Editor’s Note: To revisit the 2016 U.S. Ryder Cup team is to reflect on a much simpler time in golf. The U.S. hadn’t beaten Europe in eight years, and was four years removed from a humiliating collapse at Medinah. Tiger Woods was recovering from back injuries but still an imposing presence to players as a vice captain. The American team was a disparate group of players with varying degrees of experience, but they all wanted the same thing, to succeed on the PGA Tour, and win back the Ryder Cup. Seven years later, factoring in the unprecedented challenges of a pandemic and an insurgent golf league, it all seems rather quaint, adding a bittersweet layer to this retrospective by John Feinstein.

Matt Kuchar was the court jester of the 2016 U.S. Ryder Cup team, though most golf fans never would have known that.

“His image with the public is a hundred percent different than who he really is,” says Zach Johnson, a close friend. “He smiles and says all the right things, and then you get behind closed doors, and he’s the devil.”

Johnson meant that in an endearing way. He was a frequent victim of Kuchar’s plots, often opening his locker to find some kind of poster—sometimes of a man, sometimes of a woman, usually without any clothes on—hanging prominently from the door. Kuchar’s hope was that Johnson might open his locker in the presence of a media member or perhaps a pro-am partner and be forced to explain himself.

Johnson’s explanation was always quite simple: Kuchar.

Kuchar has a wide, ever-present smile, one that earned him the nickname Smilin’ Matt, and has long been a fan favorite because of that smile and his easygoing manner. Beneath it, though, Kuchar is not only a nonstop prankster, he’s one of the brighter, more thoughtful people in the game.

Phil Mickelson, wary of Kuchar’s antics, tries to avoid verbal combat with him. “He’s too quick,” Mickelson says. “I’m good. I’m very good. But I never beat him.”

Several years earlier, Mickelson had showed up at a tournament wearing custom-made alligator shoes that were a shade of Augusta National green. He walked onto the range and began loosening up. Kuchar was right next to him.

“What are those?” Kuchar asked, pointing at the shoes.

“These?” Mickelson answered. “These are shoes you can only get after you’ve won three Masters.”

Mickelson grinned. He’d played his trump card.

“Well, if that’s the case,” Kuchar said, turning away to resume his warm-up, “I hope I win only two.”

‘SOMETHING SPECIAL’

Kuchar and Mickelson teamed up in Saturday afternoon’s four-balls at Hazeltine to defeat Sergio Garcia and Martin Kaymer, helping the U.S. team take a 9½-6½ lead entering Sunday’s singles. After the day’s play had ended, Kuchar announced to his captains and teammates that he had “something special planned for tonight” once they were back at the hotel. Everyone was convinced this was another Kuchar prank. U.S. captain Davis Love III had planned a relatively informal evening that would include a lot of non-team members.

“Once you’re back at the hotel, you kind of come out of the zone,” he told his team. “Which is a good thing. You can’t sit around all night thinking about what may or may not happen the next day. It’ll wear you out.”

Mike Eruzione, the captain of the 1980 Miracle on Ice U.S. Olympic hockey team at Lake Placid, would be there. Darius Rucker, a huge golf fan whom all the players knew, would sing a few songs. The ex-captains would be around, and, as always, the wives/partners and caddies would be in the room.

No one was completely certain just how serious Kuchar was about his plan.

“I’m not sure we wanted to know,” Johnson says, laughing.

Love had encouraged the various celebrities and ex-captains to make themselves at home in the team room during the week. “I wanted things to happen spontaneously,” he said. “I didn’t want it to be like, ‘OK, at 8 o’clock on Thursday, Jack Nicklaus is going to speak.’ “

Eruzione brought hockey jerseys for all the players to the team room Saturday night. They had USA on the front and the players’ names on the back. Then he spoke about the importance of understanding the moment, reminding the players what U.S. coach Herb Brooks had told his team before it played the Soviet Union in the most important hockey game ever played, on Feb. 22, 1980: “You were all born for this moment.”

