golf adopted Hogan. His clubs became his hammer, the practice tee his anvil. He forged something beautiful. Ben Hogan became Hogan.

Hogan’s story has a mythic quality. Not as naturally gifted as Sam Snead or Byron Nelson, Hogan rose to the top of the game through grit and sheer bloody-mindedness. For years, he fought a round-wrecking hook that he described as being like “a rattlesnake in your pocket”. He didn’t win a tournament until he was 27. With his career interrupted by World War II – Hogan served in the Army Air Forces – he didn’t win his first Major championship until he was 34. Three years later, a head-on collision with a Greyhound bus nearly killed him. With his legs shattered, doctors wondered if he’d ever walk again; the next year, Hogan won the US Open.

In 1953, Hogan won the Masters by five strokes and the US Open by six. Then he made his only appearance in the British Open, at Carnoustie, where he silently dissected one of the game’s most brutal, unforgiving links, improving his score each day to win by four strokes. It was both the pinnacle and exclamation mark of an extraordinary career. Wracked with pain, Hogan entered just six tournaments that year. He won five of them. He returned from Carnoustie to

a ticker-tape parade on Broadway. After that he retreated to Texas and largely stayed there. The limelight always had made him squint.

For many, Hogan is an icon of what it means to be a golfer and a man. Clean-shaven, immaculately dressed, scrupulously honest. Modest. Hard-working. Disciplined. Stoical. A lone wolf, battling nature and the elements, internal ones as well as external.

Golf prides itself on its life lessons. The game comes with a set of rules, a tribe and village elders. From role models like Hogan, boys can learn to be men (something many aren’t learning at home: one in three American kids, like the teenage Hogan, don’t live with their dad). They learn that the game is hard, and rewards are few. Good bounces can come disguised as bad bounces, and vice versa. Play the ball as it lies. No one saw you inadvertently break a rule? Call a penalty on yourself. Take dead aim. Don’t complain; don’t explain. Got a problem? Fix it. “Dig it out of the dirt.”

Yet Hogan was famously taciturn and cold. He eschewed small talk or, more accurately, talk. He hated giving interviews. He could stop a young autograph hunter in his tracks with an icy stare. As a kid, Hogan hovered like a disapproving eminence grise over my fledgling attempts to become a grown-up. He seemed like every hard-ass teacher I’d ever had at school, every disapproving ex-military British golf-club secretary who ever upbraided me and my friends for some absurdly petty transgression, every unnamed Victorian ancestor who peered unsmilingly out from old photograph albums. I read in one of Jack Nicklaus’ autobiographies that he liked Hogan because he wasn’t effusive, and in Nicklaus’ view, effusiveness was bad. My ensuing monosyllabic attempt

to be uneffusive was short-lived.

Childless by choice, Hogan supposedly built a house with only one bedroom to foreclose any possibility of overnight visitors. (Even if this story is apocryphal, it’s revealing that it’s so often told.) He famously failed to notice when his playing partner Claude Harmon aced the 12th hole at the Masters one year. As they walked off the green, Hogan said, “You know, that’s the first time I ever birdied that hole, Claude.” Was he dissociated – or just rude?

In a 2015 interview, Arnold Palmer recalled Hogan’s lifelong frostiness, never once addressing Palmer by name. “It did bother me,” he said. “And I wasn’t ever quite sure why he didn’t. But ’til the day he passed, I never remember him calling my name.”

“Ben was a great mystery to a lot of people, maybe even to himself,” Byron Nelson told Hogan biographer James Dodson. “For some reason, I don’t know why, he wanted it that way. He wouldn’t let people in.”

The Austrian psychoanalyst Alfred Adler argued that men often overcompensate for their fear of vulnerability with a lurch towards stereotypical male aggression and competition. What fellow analyst Carl Jung called the anima, the feminine, is denied; the animus is embraced. (To be whole, Jung said, both must be integrated.) The boy-man is pure animus – animosity – shorn of anything that might be considered anima – the animating effects of emotion, creativity, compassion, collaboration.

Adler called this the “masculine protest” and regarded it as an evil force in history, underlying, for instance, the rise in fascism in the 20th century. To be taken seriously as a leader one must appear devoutly unempathetic, unfeeling, uncompromising, unflinching. When men get together – in locker rooms, strip clubs, prison movies – often a kind of competitive manliness ensues. The boys trip degenerates into a PG-version of “Fight Club”. The most macho are the most afraid.

One year, when The Open was at Royal Lytham, I went with some other male sportswriters to the nearby seaside resort town of Blackpool, home to the biggest roller coaster in the United Kingdom. We queued, paid our money and were subsequently lurched, plunged and whizzed around the terrifying track. “That was awful,” one of us said as we disembarked, jelly-legged. “I know,” said another. We realised that none of us had wanted to go on the infernal coaster, but no one had wanted to be the first to bail. No one was man enough to say no.

Hogan’s masculine protest was a silent howl. His detachment and withdrawal are understandable. Less understandable is how these qualities have become a desirable part of the blueprint of manhood. Men are three times more likely than women to have an addiction and take their own life, and their average lifespan is five years shorter than that of women.

Golf’s lessons are mostly good ones. But it can also teach boys a certain kind of boring, conservative conformity based on restraint, intolerance of difference, reserve in personal relations. Golfers are lone rangers in matching khaki pants.

We tell our sons to man up. There’s no crying in sports, or anywhere else. Boys are raised to feel nothing (except anger, which is manly); to say little; to be expendable cogs in a loveless machine. We create numb, inarticulate loners: John Wayne, Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood. Travis Bickle, Timothy McVeigh, Ted Kaczynski. The guy who works in IT. We create absent fathers. We ride off into the sunset.

Many men who have done everything they were supposed to do wind up on the therapist’s couch in midlife because they feel like dead men walking. Success stories on paper, in person they are ghosts. Cupid’s arrow passes right through.

It was the night before Valentine’s Day that Chester Hogan took his own life. He shot himself in the heart.

John Barton is a London-based counsellor and psychotherapist. He spent many years as an editor for

Golf Digest.