Rucker got up and told the players how much their friendship meant to him. “I want you to know,” he said, “that anytime any of you need me to come and play in one of your charity events, I’m there. Anytime, anyplace. I’ll play golf, I’ll play music, whatever you want or need.” He paused. “But if you lose tomorrow, I’m charging you full price.”

Then it was Zach Johnson’s turn. He passed out shirts that said simply: MAKE TIGER GREAT AGAIN. He had spotted them online a few weeks earlier and bought them for everyone on the team. Every player and vice captain put one on. Love had told Woods earlier in the week that there would come a moment for him to talk to the team—but that it shouldn’t be forced.

“It’ll just happen,” he said. “You’ll know when it’s time.”

With everyone in the room yelling “Speech!” Woods knew it was time. He told the players how much it had meant to him to be part of the team as a vice captain, how much he had enjoyed everything that had gone into the week, and how close he now felt to each of them.

“It was a cool thing,” Mickelson said later. “I think Tiger had been heading in the direction of being one of the guys for a while, but the week at Hazeltine really put it over the top. … He’s not the same guy he was all those years ago, when everything he’d been taught by his dad said, ‘Don’t give any of your secrets away.’ Now he’s willing to share pretty much anything he thinks will help us win.”

Earlier in the week, in a car going from the golf course to the hotel, Mickelson and Woods had engaged in the sort of good-natured grief-giving exchange no one had ever dreamed they would witness.

“Can’t wait to see you back on tour,” Mickelson said at one point. “I just hope you can find the planet off the tee again sometime soon.”

“Found it enough to win 14 and 79, didn’t I?” Woods answered, referring to his haul of major victories and PGA Tour wins.

Mickelson also had a gift to give to his teammates: dog tags. Each had the player’s name on it and the word Beginning. Mickelson had always maintained that Hazeltine would be the beginning of a new era for the U.S. Ryder Cup team. He wanted to give the other players one more reminder of that.

“HALF THE ROOM—AT LEAST—WAS CRYING”

Finally, after the celebrity speeches and the gift-giving, it was Kuchar’s turn. The idea for the presentation had come to Kuchar after a birthday dinner he had attended eight years earlier at the home of Seth Waugh, the former CEO of Deutsche Bank, a longtime PGA Tour sponsor. “He just said, ‘OK, this is a family tradition,’ and started going around the room,” Kuchar remembered. “It really made you think. It was actually pretty cool.” Kuchar had made the idea a part of his Thanksgiving family dinner. Now he wanted it to be part of Saturday night at the Ryder Cup.

He brought in a white board and placed it in front of the room. He stood before his teammates with none of the usual Kuchar “gotcha” in his voice or his demeanor.

“I want each of you to tell me two things in your life that you’re really grateful for,” he said. “You aren’t allowed to say friends, family or health. We’re all grateful for those things, and we all understand how important they are. I want other things. I want things you’re thinking about right now sitting in this room tonight.” It took a moment for everyone in the room to realize Kuchar was serious. If there was any doubt, he proved it by starting.

“I talked about how much I loved golf and how grateful I was I could play golf for a living,” he said. “I’d also thought about something Phil had said at the Presidents Cup in Korea. He talked about how cool it was that the captains and vice captains thought enough of him to make him a captain’s pick even though he hadn’t made the team on points. That resonated with me—especially after Davis made me a captain’s pick.”

Bubba Watson talked at length about why it was so important for him to be part of the team as a vice captain after not getting picked and went on emotionally about how much it meant to him that his father had lived long enough to see him play in the Ryder Cup in 2010.

“I think it made all of us stop and realize how lucky we were to be sitting there getting ready to try to win the Ryder Cup the next day,” Brandt Snedeker says. “It was really pretty cool.”

Snedeker followed Watson. He began by thanking him for all the input and support he’d given him all week. Then he talked about how fortunate he felt to be in this moment and how important it was to him to make sure not to let anyone down the next day: Love, Mickelson, the other players and captains, including past captains.

Then Snedeker pulled out his phone. A hockey fan, he had read a book a few years earlier by Mike Babcock about coaching the Canadian Olympic team in 2010 under nearly unbearable pressure because the Games were in Vancouver.

The book was called Leave No Doubt: A Credo for Chasing Your Dreams, and in it, Babcock had referenced a quote his coaching mentor, Scotty Bowman, had passed on to him. It came from Chuck Swindoll, a pastor/radio talk-show host. “I keep it in my phone,” Snedeker explained, “because it helps me to pull it out and read it again when I really feel like I’m under pressure.”

He began to read: ” ‘The longer I live, the more I realize the impact of attitude on life. Attitude, to me, is more important than facts. It is more important than the past, than education, than money, than circumstances, than successes, than what other people think or say or do. It will make or break a company, a church, a home.’ “

Here, Snedeker added three of his own words: “or a team.”

“That’s when I started to lose it,” he said later. He tried to continue that night. “‘The remarkable thing is, we have a choice every day regarding the attitude we will embrace for that day. We cannot change our past. … We cannot change the fact that people will act in a certain way.’ “

By now, Snedeker had lost it completely. He handed the phone to his wife, Mandy, and she finished for him.

” ‘We cannot change the inevitable. The only thing we can do is play on the one string we have, and that is our attitude. I am convinced that life is 10 percent what happens to me and 90 percent how I react to it. And so it is with you. … We are in charge of our attitudes.’ “

Mandy’s voice was quavering at the finish, but she got through it.

Photo by Scott Halleran/Getty Images

By now, many in the room were crying. Steve Stricker was next. He was already crying when he stood up. He said about four words and broke down completely.

“Because that’s what I do,” Stricker said later, laughing. “By the time they got to me, half the room—at least—was crying. I got up, started to talk, and lost it. Not only am I not sure what I said, I’m not sure anyone understood what I said. But the whole thing was great.”

“Instead of feeling the pressure that we knew was coming the next day, we all felt great,” says Zach Johnson. “I think that’s exactly what Kooch was going for.”

Kuchar stood at the board throughout, writing down what each person was thankful for until he’d filled several pages. At one point, Nicklaus poked his head in the door, saw what was going on and said, “Just keep doing what you’re doing—in here and on the golf course.”

TIGER GIVES REED A SURPRISE

Sunday morning, Patrick Reed was more nervous than he had ever been. He was, after all, Captain America, and in that role it was his job to slay Captain Europe—Rory McIlroy—in the opening match.

“I was tight on the range,” Reed said.

“Really tight. I didn’t like the way I was hitting the ball, and I knew it was nerves. I was telling myself to calm down and just get ready to play, but it wasn’t working.”

Woods was on the range, watching Reed and Jordan Spieth—whom he had taken to describing as “my guys” because they had been in his pod all week—warm up. He could see that Reed wasn’t quite himself. “Hey, Patrick,” he said. “Come here a minute.”

“I thought sure he was going to give me a pep talk, say something about my swing or about just relaxing and not trying too hard,” Reed says. “I walked over there. He had his arms folded. I waited. He looked really serious.

“And then he told me a dirty joke.”

Woods is well-known among the players for telling and enjoying dirty jokes. So-called locker-room humor is not limited to male athletes. One of the all-time-best dirty-joke tellers among the jock set was Chris Evert, the girl-next-door tennis immortal. No one looked more demure or proper than Evert. No one loved a good down-and-dirty joke more than she did.

When Woods told Reed the joke, his face never changing expression, Reed broke up.

“It was actually the perfect thing to do,” Reed said later. “It just broke the tension. I went back to hitting balls, and all of a sudden I was loose as could be. I was ready.”

Reed and McIlroy went on to play one of the most emotional matches in Ryder Cup history. McIlroy made four straight birdies on 5 through 8 … and lost ground. “How great is this?” McIlroy said at one point.

Photo by Andrew Redington /Getty Images

“I mean, how great is this?” Added Reed after he’d prevailed, 1 up, before a raucous crowd: “No way could you hear anything.”

The best-played match of the day for all 18 holes, however, was Mickelson versus Garcia. Although there was plenty of very public negative history in the Garcia-Woods relationship, Sergio and Mickelson weren’t buddies, either. Their match was played with very little talk or “nice shots” between them, even though there were plenty of nice shots.

Mickelson and Garcia made 19 birdies between them: 10 by Mickelson and nine by Garcia. Mickelson made the only bogey, three-putting the par-5 11th. Remarkably, Mickelson shot 63 while playing the four par 5s in even par. With the match tied, both men birdied the last two holes, Mickelson rolling in a 22-footer on 18 and Garcia halving the match with a 15-footer.

The only question left was who would have the honor of clinching the Cup. Lee Westwood had to hole his bunker shot for a birdie and hope Ryan Moore missed his putt, or the Ryder Cup would be over.

Westwood didn’t come close. The Ryder Cup was coming back to the United States.

“PHIL LOOKED PRETTY BEAT UP”

Both teams partied until close to dawn on Monday. There was, to say the least, a lot of drinking in both team rooms. At one point, Mickelson and Dustin Johnson got into an argument about whether Phil could get out of a DJ headlock.

“No chance, dude,” Johnson said, finding the notion almost laughable.

“Let’s find out,” Mickelson insisted.

Everyone gathered around, and Mickelson tried to get loose. No luck.

He insisted on trying again. No luck. Then, again. Same result.

“By the time it was over,” Stricker said, “Phil looked pretty beat up. He had no shot.”

That didn’t deter Mickelson. He kept insisting that this time he’d get loose.

“What can I tell you?” Mickelson said later. “I thought I could do it.”

He couldn’t.

EUROPE JOINS THE PARTY

It was closing in on 11 o’clock when Rory McIlroy suggested to European captain Darren Clarke that it was time to go and pay tribute to the winners.

Clarke and McIlroy led the way across the lobby to where the Americans were partying. When they walked in, Clarke found Love and said, “Your team room is a lot nicer than ours.”

“Home-court advantage,” Love said.

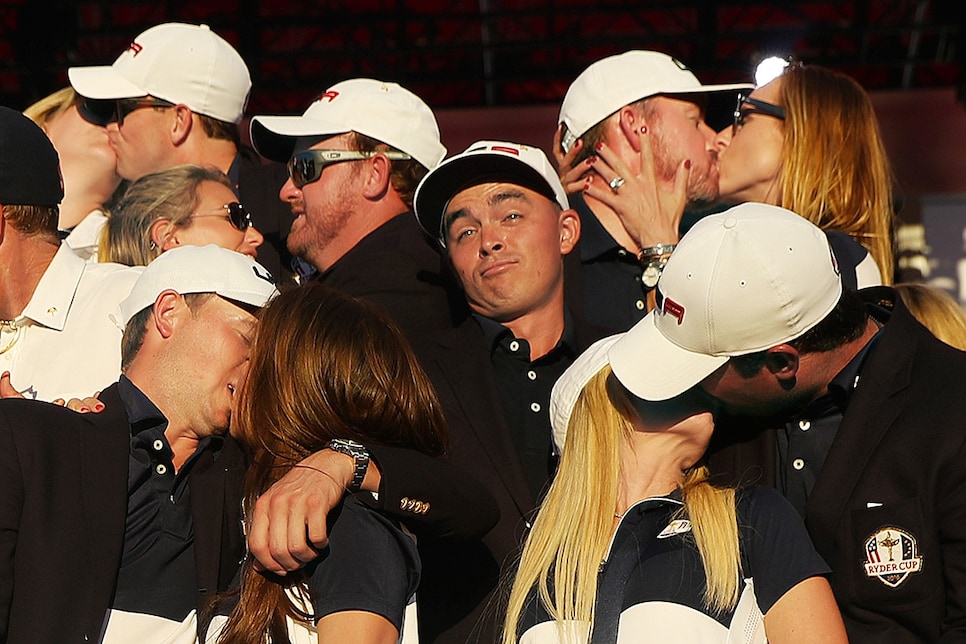

The first thing McIlroy noticed was what Love was wearing: a onesie that said USA on it. Rickie Fowler had brought a number of onesies for himself and the USA ones for the rest of the team. In victory—fueled by the alcohol—Love had agreed to wear one.

The second thing McIlroy noticed was the T-shirt Snedeker was wearing. “We’d all been given shirts at the beginning of the week that said Beat Europe on them,” Snedeker says. “When we got back to the hotel, I took mine, found a Sharpie, and wrote WE on top of the Beat Europe. Then I put it on.”

When McIlroy saw the T-shirt, he reached into his pocket for a Sharpie of his own—golfers almost always carry a Sharpie to be prepared to sign autographs—walked over to Snedeker, and, under the WE Beat Europe, wrote, For the first time in a decade!

European vice captain Ian Poulter was right behind him. He turned Snedeker around, and on the back of the shirt wrote, I didn’t hit a f—— shot!

“I promise you that T-shirt is in a safe place,” Snedeker says.

Someone found a microphone, and Clarke told everyone in the room what a great week it had been and how honored he had been to lead Europe and to compete with the Americans. Then everyone broke into small groups, and the toasts and the alcohol flowed.

“I’m sure I had a great time,” Westwood says, “but I don’t remember much about it.”

McIlroy found Woods near the bar, and the two began to give each other putting lessons. Stricker and vice captain Jim Furyk stood watching.

“There was such a feeling of pride,” Stricker says. “I’ve always been bothered by the fact that people said we didn’t get along in the team room in the past, and Europe did, and that’s why they won. I never felt that way. But the younger guys on this team were really friends—close friends. You could see that even before we got to Hazeltine, and it was such an important part of the week.”

Woods and McIlroy gave up on trying to teach each other how to putt, and McIlroy found himself at the bar drinking shots with Sybi Kuchar.

“I lost, as best I can remember,” McIlroy says. “The girl can drink.”

Matt Kuchar, watching his wife and McIlroy, had his Kuchar grin firmly in place. “It was just nice to see Sybi so relaxed and to see the camaraderie between the two teams,” he says. “I was loving it.”

Photo by Scott Halleran/Getty Images

Midnight came and went. On one side of the patio, Snedeker, Spieth, Woods, Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka and Notah Begay were smoking victory cigars.

“It was kind of funny to see Jordan smoking a cigar,” Snedeker says.

At the other end of the patio, Mickelson, Clarke and Love sat, drinks in hand, reliving past Ryder Cups. As Love listened to Mickelson and Clarke, he couldn’t help but enjoy the moment.

“That might have been the highlight of the whole week for me,” Love said. “Look, I’m a little corny sometimes, but I sat there listening to the two of them, and I honestly thought to myself, This is what Sam Ryder had in mind all those years ago, a competition where the two teams fight like crazy to win and, when it’s over, they go raise a pint to one another and share the experience.”

“I don’t think there are two men I respect more than I respect Davis and Phil,” Clarke says. “They’re very different, but all three of us share a lot in common. I remember at Medinah, when we got word the American players just couldn’t deal with seeing all of us that night, we all understood completely. Then I looked up, and there was Davis, coming to the room because he felt, as the captain, he had to come in and congratulate us. He’s such a class act—in victory, in defeat—all the time. Of all the people I’ve known, no one has ever put others ahead of himself more than Davis.

“He stood up and talked to all of us briefly that night—which is what inspired me to do the same at Hazeltine,” Clarke says. “When he was finished [on that Sunday night at Medinah], I walked over to him, put my arm around him and said, ‘What the hell were you thinking today with that lineup?’ He looked at me for a second, and then he realized I was joking, and he started to laugh. That’s what I wanted that night—to see him laugh. I knew how devastated he was. I wanted to try to lighten the load a little bit.”

Now, four years later, they all laughed well into the night.

This article was originally published on golfdigest.com